By Rachel Williams

Before Gen. Henry Sanford incorporated the Florida town that would bear his name in 1877, significant preparatory work was required. In 1870, Sanford purchased over 12,000 acres of land west of Mellonville, intending to enter the state’s burgeoning citrus industry. He began by clearing the land and planting orange trees, establishing the St. Gertrude Grove west of what is now downtown Sanford and later a new grove named Belair. Residing primarily in Brussels, Belgium, during this period, Sanford enlisted engineers J.N. Whitner and Richard Marks in 1870 to develop the groves and manage the land-clearing operations.

Initially, Whitner and Marks hired local white workers for the clearing and planting tasks. However, they quickly found the work unsatisfactory, leading Marks to write to Sanford that “the native white worker is not worth a dime.” The local workers were dismissed and, feeling resentful, became antagonistic. When Whitner and Marks hired Black contract laborers, the locals threatened both the laborers and Whitner, occasionally resorting to violence, which included firing into their camp and wounding a laborer.

The quest for workers

Faced with these challenges, Sanford sought alternative labor sources. Joseph Wofford Tucker, a local slaughterhouse owner and Sanford’s business partner, suggested employing Chinese laborers, citing their endurance and cost-effectiveness. However, it was not until February 1871 that Dr. Wilhelm Henschen proposed using Swedish labor. Henschen offered to recruit Swedish workers, with his brother Josef assisting in the recruitment process in Uppsala.

The Henschen brothers worked to establish contracts and make travel arrangements for the Swedish workers. During the late 19th century, Sweden experienced significant emigration to the United States due to rapid population growth and declining agricultural viability, which likely motivated many Swedes to seek opportunities abroad. Henschen’s contract promised paid passage to Florida and one year’s living expenses in exchange for a year’s work on Sanford’s groves. This offer attracted many Swedes eager to start a new life in America.

Journey to a new life

Between 25 and 35 Swedes, primarily men, departed from Uppsala with Henschen on April 23, 1871. Their journey took them first to Gothenburg, then by boat to Granton Harbour near Edinburgh, and by rail to Glasgow. From there, they sailed to New York in steerage class on the S.S. Anglia. After reaching New York, they traveled via steamship to Charleston, South Carolina, then to Jacksonville, and finally up the St. Johns River to Mellonville, arriving on May 30, 1871.

Dr. Josef Henschen with an unidentified boy and woman. Photo courtesy of the Sanford Museum.

Upon arrival at Belair, the Swedes met Henry DeForest, Sanford’s cousin and general agent, and Howard Tucker, the labor overseer. Their accommodations were inadequate, with insufficient space and bedding, and they were ill prepared for the Florida climate. The Swedes voiced their complaints through Henschen, who relayed their concerns to Tucker. Recognizing the importance of maintaining the Swedes’ satisfaction to avoid breaches of contract and labor losses, Sanford agreed to improve their living conditions by providing materials for mattresses, clothing, and shoes. The Swedes’ workday began at 5 a.m. and ended at sunset, with breaks for breakfast and lunch, and they worked half-days on Saturdays and rested on Sundays.

By July 1871, dissatisfaction led some Swedes to attempt escape. On July 19, 1871, DeForest informed Sanford that three men had fled to Jacksonville but were subsequently returned. To retain their labor, Sanford offered each worker five acres of land upon completing their year of work.

In November 1871, a second group of approximately 20 Swedish laborers arrived in Mellonville, with improved accommodations awaiting them. These Swedes diversified their work, contributing to a sawmill, building construction for the town, and developing Sanford Avenue. However, they maintained demands for better conditions, such as taking holidays off in line with Swedish customs. Their refusal to work over Christmas led to a partial concession from Sanford, with only six laborers working in exchange for a special meal. Their collective demands continued into 1872, causing DeForest to describe a “decidedly mutinous spirit” among them.

Group of Swedes of the New Upsala settlement. Photo courtesy of the Sanford Museum.

By May 1872, when the first group’s contracts ended, only eight Swedes received land deeds from Sanford. This land, north of the Belair grove, was named New Upsala after their Swedish hometown. Some settlers brought family members to join them in New Upsala. In 1877, Sanford gifted the community a public building, Scandinavian Hall, which served as a meeting place, social hub, and school.

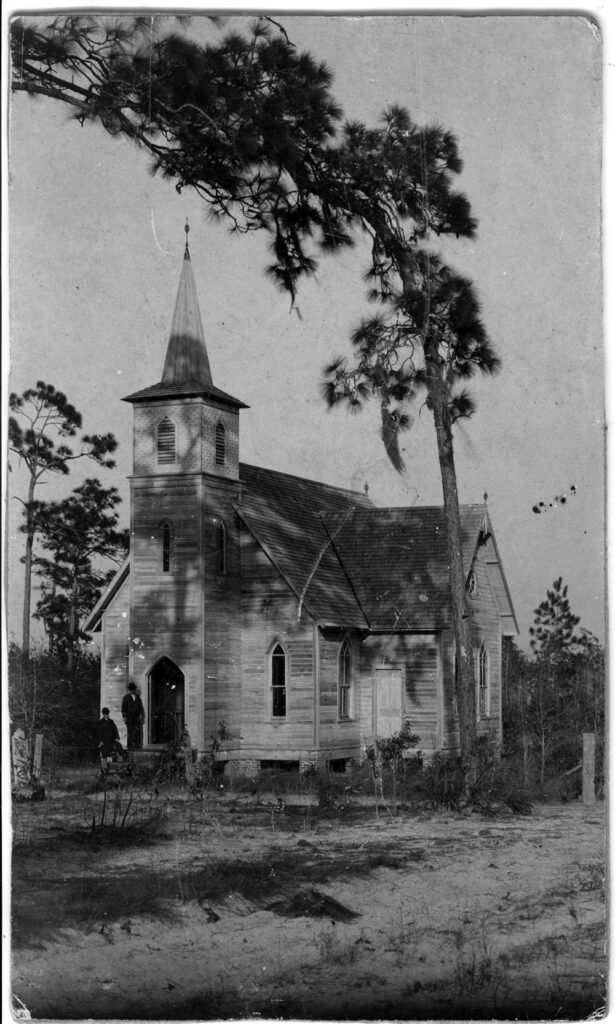

The Swedes established their first community church in 1878, which later became Lutheran. In 1891, the younger generation founded the Upsala Presbyterian Church, which still stands today at 101 Upsala Road.

New Upsala Lutheran Church. Photo courtesy of the Sanford Museum.

The Great Freeze of 1894-1895 devastated Central Florida’s citrus industry, leading to widespread abandonment of crops. The Swedes of New Upsala, heavily reliant on citrus, faced similar challenges. While many families left, 16 families remained, replanting their groves. Despite these efforts, New Upsala never fully recovered from the freeze’s impact.