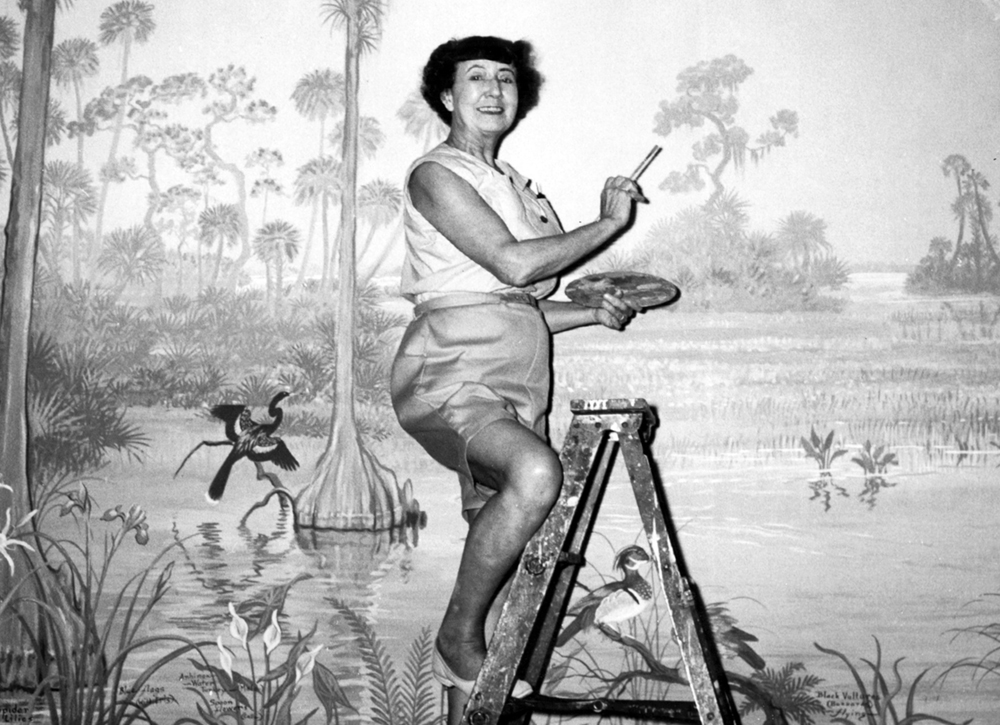

Courtesy of the Joy Postle Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Central Florida, Orlando

By Denise Hall, from the Spring 2009 edition of Reflections magazine

The scene was Ivey Lane Elementary School in the early 1980s, and the artist who would perform for the students was old enough to be their great-grandmother.

She wore thick glasses and a knitted hat, and she had long legs like the leggy water birds she loved. Some folks even called her the “Bird Woman.” She danced and sang while at the same time drawing birds on a series of easels – a routine she perfected through four decades in performances all over Florida.

But Ivey Lane on Orlando’s west side in the 1980s, where many kids struggled with poverty, was a far cry from, say, Winter Park society in the 1940s. Would the children roll their eyes? Make fun of her?

Not a chance. When she got going, Joy Postle had them mesmerized. They had never seen anyone like her, because there was no one else quite like Joy Postle: artist, champion of wildlife, poet, traveler, free spirit, inspiration.

“Her name was a true description of her,” says award-winning artist Jennifer Myers-Kirton of Mount Dora, who studied with Postle. “I owe Joy Postle so much. . . . She was an awesome artist against awesome odds. Women just did not do what she did, and very few men could have.”

So, what did Postle do in her remarkable 93 years? For one thing, she broke ground in using Florida’s environment as a subject for art. “She painted wildlife when it wasn’t trendy to paint Florida wildlife,” says Peggy Lantz, former editor of the Florida Audubon Society’s magazine, Florida Naturalist. And, to see her subjects, Postle ventured into the wild. “She waded through swamps, climbed trees, endured bugs and stayed up all night” to observe her beloved birds and other wildlife, according to her Orlando

Sentinel obituary in 1989.

In the process, by hook or by crook, she cobbled together a living as an artist, with her husband and manager Robert Blackstone, at a time when art was often considered something a woman might do only as a gentile hobby. During much of Postle’s lifetime, conventional wisdom said that a woman’s place was in the home.

But from an early age, Postle refused to be boxed in by convention. “Joy told me once that she had performed for Carl Sandburg,” her step-grandson Daren Kelly remembers. After her show, the famous poet approached her, took her hand in his huge one, and said, “I can see you’re a seeker. I’m a seeker too!”

Migration toward Florida

Postle’s journey through life began in 1896 in Chicago, where she studied art and music at the Art Institute of Chicago on a scholarship. By the 1920s, she had moved with her family to Idaho and was working as an artist and decorator when she met journalist Robert Blackstone, who eventually became her husband and manager.

After marriage in 1928, the couple hit the road pulling their “flivver bungalow” – a homemade travel trailer – and stopping to take on art commissions as they made their way through the West. Later, Postle would say they decided to head toward sunny Florida after her watercolors froze on a blustery day in Utah’s Zion National Park.

The couple arrived in the Sunshine State in 1934 and continued their nomadic lifestyle as they camped, hiked, and chronicled wildlife across the entire length and breadth of Florida. Eventually Postle and her husband settled on the shore of Lake Rose at Orla Vista, near Gotha, and built a simple house and studio. During the late 1930s, Postle was selected for the Works Progress Administration artists’ project that enhanced public buildings with murals during the Great Depression.

Then, from about 1937 until her death, Postle’s life was dedicated to her art – her sole livelihood – especially the murals in sites that ranged from Texas to the Carolinas. In Florida she painted murals for such varied locals as the First National Bank of Stuart, the Fort Gatlin Hotel in Orlando, and Casa Iberia at Rollins College in Winter Park. Painting into her 80s, she even created artwork for Discovery Island and the Fashion Square Mall in Orlando. She supplemented her income by doing commissioned paintings of beloved pets.

Courtesy of the Joy Postle Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Central Florida, Orlando

Performance Artist

Postle combined her artistic abilities, her musical talents, and her love for Florida birdlife in performances she called “Glamour Birds of the Americas.” She would describe the birds she loved and paint them in the presence of an audience, with her husband, Bob, accompanying her with recordings of music and bird calls he had recorded himself, Daren Kelly recalls.

“She would even mimic the fascinating mating dances the egrets and herons would perform for each other. Even in old age, Joy could still mime these dances. Bob promoted and arranged these demonstrations, by acting as her manager,” Kelly says.

The show brought “the beautiful feathered creatures of the mysterious swamps and waterways to her audience in songs, witty stories, original verse, and pictures,” the Winter Park Topics newspaper noted in 1945.

Courtesy of the Joy Postle Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Central Florida, Orlando

Legacy of Joy

Postle faced tragedy in her life. In 1968, a kerosene heater in the Lake Rose home ignited a fire that killed her beloved husband and injured her severely. But she impressed friends and colleagues with her resilient and buoyant spirit.

“She was exuberant, just delightful,” says editor and author Peggy Lantz, who met Postle late in her life. Daren Kelly, an accomplished stage and TV actor, remembers her “unbounded curiosity, her positive, forward-thinking spirit, and her ability to summon up a great deal of energy to go ‘on a trek’ even in late old age. She was an inspiration to me, as I too have chosen the very challenging vocation, as a theater performer.”

So, after the fire and a lengthy recovery, Postle summoned that energy to perform her “Glamour Birds” show again, in venues including the Ivey Lane school where she charmed the young students. And even in her last few years in a nursing home, she continued to paint. She passed away in 1989, after 93 adventurous, original years.

By re-interpreting nature with her own artistic flair, Postle turned a spotlight on the natural Florida that would be carelessly threatened during her lifetime by unchecked development. In the 21st century, renewed interest in environmental issues puts Joy Postle’s story right back where she would most like to be – in the catbird seat.