By Pam Schwartz, from the Fall 2023 Edition of Reflections Magazine

Note: This article contains profanity in quoted material.

On March 28, 1977, Orlando’s Tinker Field readied for the upcoming Spring Training game between the Texas Rangers and the Minnesota Twins. What might have played out like any other nine-inning affair instead turned into a national event when the Rangers’ recently benched second baseman, Lenny Randle, hauled off and punched his manager, Frank Lucchesi, during batting practice. This would set the stage for one of the more wild spectacles in Major League history, involving a now-legendary Central Florida criminal defense attorney.

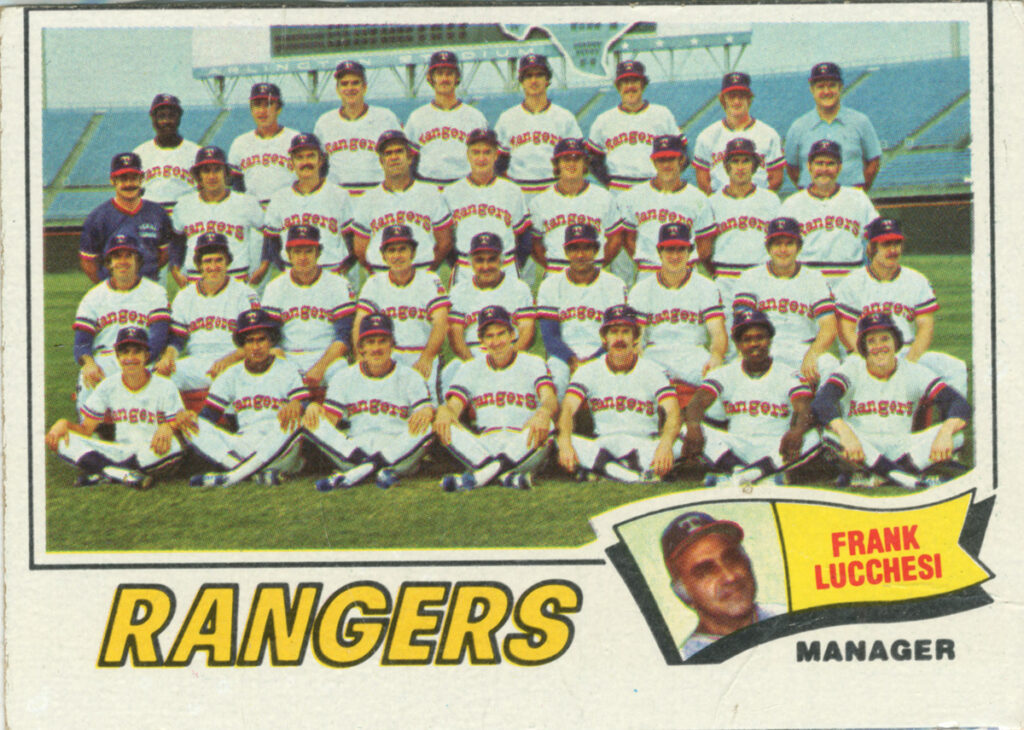

A 1977 baseball card for the Texas Rangers shows Lenny Randle in the front row, second from right, and Frank Lucchesi, second row center, as manager.

A First-Round Pick

Randle had been a first-round pick of the Washington Senators and tenth pick overall in June 1970. After little more than a season in the minors, he debuted as second baseman with the team in 1971. A versatile player, Randle split most of his time between second and third bases, also logging some playing time in the outfield. His best season statistically came in 1974, when he hit .302 with 157 hits in 151 games played, finishing 21st in balloting for the American League’s Most Valuable Player award.

By Spring Training 1977, however, the Rangers were ready to elevate 1975 first-round draft choice Bump Wills – son of 1962 National League MVP Maury Wills – to Randle’s starting role at second base. Randle didn’t think he was getting a fair shake at earning back his spot and had no qualms sharing his feelings on the subject. Just a week before the game at Tinker Field, Lucchesi in a session with the media explained, “I’m tired of these punks saying play me or trade me. Anyone who makes $80,000 a year and gripes and moans all Spring is not going to get a tear out of me.”

Though Randle was not mentioned by name, the remark seemed a clear reference to his discontent. The term “punk” – considered a major insult to a young Black man at the time – ignited a fuse inside Randle, as he would later confess during the civil suit against him.

During batting practice prior to the game, Lucchesi headed toward the dugout tunnel when Randle approached to confront his manager about his comments. As the two talked, and with no notice, Randle’s right hand shot out to strike Lucchesi. The 28-year-old Randle landed several swift blows before his 50-year-old manager hit the ground. Lucchesi spent a week at Orlando’s Mercy Hospital and needed plastic surgery to repair his cheekbone, which was broken in three places.

Randle was charged with assault but ultimately pleaded no contest to battery. His attorney, Richard Neuheisel, admitted that “Lenny knows he erred and there must be punishment. If we don’t think that punishment is fair, we intend to fight.”

During this first trial in early April 1977, Orlando Judge Maurice Paul – who notably was also involved in creating the Reedy Creek Improvement District – administered a tongue-lashing to Randle. “You should change your profession to boxing and get in the ring and give your opponent an equal opportunity,” the judge said, adding that “not only organized baseball but organized sports has suffered as a result of your action.”

Randle ultimately received a $10,000 fine and a 30-day suspension from Major League Baseball.

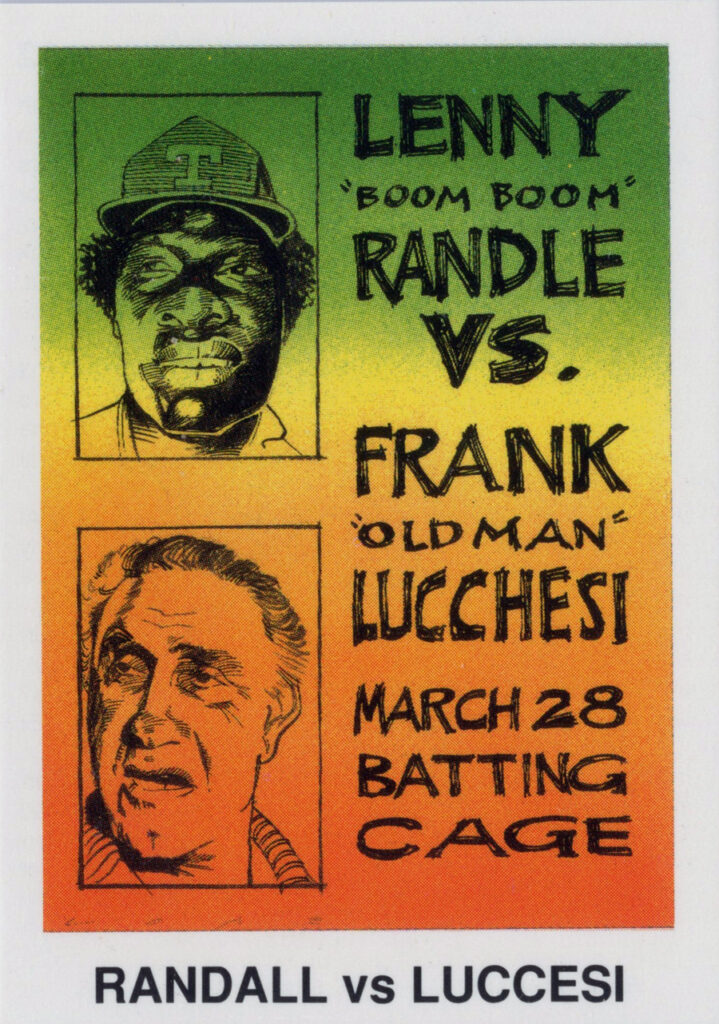

The Foul Ball Trading Cards company remembered the scene at Tinker Field on March 28, 1977, in a 1991 card.

A Second Case over Second Base

Before he could even serve his full suspension, Randle was traded to the New York Mets for cash and a player to be named later (Rick Auerbach). The Rangers ultimately parted ways with Lucchesi as well, firing him on June 21, 1977, but this duo’s brawl continued. A month after the first trial, Randle faced a civil suit filed by Lucchesi, who sought $200,000 in damages. Lucchesi also hoped to make an example of Randle. As he explained in an interview with the Miami Herald, “I’m going to make sure that nothing like this happens again. I’m going to make sure that no player ever hits another baseball manager, basketball coach, a football coach.”

A few days before the civil case was to be tried in late 1978, Randle and his new attorney, Thom Rumberger, had a disagreement on strategy that resulted in Randle firing his legal representation. “He is fearful of a Southern judge and Southern jury. The last few months we have had philosophical differences concerning the conduct of his claim. He believes it is a civil rights matter and I’m of the opinion that [it] is provoked alleged assault and battery,” explained Rumberger.

A deputy sheriff in the Orange County Courthouse recommended to Randle’s wife, Mercedes, that she go across the street from the courthouse (now home to the Orange County Regional History Center) to 127 N. Magnolia Ave. and request the help of attorney J. Cheney Mason.

Admitted to the Florida Bar in 1971, Mason was then in the first decade of a 51-year career that would make him one of the most storied criminal defense attorneys in Central Florida. In 2011, he would gain national attention as a member of Casey Anthony’s defense team. When Mercedes Randle came to his office in 1978, he was already recognized for displaying a willful disregard for convention, including not wearing a suit every day to work. That presented a problem if Mason were to act fast to aid Randle – attorneys had to appear in court in a suit – and Judge Bernard Muszynski had denied a court delay request from Randle, who was hoping to find new counsel. [Mason also became known for colorful speech, and quotes from him that follow are rendered without redaction in the interest of historical accuracy.]

In a 2022 oral history interview with the History Center, Mason looked back at the Randle case. It began for him as he gathered as much information as possible from Mercedes Randle during a car ride to and from his home in Altamonte Springs so he could change into the required suit.

When Mason arrived back at the courthouse, he walked into the courtroom during the middle of a doctor’s testimony showing x-rays of a fractured bone in Lucchesi’s face. The scene of the young defendant Randle being left without representation infuriated him. “Here’s two lawyers, a jury in the goddamn box, and here’s this 22-year-old Black kid [Randle was 28] sitting at this big table without even a fucking yellow pad,” Mason said. Throughout his career, he deeply believed everyone was entitled to a defense.

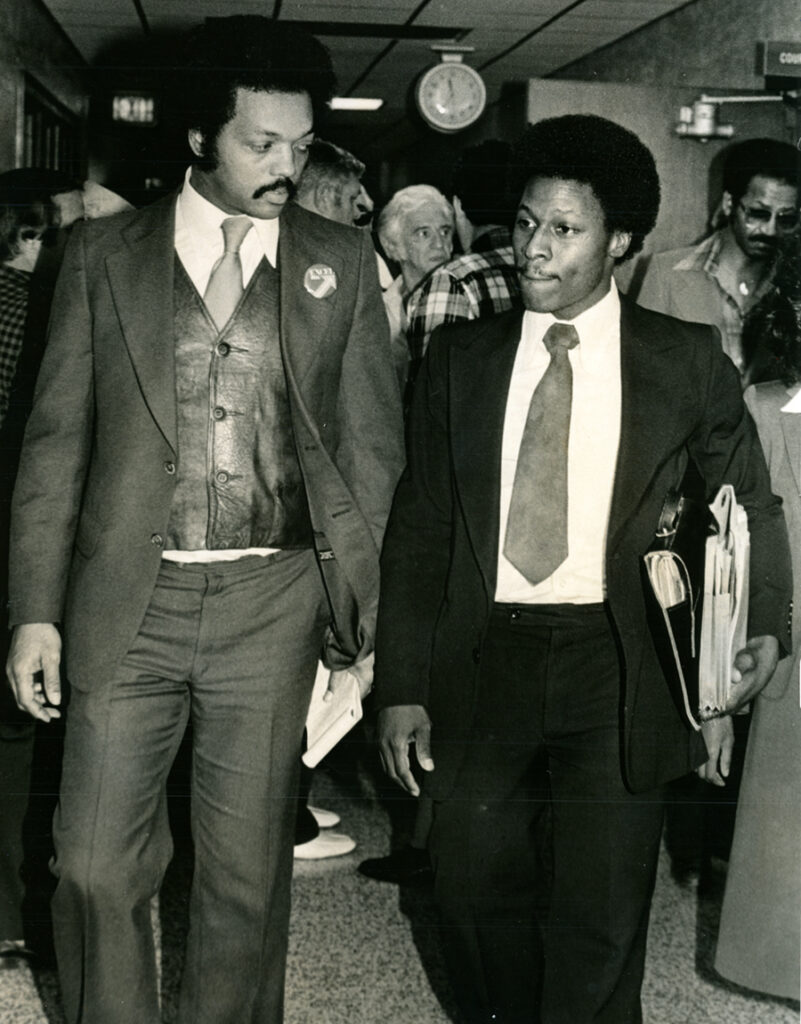

The Orlando Sentinel’s Red Huber snapped the Rev. Jesse Jackson (left) with Lenny Randle at the Orange County Courthouse on Dec. 7, 1978.

Trial Attracts Big Names to Orlando

The defense strategy of Mason and his partner Donald Lykkebak claimed Lucchesi was aggressive and racist, citing figures that showed the Rangers had gone from 13 Black players to just four while he was manager, Orlando Sentinel sports editor Larry Guest noted in a December 1978 column.

“People who know baseball and Frank Lucchesi know such suggestions are pure poppycock,” asserted Guest, who closely followed the trials.

The case drew notable individuals to town in support of Randle, including civil rights activist Jesse Jackson, Randle’s former manager Billy Martin, future Hall of Famer Lou Brock, and the then recently retired home-run king Hank Aaron.

Mason recalls Jackson visiting him at his office. The case had received national publicity, Jackson said, and he wanted to make sure Randle received a fair trial. Mason explained that he would do his best for Randle but bluntly told Jackson not to interfere. “I’m not a racist,” Mason remembers telling Jackson. “We’re doing a great job and we’re going to win this goddamn case. But if you get out there on Orange Avenue in downtown Orlando and start parading and stuff, I’m gonna lose.” Consequently, Jackson and his entourage supported Randle by appearing in the courtroom but did not demonstrate publicly.

A few days into the trial, Mason received a phone call from the commissioner of baseball, Bowie Kuhn. He and two of his associates requested to meet Mason downtown at the Harley Hotel (now the Metropolitan) across from Lake Eola at 151 East Washington. Mason felt leery of the arrangement, he recalled in 2022, and described the scene inside the hotel room at the Harley.

“One of these giants, alongside him is another giant, they’re there protecting Commissioner Bowie Kuhn against me. I looked at them and they were not friendly, they were not welcoming, they were not anything. I just looked at one guy and I said, you know, I don’t know what your job is, but it is clear to every one of you all that you can beat me up, easily. But here’s one thing, I will fucking leave bite marks on you.”

Kuhn didn’t like the negative publicity the case had drawn and tried coercing Mason into telling Randle just to pay the fine so it all could be settled. Mason told Kuhn to pay it himself as he took his leave.

In December 1978, Lucchesi’s civil case against Randle settled for $20,000, significantly less than Luchessi had been seeking. Billy Martin pitched in $10,000, and Randle’s mother-in-law offered to pay the other half.

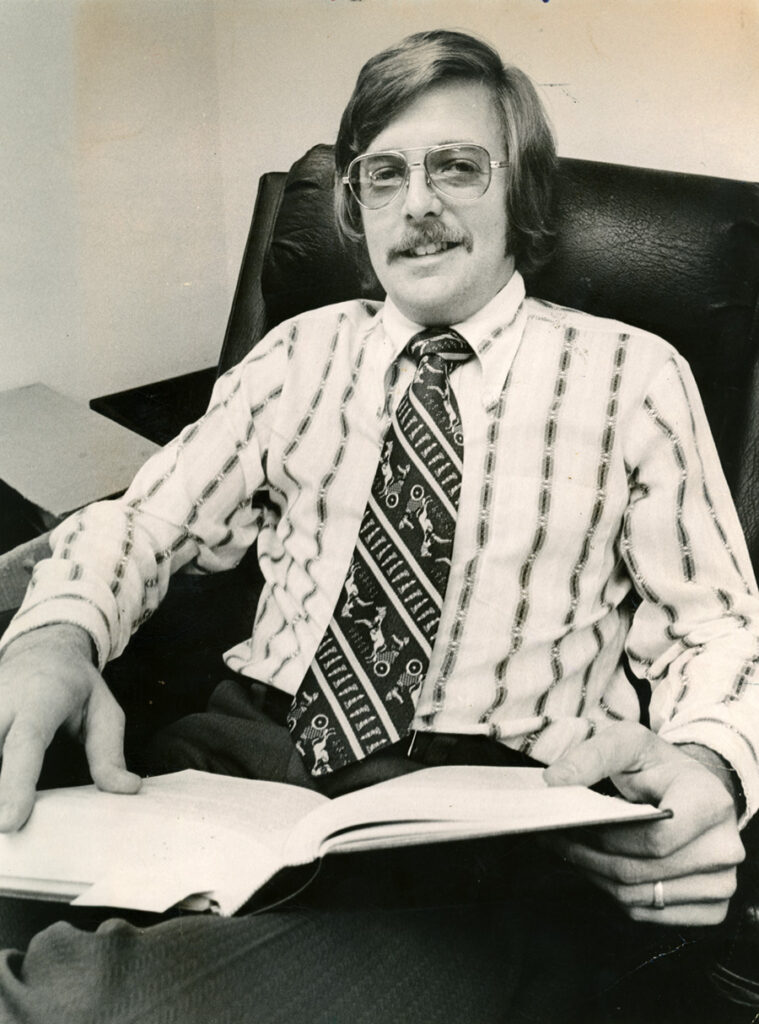

J. Cheney Mason early in his 51-year career as a defense attorney.

The Most Interesting Man in Baseball

Following his time with the Rangers, Randle would go on to play on several Major League teams including the New York Mets, New York Yankees, Chicago Cubs, and Seattle Mariners. He was part of numerous memorable moments in baseball history, including playing in the “10 Cent Beer Night” riot at Cleveland Stadium in 1974, standing at the plate in Shea Stadium during the New York City blackout of July 1977, and blowing a baseball across the foul line during a game at the Kingdome while playing for the Mariners in 1981 – perhaps his most humorous performance.

In 1983, Randle became the first American Major Leaguer to play baseball in Italy, where he set the record for the longest home run in the Italian Serie-A1 league. Following his time in Italy, he returned to Florida in 1989 and played in the Senior Professional Baseball Association for the St. Petersburg Pelicans. He speaks several languages, wrote, published, and performed a hip-hop song, and dabbled in stand-up comedy. Rolling Stone magazine once called him “The Most Interesting Man in Baseball.”

Lucchesi went on to hold various minor and major league roles managing and scouting over the next decade, most notably with the Chicago Cubs, before retiring from baseball in 1989. Each of the lawyers and judges involved, Mason included, would continue on to notable accomplishments from changing long-standing case law to protecting the Everglades. This one seemingly inconsequential event in Orlando’s history included many already, or soon to be, powerful players and prominent places in Central Florida’s landscape.

In the end, a March 29, 1977, story about Randle and Lucchesi’s Tinker Field incident by Dallas Times Herald reporter Blackie Sherrod offers an ironic coda to their saga. “In a corner of the dugout, by the bullpen telephone, while Rangers players milled about in stunned aimlessness [due to Randle’s outburst], a small white card glared from the wall. It was the lineup for Monday’s game. The second line read: Randle, 2b.” Randle, it seems, would have received his fair shake after all.

Become a member of the History Center to enjoy articles like this in the print version of Reflections magazine – mailed directly to your home or office twice a year!