By Kelly D’Ambrosio, Digital Archivist, Orange County Regional History Center

During the mid-1990s, Wiccan classes and workshops were regularly advertised in the faith section of the Brevard County newspaper, Florida Today. Interest in the religion was typically demonstrated by news outlets during October, but Brevard was home to local groups that were not just inspiration for novelty Halloween feature stories. One of these groups, Melbourne’s Church of Iron Oak, gained political presence that ignited discussions on discrimination and a movement that created the biannual Florida Pagan Gathering festivals.

The Church of Iron Oak was started by a married couple, John Roger Coleman Jr. and Jacque Zaleski, who were the church’s High Priest and High Priestess. It became a legally recognized church in 1992 through affiliation with the Aquarian Tabernacle Church. Workshops, classes, and many other church services were situated in Melbourne, but six ceremonies throughout the year also took place in the backyard of the couple’s home in Palm Bay. These ceremonies became the catalyst for constant publicity, harassment, religious discourse, and three years of legal turmoil.

Cover page, “The Voice of the Anvil,” Sept. 1993, courtesy of the Graduate Theological Union

A question of zoning?

In March 1994, Coleman and Zaleski received a noise complaint as well as a warning from the city of Palm Bay that they were in violation of zoning ordinances. The city, through a petition started by a neighbor, maintained that the couple were using their house as a church on land that was zoned only for residential uses. The same neighbor had previously called the police, claiming there were disturbing noises and stereotypical satanic activities at the home, but the police had found nothing amiss.

To remedy the zoning violation, Coleman and Zaleski were told to obtain a permit that would allow them an exemption to conduct church services at their house. They also needed to meet building and parking criteria to be considered a proper church. Without a permit, holding a service at the house would bring a fine of $500.

In many ways, differences in interpretation of the word “church” created more problems. While Iron Oak saw a “church” as meaning the congregation itself, the interpretation of a church for zoning meant a place for the congregation. One piece of the story, repeated throughout the next few years in different ways, was that Coleman and Zaleski were told they could not have more than five people at their house for worship or religious services. The congregation at the time was in the 30s, and, understandably, ceremonies included all who could come.

News stories about the issue gained Iron Oak support from the Christian community because ministers in Brevard County admitted to having bible studies, home blessings, and other church gatherings in residences that drew many more than the five-person limit. They rallied around Iron Oak, despite some blatantly detesting the Wiccan religion. They saw the violation as an attack on religion as a whole and said the ordinance opposed the Constitution and encroached on religious freedom. Multiple letters to the editor and guest columns in Florida Today expressed fears about how far the restrictions could go or made fun of the city for what was seen to be a ridiculous rule.

Coleman and Zaleski, believing they were doing nothing wrong, celebrated Beltane at their house in May, knowing a fine would follow. A hearing was scheduled with the Code Enforcement Board of Palm Bay in July and was later cancelled by the city for the vague reason that no other violations had occurred since the one in May. On August 6, Iron Oak celebrated Lughnasadh at the couple’s house, which brought another citation, and a hearing was set for October 12.

This hearing continued on October 31 and November 21 before a verdict was given. During the hearing, Christian leaders supported Iron Oak through testimony, and neighbors made claims on both sides. At the end, the Code Enforcement Board’s verdict concluded the couple had not violated zoning ordinances, because their residentially zoned house was primarily being used as a residence, not a church. Although this was a victory, the battle was not over.

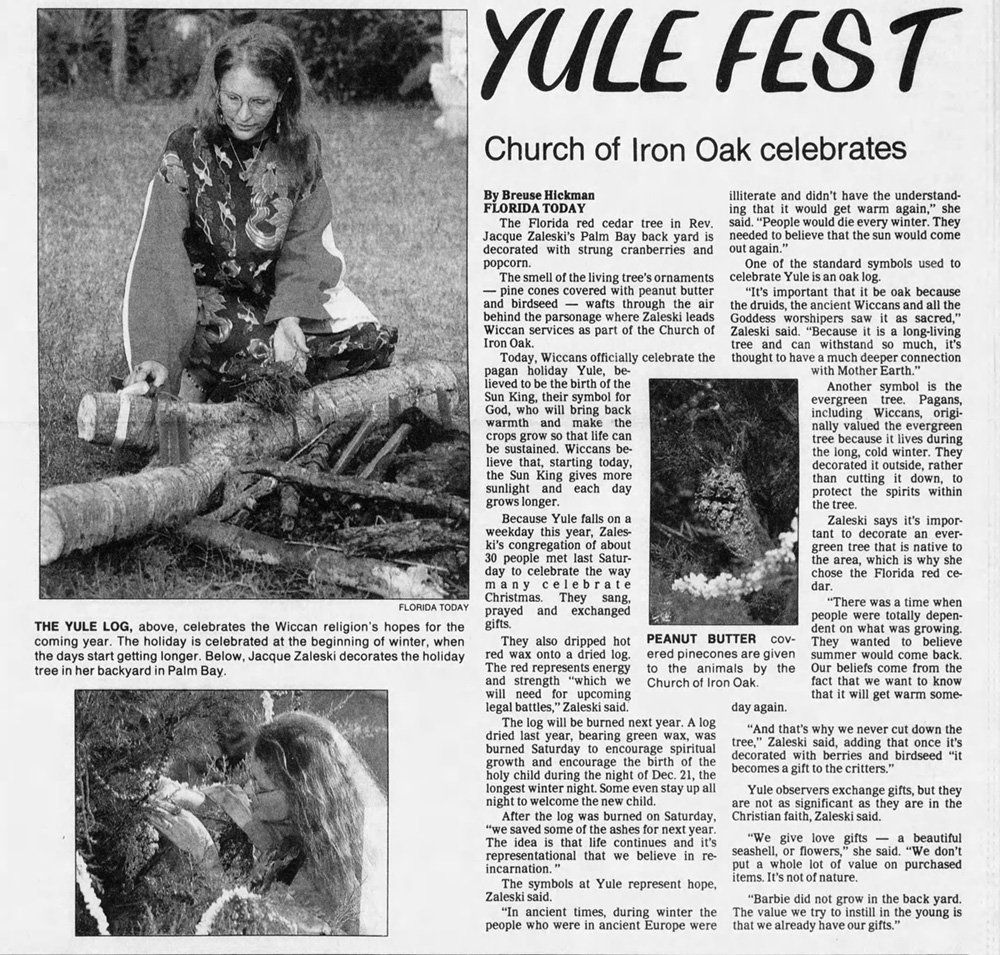

Source: Florida Today, December 21, 1994

A federal lawsuit

While waiting for the October date, the couple had filed a federal lawsuit against the city, which District Judge Ann Conway put on hold until after the Code Enforcement hearing. The lawsuit was first scheduled to be heard in court in December 1995 and later moved to June 1996. The couple used Title 42 Section 1983 of the United States Code and the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act to claim that Palm Bay’s citations both violated their civil rights and greatly hindered their ability to practice their religion.

Some arguments in this lawsuit circled back to the fact that none of the other churches in the area had received citations for conducting religious services at the homes of the leaders or members. This, and the simple verdict from the Code Enforcement Board, made it easy to believe the real issue was not about zoning. One neighbor continued making reports about activities at the couple’s home, and a local conservative group began to blame and harass Iron Oak for the existence of an abortion clinic in Melbourne.

The church’s membership declined during the hearings because publicity around the situation caused fear of and actual retaliation. Another issue arose when Zaleski was asked to give an invocation at a Titusville City Council meeting as part of a program to include other religions into its normally Christian invocations. This resulted in a heavy protest from some of the Christian churches in Titusville on the night of the meeting and caused the City Council member who initiated the program to resign.

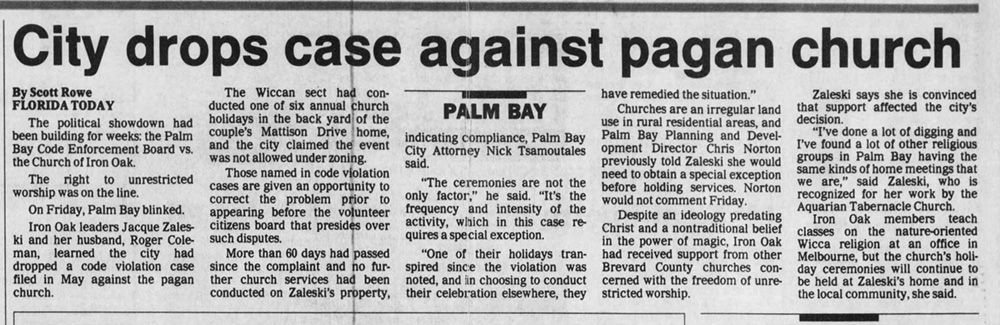

Source: Florida Today, July 11 , 1994

Loss in court, gains in support

Ultimately, Judge Conway saw the Code Enforcement decision that Iron Oak had not violated zoning rules as a sign that the church was not being targeted, and Coleman and Zaleski lost the case. Because the lawsuit was against the city, it didn’t apply to discrimination by private citizens. The church tried to make an appeal but was denied in March 1997.

What came of this was an incredible web of support. While work on the federal lawsuit was ongoing, a Church of Iron Oak Defense Fund was started to help the couple pay for their legal fees. Zaleski participated in interviews, seminars, and Florida Today guest columns, as well as writing the church’s newsletter, The Voice of the Anvil. Coleman spread the story of Iron Oak’s struggle on the internet, gaining an international audience and developing stronger kinship ties. In and outside of the Wiccan community, Iron Oak acquired free legal advice and donations while also hosting fundraising events. On its website, the church sold CDs of Pagan music and a T-shirt created by a Pagan artist to support its cause. For June and October of 1995, Iron Oak planned Solstice and Samhain Freedom Festivals as fundraisers. These events were renamed the Florida Pagan Festival in 1997 and continue on today as biannual celebrations for Beltane and Samhain.

Although the Church of Iron Oak lost the federal case, the attention allowed others to learn more about the Wiccan religion, the multifaceted characteristics of people in that religion, and the complicated natures of support and discrimination. One Baptist minister fought alongside the church for what he saw as a fight for religious freedom; another led the protest against Zaleski’s invocation in Titusville. While many Pagans came to the aid of Iron Oak with tales of their own discrimination, the Wiccan Religious Cooperative of Florida felt that the initial situation was not religious and stayed out of it. All in all, the Church of Iron Oak’s battle in the 1990s constitutes a fascinating story of the complex intersections of law, religion, and humanity.