By Tana Mosier Porter from the Winter 2016 issue of Reflections from Central Florida, the magazine of the Historical Society of Central Florida

In his book “Division Street: America,” published in 1967, historian Studs Terkel dismissed the conjecture that Chicago’s Division Street represented an actual boundary between races or classes. “Although there is a Division Street in Chicago, the title of this book is metaphorical,” he wrote. Many American cities have a Division Street that at one time probably divided something, most likely early land ownership or city limits.

The popular belief that Orlando’s Division Street was intended to mark the division between Black and white residents contradicts historic patterns of settlement showing that the name predated any such division. Division Street probably marked the city’s western boundary when it appeared on city records as early as 1886, well before the city’s population had grown large enough to be divided.

Racial separation would have been impossible before Emancipation, when enslaved people often lived in close proximity to their white holders. The pattern of residential mixing in older cities and towns continued even as segregation developed during Reconstruction, but as separation became more pervasive, the Black population, historically scattered throughout Orlando, settled into three enclaves: Jonestown on the east side of the city and Callahan and Parramore/Holden on the west side.

The Myrtle Shop at the corner of Church Street and Division, circa 1955.

Black and white in Parramore

Orlando’s 1891 city directory lists Black individuals separately, showing their occupations and places of residence. Most lived either in Jonestown or west of the railroad in the neighborhood that later became the segregated community of Parramore. Originally planned with big houses along Central Avenue (now Central Boulevard) for the white employers and small houses behind them for the Black household help, Parramore remained for some time a mixed Black and white neighborhood.

In 1915 the city directory showed white families on Central Avenue west of the railroad tracks and Black families on Bryan Street from Robinson Street to Central Avenue. Residents on Garland and Hughey streets were white with a few Black neighbors, while mostly Black individuals lived on Division Street, but with pockets of white residences. Bryan, Hughey, and Garland streets all paralleled the railroad between Division Street on the west and the railroad tracks on the east.

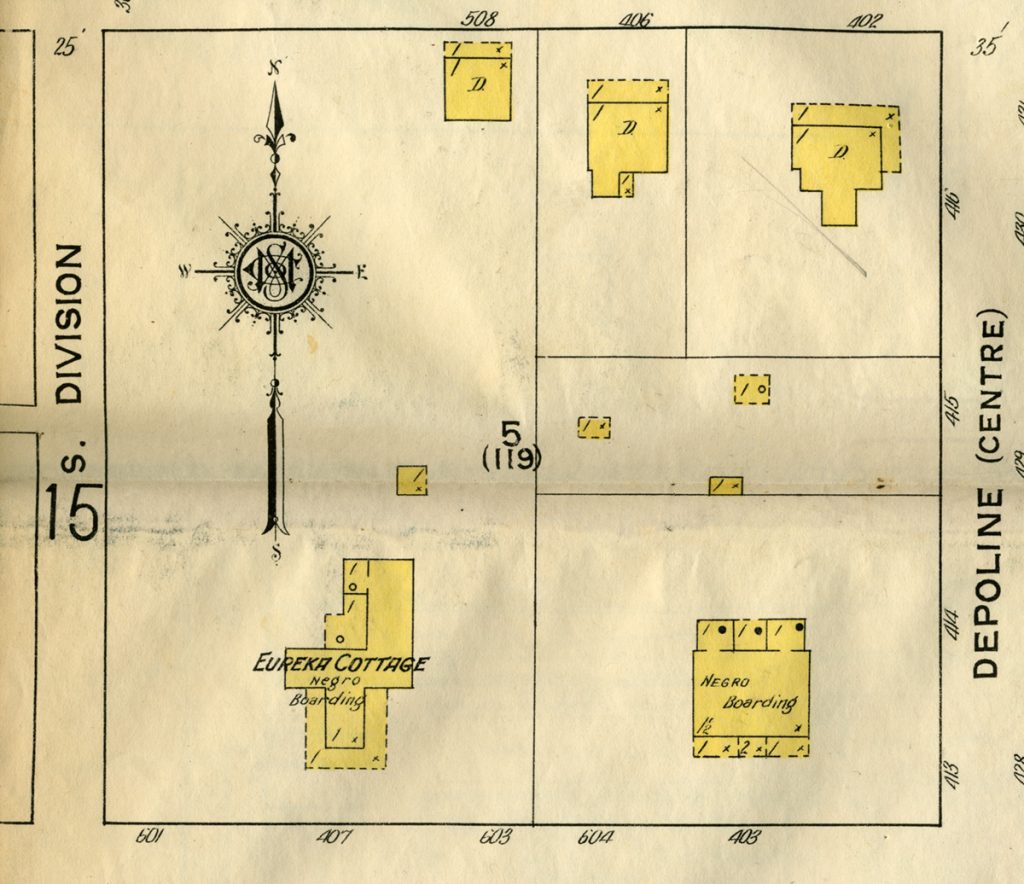

Detail from the 1913 Sanborn Map Co. fire insurance map of Orlando showing the designation “Negro Boarding” east of Division Street.

Systematic separation

Orlando began in the 1920s to systematically segregate the Black community. The city established a zoning commission in 1923 and unofficially designated separate areas for Black residences in 1924. One area lay west of Division Street near the area that later became the Griffin Park and Carver Court public housing projects. The other began at Hughey Street and extended west on Washington Street to Westmoreland and back along Robinson to the beginning point. In neither case was Division Street a designated boundary.

In 1927 Orlando adopted a zoning code identifying most of these areas, already occupied by Black residents, as industrial, but evidently still suitable living places for them. White citizens began to demand that Black residents be removed from their homes, especially those in Jonestown, where they had lived for a half-century, and be forced into the new segregated areas.

An undated photo shows owner Georgia Wallace (left) with other beauticians and patrons at Wallace’s Beauty Mill on Church Street in Orlando.

Griffin Park opens in 1940

The solution to getting rid of Jonestown came from the federal government in the form of the Griffin Park public housing project, opened in 1940. Built on property the city owned at Gore and Division streets and Avondale Avenue, just east of the city dump in the southern area designated for Black occupancy, the Griffin Park project possibly represented the first time Division Street was named as a boundary for Orlando’s segregated Black district west of the railroad. But when Orlando officials selected the Griffin Park site, they cited city ownership of the land rather than the site’s location west of Division Street.

In 1943 Orlando’s planning commission, preparing to issue a new zoning map in 1944, created a master map showing where Black residents lived at that time. The two areas reflected the sections designated for them in 1924. The southern area, bounded by the Orange Blossom Trail, Division, South, and Gore streets, included the Griffin Park project, by that time in operation for two years. North of Griffin Park, Hughey Street seemed to mark the eastern boundary in 1943.

The boundaries changed in 1962, when Interstate 4 cut through Parramore, taking out part of Division Street and a section of Griffin Park, as well as the eastern ends of most Parramore east-west streets. The raised expressway permanently closed some streets, isolating Parramore and creating a new boundary for the still-segregated community.