by Whitney Barrett, Archivist

From the Spring 2019 edition of Reflections Magazine

Known during her lifetime as the “First Lady of Negro America,” Mary McLeod Bethune is remembered for her contributions as an educator and civil rights activist. Although the founding of Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona Beach, Florida, is probably her most well-known accomplishment, it is one of many.

In addition to being one of the first women to have established a historically Black college, Bethune was also very politically and socially involved at both national and international levels. She did not tolerate discrimination and continually fought for the rights of herself and others, whether the issue was voting rights, civil rights, or human rights. Although not a native, she called Daytona Beach her home for most of her life.

Early Years and Education

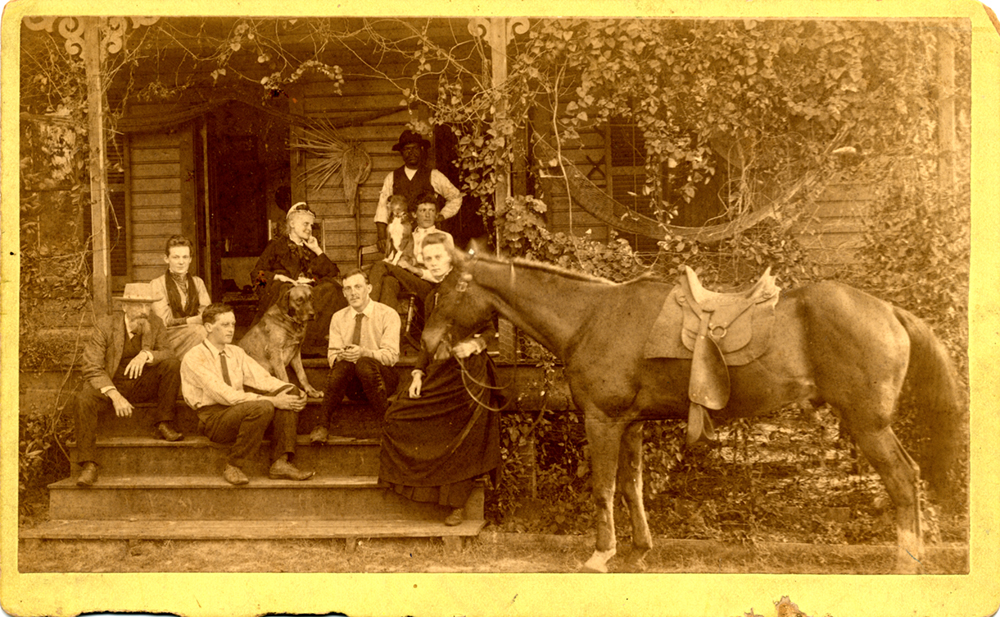

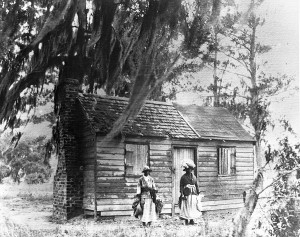

Mary Jane McLeod was born on July 10, 1875, in Mayesville, S.C. She was the 15th of 17 children born to her formerly enslaved parents, Samuel and Patsy McLeod, and was the first in her family born into freedom as well as the first to receive a formal education. However, before being given the opportunity to attend school, she helped support her family by picking cotton to sell, as many Black families did after slavery was abolished.

When Mary was around ten years old, she began her schooling at the Trinity Presbyterian Mission School in Mayesville. She proved to be a bright student who loved to learn. She once said, “The whole world opened up to me when I learned to read.” After graduating from the mission school, she was fortunate to receive funding from a woman named Mary Crissman to attend the Barber Scotia Seminary School in Concord, N.C., from which she graduated in 1894. She went on to Moody Bible College in Chicago with the hope of traveling to Africa to become a missionary, but her hopes were crushed when the missionary board informed her, after her graduation in 1895, that they were not sending Black people to posts in Africa.

Needing a new plan, she focused her attention on becoming an educator and returned back to Mayesville. She taught at the mission school where she first had learned to read and later moved to Augusta, Ga., to teach at Haines Normal and Industrial Institute. It was here under the leadership of Lucy Craft Laney that she became inspired to one day start her own school. She then went on to teach at the Kendall Institute in Sumter, S.C. It was there that she met her husband and fellow teacher, Albertus Bethune. They were married in 1898, and their only child, Albert McLeod Bethune, was born on February 3, 1899.

Starting a School in Florida

The Bethune family moved to Florida in 1899 and first settled in Palatka. Here Mary McLeod Bethune helped to start a mission school run by the Presbyterian Church. After about five years, she moved to Daytona Beach with plans to start her own school. When she and five-year-old Albert arrived in Daytona Beach in September 1904, all she had was $1.50 to her name (Albertus planned to join them later; however, the couple soon separated.)

Bethune’s lack of funds and support did not stop her from renting a house in which she opened the Daytona Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls on October 3, 1904. Her first class had five students.

Her mission was to educate young Black children, specifically girls. However, she did not underestimate the ways in which White philanthropists could contribute to her school’s success. It was common to see her in the beginning days of her endeavor riding her bike down the street, going door-to-door searching for support for her school. Early members of her board of trustees included Thomas White of the White Machine Sewing Company and John D. Rockefeller of Standard Oil.

White first came to visit Bethune’s school after he heard about her educational endeavors. He arrived at an unfinished four-story building with dirt floors and followed her around as she passionately explained her vision. He listened quietly, but what really caught his attention was an old Singer Sewing Machine the students had been using. A few days after his visit, a brand new White Sewing Machine arrived at the school. He continued as a generous benefactor.

Bethune first spoke to Rockefeller over the telephone to arrange a meeting. When she arrived on the doorstep of his winter home in Ormond Beach for the appointment they had arranged, he was quite surprised – he had been certain the woman he talked with on the phone was White! This did not deter Bethune, and she was able to persuade the oil baron to invest in her dream.

After expansion, several name changes, and a merger with the Cookman Institute (a co-ed school in Jacksonville), Bethune retired as president of Bethune-Cookman in 1942. She was named president emeritus and continued to be active in the school’s affairs, even briefly serving as president again from 1946-1947. With her home located on the campus, it was difficult for her not to stay involved!

Presidential Adviser

Though Bethune’s contributions to education are myriad, she was also extremely influential politically. She advised four United States Presidents: Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Franklin Roosevelt, and Harry Truman. Under Hoover, she worked on the National Committee on Child Welfare, and under Coolidge, she served as a delegate to the Child Welfare Conference.

During Truman’s presidency, she served as a consultant on interracial relations at the United Nations Conference on International Organizations in San Francisco in 1945, which established the U.N., and as a member of the United States delegation that traveled to Liberia in 1952 to attend the inauguration of President William Tubman. It was during this trip that the Liberian government awarded her the Star of Africa.

It was, however, under President Roosevelt that Bethune played a much larger role. He first appointed her as a representative on the advisory committee for the National Youth Administration (NYA). This led to her appointment as the first Black woman to head a federal agency – the Office of Minority Affairs. She was also the only woman on President Roosevelt’s Federal Council on Negro Affairs, more commonly known as the “Black Cabinet.” This was an unofficial cabinet of African Americans who advised Roosevelt on matters concerning the Black community.

Bethune was also good friends with first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and her mother, Anna. Eleanor Roosevelt even stayed at Bethune’s house twice, at a time when many white Southerners considered it quite scandalous for the first lady to stay in the home of a Black woman.

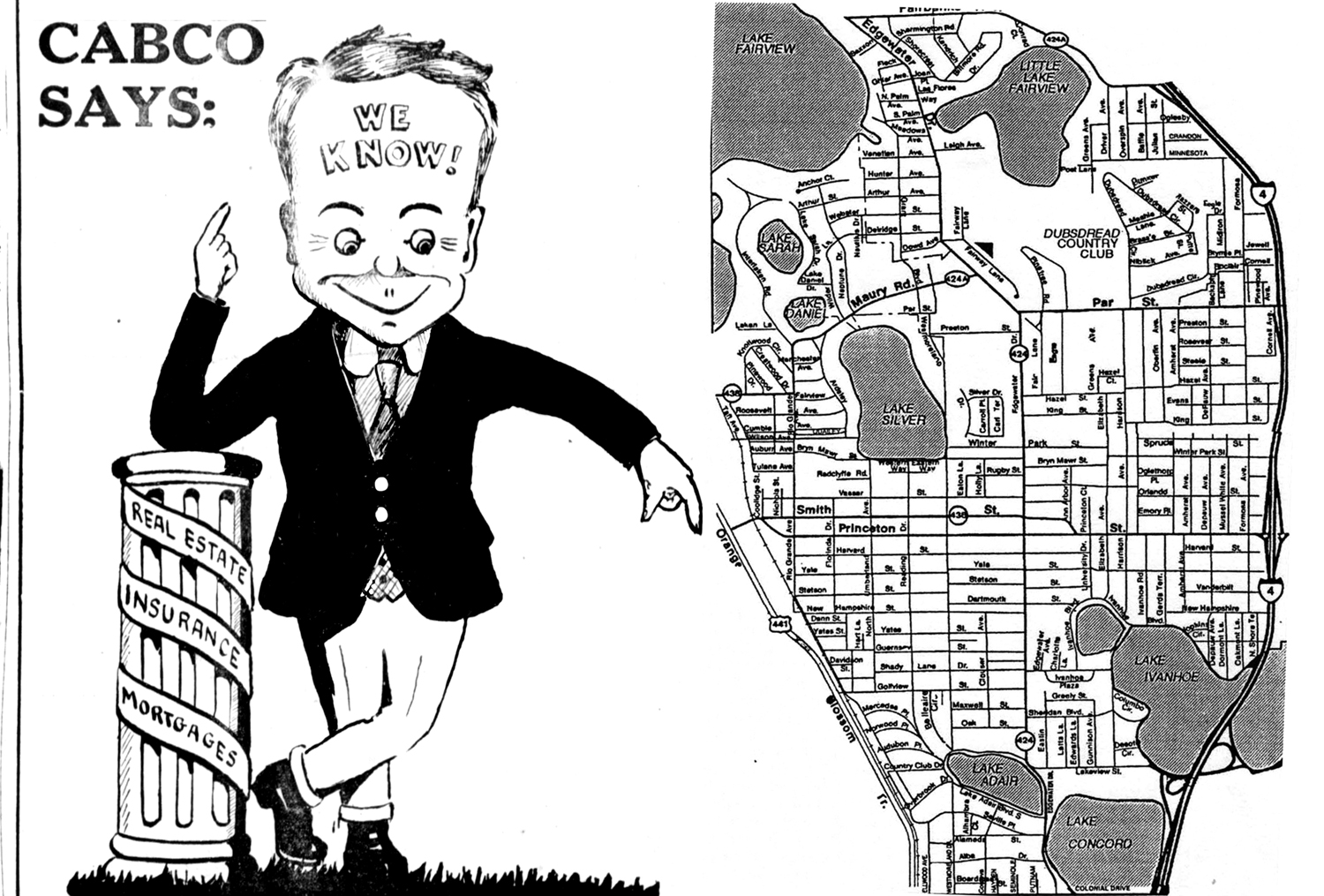

The Founding of Bethune Beach

Jim Crow laws affected almost every aspect of life in the South in the 1940s, even the beaches. This meant Black residents of Daytona Beach did not have an area of the beach easily accessible to them. Bethune’s solution was to create her own beach in the neighboring town of New Smyrna Beach. She reportedly said that the ocean was “God’s water” for everyone to enjoy. On Dec. 9, 1945, the board of directors for what would become Bethune-Volusia Beach (now known as Bethune Beach) met and signed a charter. The board was composed of Black individuals with local influence and status. Bethune was named treasurer. She envisioned a year-round resort where her people could enjoy themselves.

And as a businesswoman herself, Bethune always advocated for African American ownership of businesses and properties. As lots went up for sale and news spread, people all over the country began to capitalize on this investment opportunity. In May 2017, Volusia County placed interpretive panels and a historical marker on the site honoring the significance of the beach and its namesake.

The Bethune Foundation

As Bethune aged, she began to consider her legacy. On March 17, 1953, the Mary McLeod Bethune Foundation opened with offices in her home in Daytona Beach. Guests were allowed to come and tour to see where and how she lived. She wanted to inspire others and create a space where her story would live on. She also envisioned her home as a research facility and created plans for the arrangement and housing of her personal papers, which are now preserved in the Bethune-Cookman University Archives. In 1974, the home was recognized by the National Park Service as a Historic Landmark.

Death and Legacy

Mary McLeod Bethune passed away at the age of 79 on May 18, 1955, at her home in Daytona Beach. Her death was mourned by many and announced in newspapers across the nation. As requested in her will, she was laid to rest behind her house on the campus of Bethune-Cookman University. Both her home and her grave are visited daily by people who wish to pay tribute to her and to learn more about her life and contributions.

In February 2018, Florida’s governor, Rick Scott, signed a bill that provides for a statue of Mary McLeod Bethune to be placed in the National Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C. Her image will replace that of Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith, installed in 1922. She will be the first African American represented in the hall.

From the cotton fields of South Carolina, Mary McLeod Bethune rose to become one of the most prominent figures in African American history. She devoted herself to fighting for the rights of the less fortunate and disadvantaged. Her legacy and the strides that she made for equality should not be forgotten. To learn more about her, we recommend reading Mary McLeod Bethune in Florida: Bringing Social Justice to the Sunshine State by historian Ashley N. Robertson, Ph.D., of the University of Florida.

Images from the State Archives of Florida and the Library of Congress.