By Pamela Schwartz from the Fall 2017 Edition of Reflections Magazine

“Surely a man who adds to the permanent, habitable, business and religious buildings of a city is a citizen worthwhile,” states an excerpt from C.E. Howard’s Early Settlers of Orange County, Florida, and such a man was Murry Schaeffer King.

Born in 1870 in Murrysville, Penn., and named for his hometown, Murry King was the son of Robert S. King, a wagonmaker, and Mary Jane Parks King. Murry King practiced carpentry and studied to become an architect while serving as a construction superintendent with the John Stuart Company.

In 1890, King married Ruth Ann Riley Dible, and the couple subsequently had seven children: Leroy (1890), Florence (1893), James B. (1894), Murry Jr. (1896), Merrit (1896), Edward (1901), and Pearl (1903).

A New Life in Orlando

Encouraged by a friend who had already made the move, King relocated his family to Orlando in 1904 and opened a cabinet shop at 18 E. Pine St. In 1912, from rooms 22 and 23 of the Watkins Block, King designed his first known structure: the Wescott Beardall House at 214 S. Lucerne Circle. Outside of his life as an architect, King was affiliated with the Knights of Pythias and the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks and was a member of the Orlando Chamber of Commerce, the Lions Club, and the Presbyterian Church.

King began designing homes for prominent residents, as well as many large commercial and public buildings that are still Central Florida landmarks today. He blended known architectural styles to create his own, which included elements from the Mediterranean Revival, Neoclassical Revival, and Prairie styles.

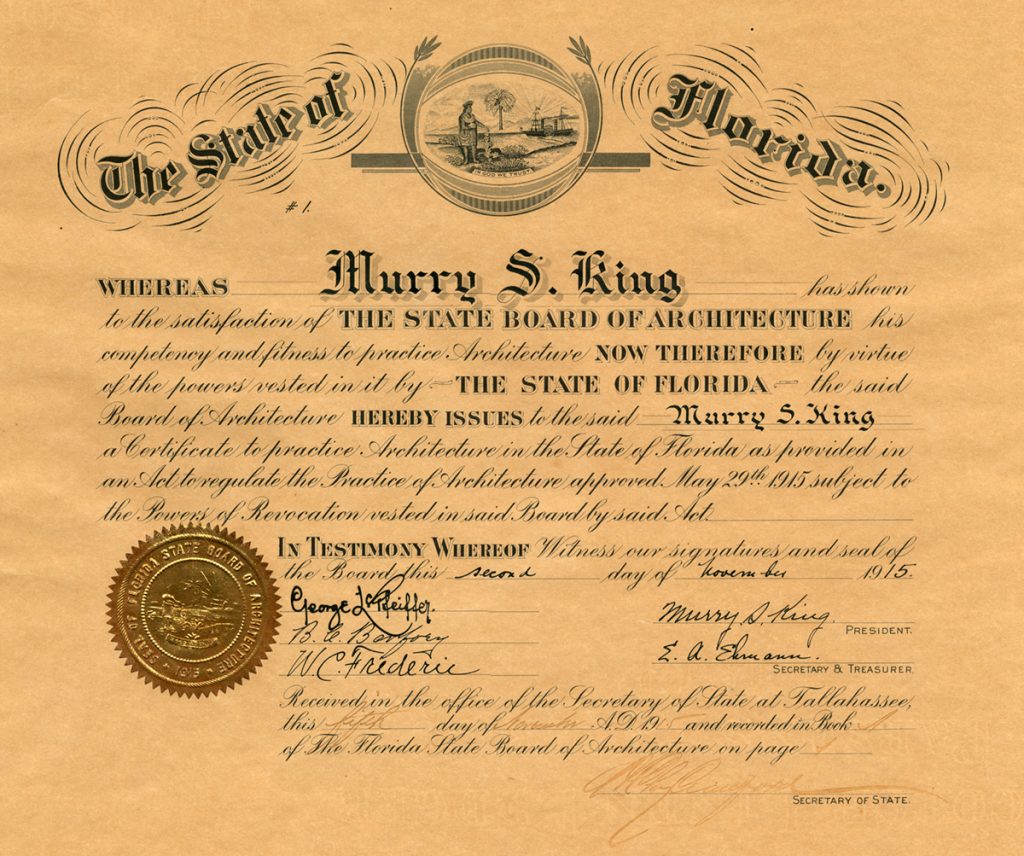

King’s accomplishments were myriad. He was a charter member and director of the Florida Association of Architects (FAA) and was appointed to the Florida State Board of Architecture, serving as its president for six years. A bastion for regulating architectural practice, King was the first registered architect in the state.

Toward a Florida Style

In 1924, the FAA appointed a committee including King and other notable architects – Ida Annah Ryan, Frank Bodine, George Krug, and Frederick Trimble – to attend a meeting of the Florida Lumber and Millwork Association. Here, the architects addressed a desire from workers to do away with the cookie-cutter reference plans they had been using to build homes, and to have the FAA design a collection that actually suited the climatic conditions of Florida.

In The Florida Circle, a publication devoted to the architectural, commercial, and community development of the state, in May 1924 the committee explained that they hoped to prevent

“financially irresponsible and even ignorant contractors, who bid low with the hope of getting a profit from the extra items which are not fully covered; though very essential to the completeness of the home, and the happiness of the owner.” Many of the committee’s plans were offered as a public service geared toward the small homebuilder to help reduce costs by standardizing as many architectural details as possible.

The period from 1910 through the mid-1920s was a booming time of growth and real estate development in Orlando. King flourished, alongside many of his well-known contemporaries. This collective of architects created a deliberate style that suited Central Florida. It was described in another article in The Florida Circle, which noted that “just as architects of old created styles to harmonize with their environment, so have the architects of Florida been creating, from native motifs, a style that is carefully adapted to the climatic conditions and surroundings of the state.”

This Florida style “has an individuality all its own and should have a fitting name to express its origins,” according to the article, which stated that the Florida Association of Architects would give a prize of $25 for the name of the style, to be selected. Contest submissions were to be sent to King by November 1924, with the winning name announced thereafter, but no record of a selected epithet has yet been found.

Though most of King’s nearly 30 credited designs are found in Orlando, both the Simpson Hotel and the First National Bank and Trust Building in Mount Dora have been attributed to him, with others in Ocoee and DeLand. He is perhaps best known to us at the History Center as the architect of our beautiful home, the 1927 Beaux-Arts style courthouse in the heart of downtown. Unfortunately, King died before this structure was completed, and his son James saw the project to fruition. King’s Women’s Club of Ocoee was also built after his death and was overseen by his son James.

Murry S. King died at age 55 at his Orlando home on North Orange Avenue on Sept. 20, 1925, of starvation, according to his death certificate. Though the circumstances are unknown, it appears he “had not been allowed anything to eat for 34 days by D. Height,” according to notes on the certificate. He is buried in Orlando’s Greenwood Cemetery.

Family Ties

I met with Melanie King, second great-granddaughter of Murry King, to talk about her family’s history and to receive a digital donation of some of the photos included in this article. Her father, Murray Stanton King, named for his great-grandfather but spelled differently, began doing genealogy in 1996. Through the Kings’ research, this long-time Central Florida family became involved with the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution, as well as the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Melanie hopes to educate her family about their rich history and share what she knows about Murry S. King with her three nephews to continue the legacy. Are you from a longtime Central Florida family? Please consider sharing your history with us.

Designs by Murry Schaeffer King

Athens Theater, 124 N. Florida Ave., DeLand (1921-1922) This Italian Renaissance structure opened as a silent-film and vaudeville theater and operated continuously for nearly 70 years. It was developed by L.M. Patterson, a native of Washington, D.C., who organized the DeLand Moving Picture Company. The opening night performance on Jan. 6, 1922, included a seven-reel silent film, The Black Panther’s Cub, plus a four-act comic play and four vaudeville acts.

Yowell-Duckworth (later Ivey’s) Department Store Building, 1 S. Orange Ave., Orlando (1913) This four-story structure was commissioned by Newton Pendleton Yowell and Eugene Duckworth for $61,000. It boasted the city’s first elevator and, in its early years, a rooftop garden restaurant and movie theater. A fifth story was an addition.

Seth B. Woodruff Residence, 236 S. Lucerne Circle, Orlando (1916) Woodruff was in the business of cattle, trucking, and orange growing and was also part of the small group responsible for the brick roads of Orlando built in 1895. This Prairie Style house was sold to attorney Lyman Beckes in 1934 and has since been remodeled and used as law offices.