By Lesleyanne Drake from the Spring 2021 Edition of Reflections Magazine

The first modern zoos in the United States opened in the 1870s. Unlike private menageries, modern zoological parks were intended to educate the public about the natural world and also to provide a source of entertainment. Like museums and botanical gardens, zoos became symbols of civic pride as well as regional attractions.

By 1932, there was serious discussion in Orlando about creating a city zoo, which residents believed would attract thousands of families and tourists. Both Sanford and Kissimmee already had successful zoos; why shouldn’t their city have one, too?

By attracting visitors, a zoo would also spur business development for Orlando, supporters maintained. But despite inspiring a passionate grassroots movement, the quest for a zoo in the City Beautiful was fraught with challenges from the beginning.

Radio Nick Leads the Charge

Although the first reported discussions about an Orlando zoo came from the Junior Chamber of Commerce, the most vocal supporter quickly became Delmar “Radio Nick” Nicholson. Born in 1899 to Augustus and Alice Nicholson, he and his four siblings grew up surrounded by animals. Their father was a taxidermist who frequently brought home wild animals, turning the Nicholson household into its own kind of zoo. According to one family story, visiting relatives were surprised to discover an alligator living in the bathtub!

From his father, Delmar Nicholson acquired an appreciation for nature and a lifelong love of animals. Even as he pursued a career in radio engineering, earning the moniker “Radio Nick,” he advocated for wildlife conservation, educated others about Florida animals, and became widely respected as a herpetologist, despite a lack of formal education in the subject. He wrote educational articles, gave wildly popular presentations featuring live snakes, and helped spearhead local conservation initiatives.

In 1933, Nicholson began advocating for a zoo, calling it a “necessity . . . for a city of Orlando’s caliber” (Orlando Sentinel, June 30, 1933). The project couldn’t have had a better spokesperson. Not only was he passionate about animals, but he was also well known and well liked in the community, partly through his business selling and repairing radios. Every Christmas Eve he would fill a large porcelain duck with whiskey and pour drinks for folks on Orange Avenue, wishing them a Merry Christmas. He seemed to know everyone and had a voice that could rally people to a cause.

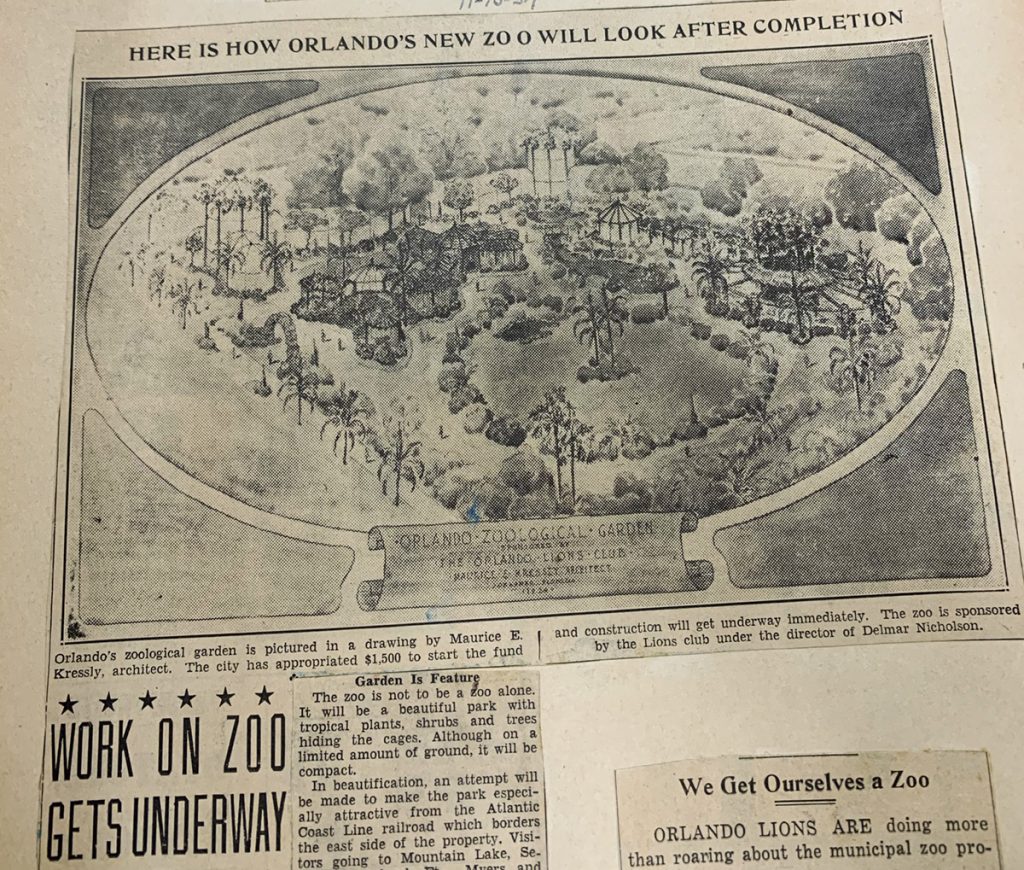

With Nicholson as its champion, it wasn’t long before Orlando’s zoo started to become a reality. In October 1934, the Orlando Lions Club and City Commissioner Jack Sparling agreed to sponsor the project. With their backing, Nicholson presented architect Maurice Kressly’s concept sketch of a “flower-bedecked aviary, monkey house, and lion cage” to the City Council, which designated $1,500 to build it and $1,000 more for ongoing maintenance (Sentinel, Nov. 15, 1934).

Nicholson and others immediately began hosting fundraisers and collecting donations, including construction materials from Orlando business owners. In December 1934, the Lions Club incorporated the Orlando Zoological Society as a nonprofit to manage the zoo, with Nicholson as its curator and president, and Orlandoans from politicians to high schoolers voiced eager anticipation for the opening of the city’s new attraction. However, concerns about the zoo arose as quickly as the outpouring of community support.

So Many Animals, Too Little Time

The first challenge was finding an appropriate location. The proposed site was tiny – about 300 by 290 feet on West Livingston Avenue, between Garland Street and the railroad tracks – and members of the Greater Orlando Chamber of Commerce argued against it before the City Council, proposing a move to the spacious Loch Haven exposition grounds (now Loch Haven Park).

The Livingston location would be “obnoxious” to winter visitors, the Orlando Lawn Bowling Club declared in a news report on Nov. 21, 1934, and Harry P. Leu, whose business was across the street, warned that Orlandoans would undoubtedly be annoyed by insects, animal cries, and foul smells.

In contrast, Nicholson and other advocates envisioned a beautiful park and gardens that could be seen by passengers on the Atlantic Coast Line railroad. If the zoo outgrew its compact home, they would then consider a move. Except for a lion and monkeys, the zoo wouldn’t have exotic animals that needed more space and more money to acquire and maintain, they argued.

Instead, Nicholson was preparing to capture Florida wildlife, including a bear, to fill the zoo even before it was funded, the Sentinel reported. He also planned to collect more than a dozen species of birds at his own expense, as well as deer, otters, and other animals, and both the Sanford and Kissimmee zoos had promised him animals.

Orlando residents also donated creatures they had caught (snakes, alligators, wild hogs, armadillos, birds, bullfrogs, wildcats, foxes, and more), raised (chickens and ducks), or kept as pets until they became too much to handle (monkeys, skunks, and raccoons). “Somebody is always trapping a wildcat or taming a raccoon and, growing tired of them, looking for an avenue of escape,” a Sentinel article noted on Nov. 15, 1934.

One notable example was Sheriff Harry Hand’s pet monkey, which was let loose in the courthouse “to play around” for exercise and bit Hand’s secretary, Ruth Wyrick, on the leg (Sentinel, Sept. 4, 1935). Wyrick’s wound became infected, requiring medical attention, and Hand announced that his pet was destined for the zoo.

By February 1935, so many animals were being offered that Nicholson was running short on cages in the still-under-construction zoo. He housed animals anywhere he could – including in the Violet Dell Florist shop in the San Juan Hotel building and at a local animal hospital. By late 1935, “scores of animals” were temporary residents at the Kissimmee Municipal Zoo while waiting for their new home at the Orlozoo, as some members of the press dubbed it (Sentinel, Sept. 25, 1935).

More Zoo Than the City Can Chew?

The zoo turned out to be more of an undertaking than anyone had anticipated. At first, as donations came flooding in, Nicholson thought it would be ready in a mere 90 days. However, his vision of a modern zoo – with lush grounds, natural-looking enclosures, and an assembly room for classes – cost much more than he initially estimated. By February 1935, just months after getting started, the Zoological Society sought approval to dip into the maintenance funds, with warnings from the City Council that no additional money would be forthcoming.

Even so, Nicholson believed that donations and fundraisers would get the zoo to the finish line. He announced that it would open June 1, 1935, with Dr. Raymond L. Ditmars, curator of the Bronx Zoo in New York City, presiding over the opening ceremony, which would include welcoming a lion into its new home.

Thousands of Orlandoans contributed their time and resources to the zoo – but it was not enough. In May, Nicholdson reported that $18,000 had been spent, including both monetary and material donations, but that $10,000 more was needed. Although dozens of truckloads of rock had been hauled from neighboring counties, he also estimated that 75 more truckloads would be needed to complete the enclosures. Still, he felt sure sufficient funds could be raised and the zoo would open by October 1.

An open house in June drew about 400 people. The turnout reassured Nicholson he was on the way to producing “the finest little zoo in America” (Sentinel, June 17, 1935). Over the next months, the Lions Club divided into teams and competed to bring in donations, staged a circus, and held benefit shows including wrestling and boxing matches, auctions, and special screenings at the Beacham Theater. Meanwhile, the grand opening was postponed another month, to November 3.

Despite the delays, community members were excited about having their own zoo. In September, another preview reportedly drew over 2,000 people. The star of the show was a fawn Nicholson had raised.

The crowds of visitors probably had no idea that work on the project had nearly crept to a halt. Laborers provided by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) at no cost to the Zoological Society were perpetually low on materials. By this time, Nicholson had quit his radio business and was working full time on the zoo. With only a month until the opening, he asked the City Council for an additional $3,000, touching off a storm of conflict that would spell the beginning of the end for Orlozoo.

Trouble in Paradise

Mayor V. W. Estes and the city commissioners, initially supportive of the zoo, were hesitant to commit more funds. Nicholson’s requested $3,000 would not complete the project – more money would have to be raised, and, on top of that, funds would still be needed for ongoing maintenance.

One commissioner cited a laundry list of city projects that needed funding, including more police officers, another garbage truck, street widening and beautification, and welfare programs. Mayor Estes suggested raising taxes. Although Nicholson was firmly against a tax increase, the mere idea seemed to derail negotiations.

Despite public concern over the possibility of higher taxes, the zoo still had many ardent supporters. Orlando Senior High School students wrote that the zoo must be completed “to instill in students of all ages a knowledge, respect and love for all wild life in our state” (Sentinel, Nov. 10, 1935). A winter visitor chastised the city for not having finished the zoo, saying that it was a “disgrace” to leave it looking “like the ruins of Pompeii” (Sentinel, Nov. 2, 1935).

By the end of November, a plan had been reached to eke out another $1,500 from the city through the collection of back taxes. Meanwhile, work on the zoo stopped. The lack of funds for construction materials meant the WPA workers had nothing to do and were forced to leave the zoo unfinished.

In an attempt to inspire support, Nicholson put on a snake show at Tinker Field. Several hundred people watched him lecture about 35 snakes he had captured in Florida swamps as well as how to administer first aid for a snake bite. In the show’s highlight, he extracted venom from a large diamondback rattler and then injected the venom into a king snake to demonstrate its immunity. However, the fact that two live guinea pigs were fed to the rattlers drew criticism, and some even called for a new zoo manager who demonstrated greater compassion for animals.

As soon as negotiations with the city were finalized, Nicholson did resign as the zoo’s curator, because he could no longer afford to volunteer all his time and money. Less than two weeks later, he took a

job as a car salesman at J. C. Milligan Motors. He did promise to continue as president of the Zoological Society.

Enough enclosures were completed to have some animals on display, and the zoo continued to operate, but it never had its grand opening or fulfilled Nicholson’s vision. Still, he returned to run the zoo in June 1936, and it remained a popular attraction throughout the year. A 12-foot alligator lassoed by Mayor Estes and four other men drew record crowds.

The End Is Nigh

Orlozoo struggled through the first half of 1937, but by September, a newspaper report described it as looking “seedy,” with an “air of deterioration, of neglect” (Orlando Evening Star, Sept. 29, 1937). There were few animals, and the enclosures appeared to be falling apart, with weeds, foul water, and debris. In October 1937, the president of the Lions Club appeared before the City Council and stated that the group could no longer operate the zoo.

A months-long argument ensued, but everyone seemed to agree that the zoo had to be either refurbished or demolished. Nicholson, who had once again stepped away from day-to-day management of the zoo, believed that demolishing it would be a deep insult to the hundreds of residents, businesses, and schoolchildren who had donated to the project (more than $19,000 in cash, materials, and labor). He acknowledged that thousands more would be needed to complete and maintain the project.

It did not help that animals kept escaping. A young buck reportedly chased two women down the street before being tackled and returned to its paddock. Later, another buck (or perhaps the same one) jumped through a fence when the Wilson and Toomer Fertilizer company across the street went up in flames. Then two monkeys and a 30-pound raccoon made a jailbreak.

The tipping point came when four monkeys escaped through a rusted hole in the roof of their enclosure. The city’s investigation into the incident threw the zoo’s problems into even sharper relief. Not only were the metal enclosures rusting, but floorboards were deteriorating, and there was a foul odor from excess food left to rot. With funds from the city doled out in “dribbles,” the zoo operated “hand to mouth” (Evening Star, Dec. 22, 1937).

Editorials appeared asking the City Council to save the zoo, and hundreds of schoolchildren participated in a letter-writing campaign. It wasn’t enough. In April 1938, it was decided that rehabilitating the zoo would be too expensive. Instead, the rock would be sold and most of the animals would be “sold or otherwise disposed of” (Evening Star, April 27, 1938). However, the remaining birds and bird enclosures would be maintained as an aviary, with pathways and shrubs added to create a simple park.

The Hidden Story

Little is known about what happened to the animals that lived in the Orlozoo. Some may have been transferred to other zoos, and some released into the wild. The bird enclosures remained as the “City Aviary” into the 1940s, even as the property was leased from the city for a pet shop and then used by the parks department to house plants. According to Eve Bacon’s Orlando: A Centennial History, the remaining birds were transferred to Mead Botanical Gardens at some point before the sale of the property in 1945.

Nicholson went on to a successful career as a salesman and radio store owner. He also served on the Orlando City Council and was a founder of Goodwill Industries of Central Florida. He later bought a small island on Bay Lake, where he raised award-winning orchids, a variety of seedless lime, and other plants. The property would eventually be purchased by Walt Disney World and turned into Treasure Island (later renamed Discovery Island).

Nicholson passed away in 1978, at the age of 79, never having seen his dream of a free public zoo in Orlando come true. Despite his initial idea of having a lion and potentially one or two other exotic animals, he maintained that the primary purpose of the zoo had always been to educate the public about Florida’s native wildlife, a goal that may have been in conflict with others’ desire for the zoo to be an exciting tourist attraction.