By Travis Puterbaugh from the Fall 2024 edition of Reflections Magazine

On the morning of Oct. 26, 1964, readers of the Orlando Sentinel woke up to a historic headline: “Welcome to Central Florida, Mr. President.” The occasion of President Lyndon Johnson’s visit to Orlando marked the first time that a U.S. president had spent a night in this city while in office and the first visit by a sitting president since Harry Truman in 1949.

Johnson – who became the nation’s 36th president on Nov. 22, 1963, following the assassination of John F. Kennedy – had previously campaigned in Orlando on Oct. 12, 1960, as a vice-presidential candidate. Then, Johnson had hoped that an appearance in Central Florida would swing the state into the Democratic column. The Kennedy-Johnson ticket had fallen short in 1960 by 3.02 percent, and in Orange County a whopping 70.98 percent of the vote went to Richard Nixon. Could 1964 finally be the year Florida turned blue for the first time since 1948?

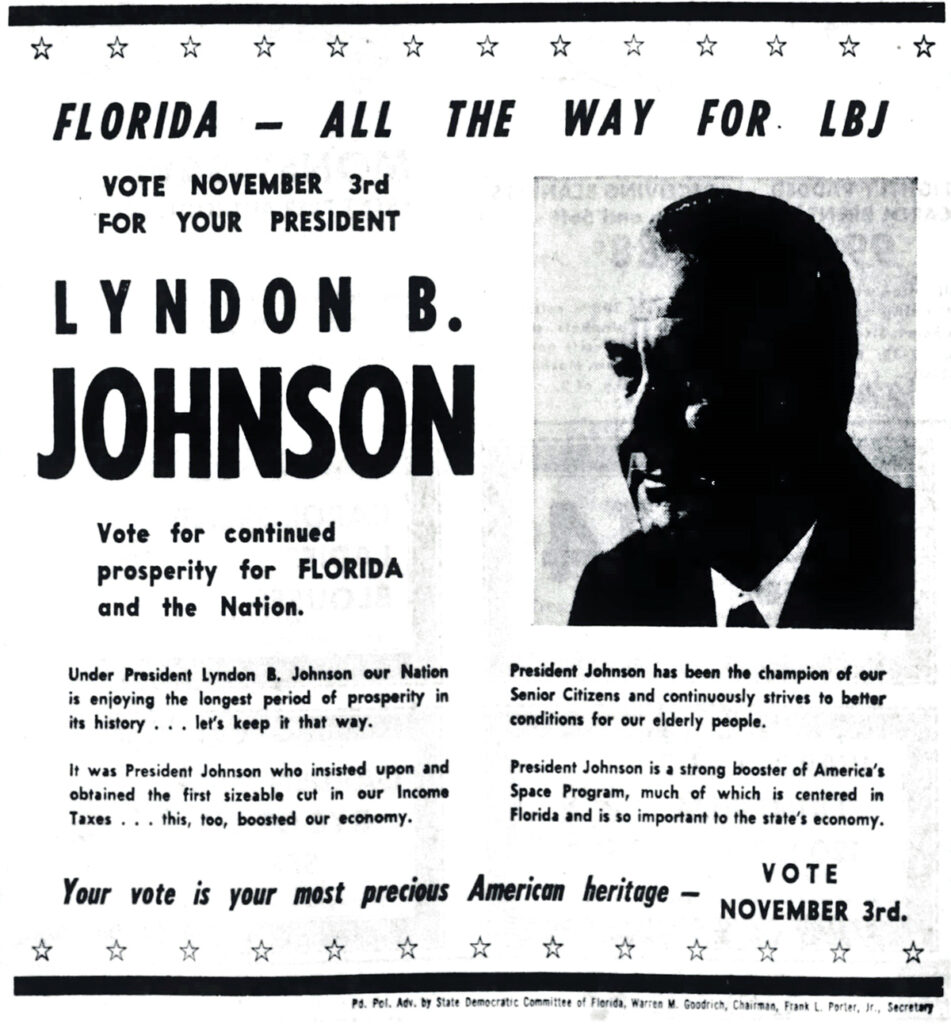

The State Democratic Committee of Florida urged votes for Johnson in an Orlando Sentinel ad on Oct. 26, 1964, during the president’s visit.

A powerful ally

The president certainly had an ardent supporter in Orlando Sentinel publisher Martin Andersen, one of the most influential voices in Central Florida and a close friend of Johnson’s from Andersen’s days in Texas. In a July 3, 1955, front-page editorial, the Sentinel boldly endorsed the 46-year-old Johnson for the Democratic nomination for president despite the “moderately severe” heart attack he had suffered just a day prior. Though Adlai Stevenson II of Illinois would eventually earn the 1956 nomination, the Sentinel again endorsed Johnson in 1960 during his primary fight against John F. Kennedy.

Johnson had long enjoyed popularity among Democrats in Florida. Now that he was in the White House, his friend Andersen had a direct line to the most powerful man in the world. Andersen’s influence with the president played no small part, for example, in the establishment of the Naval Training Center in 1968, following the closure of the Orlando Air Force Base in late 1967.

Their friendship certainly extended to the Sentinel’s coverage of the 1964 presidential campaign, in which the paper came out strongly in favor of Johnson and proved critical of Republican nominee Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona, a vocal opponent of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. All this took place at a time when Johnson’s selection of the liberal senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota and the passage of the Civil Rights Act made Johnson unpopular among many southern voters of both parties.

President Johnson, alongside friend and Orlando Sentinel publisher Martin Andersen (right front), works the reception line upon his arrival in Orlando on the night of Oct. 25, 1964.

“Hello, Lyndon!”

Johnson recognized the importance of Orlando in Florida’s growth and chose the city as the site of a major campaign stop, and Central Florida residents rewarded Johnson with their warm reception.

The president arrived from Miami via Air Force One at the McCoy Civilian Jet Terminal just after 9:30 p.m. on a rainy Sunday, October 25. An estimated crowd of nearly 8,000 gave Johnson an enthusiastic welcome, while the Winter Park High School band serenaded him with “Hail to the Chief” and a rendition of his “Hello, Dolly!” inspired campaign theme song, “Hello, Lyndon!” Tellingly, Johnson was accompanied in his limousine by Florida Gov. Farris Bryant and by Andersen, who sat between the two leaders.

Upon the motorcade’s arrival at the Cherry Plaza Hotel on Lake Eola, the president shook hands with well-wishers for 23 minutes and even climbed onto the hood of a police cruiser to tell the assembled how much he loved being in Orlando.

The next morning, Johnson embarked on a motorcade to the Colonial Plaza Shopping Center, where he would deliver a campaign speech. Given President Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas just 11 months prior, providing a secure motorcade for the president was top priority for Orlando officials. Windows on the upper floors of buildings along the route were to remain closed, and people were forbidden from assembling on rooftops for a better view. Additionally, the route was monitored by helicopters, leaving nothing to chance.

Along this motorcade route, the crowd was overwhelmingly positive, with only a smattering of pro-Goldwater signage, and Jean Yothers of the Sentinel took special note of the youngest among the crowds, writing that “Central Florida children greeted the tall Texan as if he were Santa Claus.”

The newspaper called Johnson’s visit the most “overwhelming turnout for any event in the history of Orlando,” with approximately 110,000 Central Floridians coming out to see the president, including 50,000 in the shopping center parking lot alone for his speech.

From a platform just south of Belk’s department store, Johnson opened his remarks at 9:45 a.m. by saying, “I like Orlando! After that warm and friendly welcome last night, and your wonderful hospitality this morning, I am quite ready to accept Orlando citizenship.”

Johnson delivered his campaign stump speech, touching on social security, the space race, the economy, and taxes, as well as two references to Martin Andersen. In closing, Johnson took a jab at the Goldwater campaign’s “In Your Heart You Know He’s Right” slogan by saying, “you want to select the person that, in your conscience, you know has the experience, the judgement, and that you know will do what is best for his country.”

President Johnson’s motorcade travels north on Orlando’s Orange Avenue, passing the headquarters of the Orlando Sentinel.

Election Day effects

In the end, did Johnson’s visit to Central Florida pay off on Election Day? Orange County – which The Corner Cupboard newspaper described as “one of the most Republican areas in the country” at the time – went solidly for Goldwater on Nov. 3, 1964, with the Republican nominee earning 56.10 percent of the vote. Republican candidates for president would go on to win in Orange County for the next eight elections. (Changing demographics in the county over the last two decades, however, have resulted in a voter shift, producing Democratic victories in every presidential election since 2000.)

Johnson did wind up carrying the state of Florida by 2.30 percent of the vote in 1964, in the process earning the state’s 14 electoral votes. In only one other state – Idaho – was the vote quite so close for Johnson, who won the election over Goldwater in a massive landslide, with 61.1 percent of the popular vote and 486 electoral votes.

William Brawley, the Democratic National Committee’s regional campaign director in the south, credited Andersen’s endorsement of Johnson as a major factor in Florida going Democratic for the first time since 1948.

“There is ample reason to believe,” he said, “that without the editorial endorsement of the Sentinel and the newspaper’s subsequent promotion of the president’s appearance in Orlando near the end of the campaign, the Democrats might have lost Florida for the fourth consecutive time in a presidential election.”