By Adam Ware from the Spring 2017 Edition of Reflections Magazine

The phrase “baseball innovations” may call to mind new designs for cleats or bats, but one of the most important innovations in baseball history changed not the technologies used to play but the locations where players prepared for a new season.

For many Floridians, spring-training baseball is as natural as the taste of an orange, and both experiences link to major themes in the state’s past – and to big business, too. As the earliest baseball innovators discovered, changing where a team practiced in the spring could determine how teammates played later that summer, and that evolution emerged hand in hand with key stories in the history of the sport, and of our state.

A Rough Start for a Rough Sport

Early on, baseball hardly resembled the nostalgic, genteel game fit for entertaining families gathered for an afternoon at a ballpark. In contrast, the early sport emblematized the rough-and-tumble culture of young manhood that followed the Civil War. Games in the 1860s and 1870s often included broken bones and other injuries numbed somewhat by the state of general inebriation many players inhabited. In keeping with the sport’s general shadiness, the first true instance of spring training appears to have been the New York Mutuals’ 1869 trip to New Orleans, organized by notorious Tammany Hall political leader William “Boss” Tweed.

Rumors persist that the Mutuals’ trip was merely a thinly veiled attempt to cash in on the Radical Reconstruction economy of the coastal South. Tweed presented the idea to the New York City Council, asserting that warm-weather training would offer the team an edge, and the Council responded by offering $9,000 for one trip to the Big Easy (a sum worth more than $157,000 today), but no expense ledgers were kept and no reports were filed.

Despite that massive investment, the Mutuals lost more games during the 1869 season than in any previous season since the club’s 1857 formation. The following year, New Orleans hosted both the Chicago White Stockings and the Cincinnati Red Stockings, whose exhibition games represent the earliest spring-training games as we know them today.

By the mid-1880s, Savannah and Charleston hosted squads but, despite a failed attempt to lure the Philadelphia Quakers, no teams had yet arrived in Florida. In 1885, however, legendary player-manager Cap Anson took his Chicago White Stockings to Hot Springs, Arkansas. Club owner Albert Spalding supported the innovation of using the healthful springs to dry out his players, telling a Chicago reporter that Anson planned to “boil out all the alcoholic microbes” that had “impregnated the systems of these men during the winter.” If the hot springs didn’t work, “I’ll send them to Paris next year and have them inoculated by Pasteur,” Spalding said.

Although Anson was not the first manager to send his teams on spring-training trips, he was the first to succeed at using spring training as a game-winning innovation: the White Stockings won two consecutive championships in 1885 and 1886. Anson was also responsible for another change that affected how Floridians experienced baseball. His popularity, combined with his unwillingness to play with African Americans, helped erect the same “color barrier” that Jackie Robinson later dismantled.

Spring Training Tries Out the Sunshine State

In 1888, the Washington Capitals traveled South on newly reliable railroads to become Florida’s first spring-training team. The trip from Washington, D.C., to Jacksonville took two days, and the small train kept players double-bunked.

The early sport’s rough-and-tumble nature was still in full swing. “When we arrived in Jacksonville, four of our fourteen players were reasonably sober. The rest were totally drunk,” the Capitals’ catcher (and grandfather to a future U.S. senator) Connie Mack told reporters after the team returned to Washington. “There was a fight every night, and the boys broke up a lot of furniture. We played exhibition games by day and drank much of the night.”

Like the Mutuals’ New Orleans trip 19 years before, the Capitals’ Jacksonville visit produced no good results. Complicating matters, north Florida proved generally inhospitable even to sober players, because of the enmity spawned by the Civil War: many early baseball players and teams emerged from the North and the Midwest, leaving Southern sympathizers wary.

Fifteen years later, when Mack returned to Florida as manager of the American League champion Philadelphia Athletics, he blamed the disappointing 1903 season on Florida’s tropical seductions. According to the St. Petersburg Museum of History, Mack’s star pitcher, Rube Waddell, dabbled in live-alligator wrestling and attempted suicide following a failed fling with a Jacksonville brunette. Another decade would pass before any baseball team returned to Florida.

The Dawn of the Grapefruit League

With reliable rail travel and emergent automobiles and airplanes, the distance between sunny Florida and baseball’s best teams shrank almost yearly in the early 20th century. With the Cubs in Tampa, the St. Louis Browns in St. Pete, the St. Louis Cardinals in St. Augustine, and the Athletics returning to Jacksonville, the 1914 spring-training season brought the first makings of a playable league to the state. Beyond the sun and the security of modern travel, Florida’s communities began offering more enticements to persuade major-league teams to build relationships in Central Florida.

Between 1910 and 1929, Orlando’s population quadrupled, signifying a full recovery from the 1894-1895 freeze. That growth represented a population boom statewide, and many cities’ strategic plans involved building baseball stadiums to court teams seeking wintertime homes.

In 1914, prominent St. Petersburger Al Lang allegedly paid all costs for the St. Louis Browns to come to his “Sunshine City,” including the expenses of Missouri reporters covering the team. When the Browns arrived, they discovered the first truly dedicated spring-training facility: the 4,000-seat Sunshine Park, which was packed to capacity for the Browns’ first game against the Cubs. Mack’s Phillies replaced the Browns at Sunshine Park the following year, and after the Phillies won 14 of their first 15 games in the 1915 season, the permanence of a wintertime Florida home for American baseball was secure.

That same season, aviation pioneer Ruth Law made a practice of dropping golf balls out of an airplane as an advertising gimmick for a Daytona Beach golf course. At that time, the Brooklyn Dodgers called Daytona Beach home, and manager Wilbert Robinson suggested Law throw a baseball from her plane to promote their games, offering to catch the baseball as part of the act. As she approached the stadium, Law realized she had left the baseball in the hangar, but happened to have a grapefruit in the cockpit. She threw it to Robinson instead, but as he grasped at it, it exploded in his face. With that, the Grapefruit League was born.

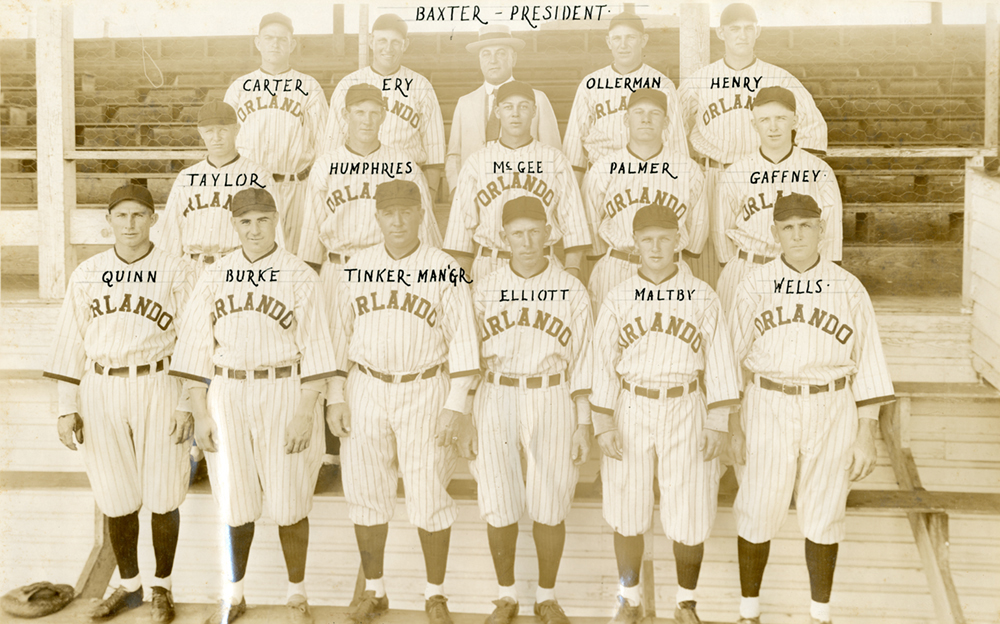

Joe Tinker and His Orlando Field

As baseball fever took hold across the state, Orlando teams – including the Orlando High School Baseball Club – began staging games, and as early as 1914, those games took place just off the 200 block of Tampa Avenue. By 1920, Orlando’s own minor-league team, the Florida State League’s Orlando Caps, had taken the field as its home.

In December, baseball legend Joe Tinker moved to Orlando and took a position managing the Caps, which in 1921 became the Orlando Tigers. Before bringing his managerial skills to Orlando, Tinker himself authored one of baseball’s great innovations: as the Chicago Cubs’ shortstop between 1902 and 1912, Tinker popularized the double play as the most exciting or disastrous act in defensive baseball – depending on the team for which a fan cheers, of course. Alongside second baseman Johnny Evers and first baseman Frank Chance, Tinker became immortalized in Franklin Pierce Adams’ poem “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon,” which describes the experience of a New York Giants fan watching the Cubs’ stars at their best:

These are the saddest of possible words:

‘Tinker to Evers to Chance.’

Trio of bear cubs, and fleeter than birds,

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

Making a Giant hit into a double –

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

‘Tinker to Evers to Chance.’

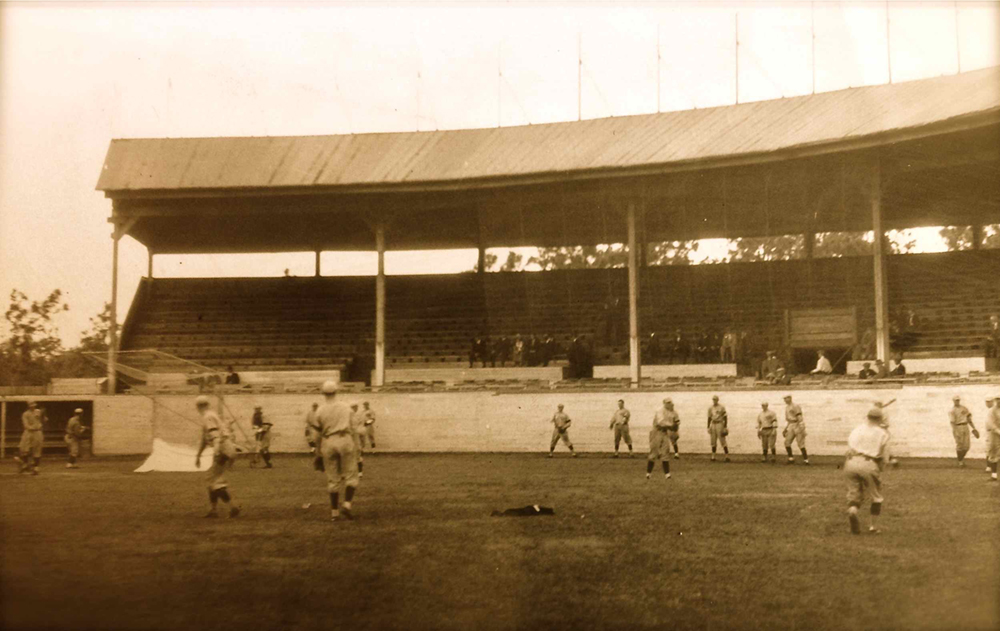

By 1923, Tinker’s Tigers were performing well enough, and his own celebrity had drawn enough popular interest, that Tinker persuaded the Orlando Athletic Association to buy the Tampa Avenue property and to build a stadium at the exorbitant cost of nearly $50,000. The Orlando Morning Sentinel referred to the project as “Tinker’s Field” in an April 1923 article, and the name stuck: Tinker Field was born.

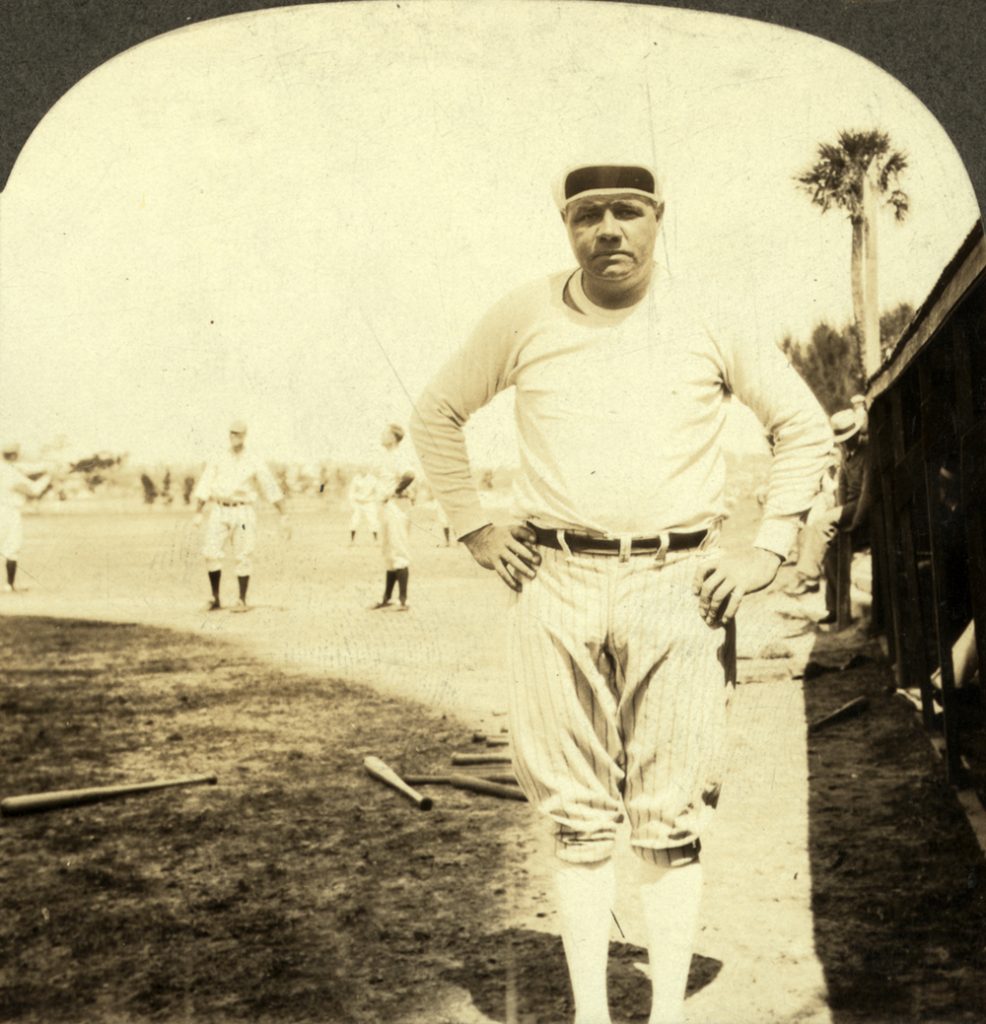

That year, the Cincinnati Reds, for whom Tinker had played and managed, called the field home for spring-training exercises; with the exception of the World War II years – which temporarily seized on materials and manpower needed for the game – Tinker Field played home to spring training for 67 years before finally closing those operations in 1990. In that span, some of the greatest names in baseball history rounded the Tinker Field diamond: Lou Gehrig, Babe Ruth, Jackie Robinson, Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, and Hank Aaron all played either spring-training or minor-league ball in Orlando.

From Lakeland to Leesburg and from Dunedin to Daytona Beach, generations of Central Floridians know our brief winters subside when the days grow a little longer, the nights are a little warmer, and the crack of a ball on a bat splits the afternoon air. Baseball in Florida seems as natural as the sunshine, but its arrival here proved to be both innovative and revolutionary for America’s pastime.