By Whitney Broadaway from the Fall 2017 edition of Reflections magazine

At the close of the Civil War, Moses and Daphne Crooms, freed slaves from the Goodwood Plantation in Tallahassee, moved east about 40 miles to Monticello. After a few years there, the Crooms family moved south and settled in Orlando. Moses Crooms was a skilled carpenter and became well known in the area. Daphne, who was said to have received some level of education on the plantation, became passionate about passing the love of learning on to the rest of her family. The Croomses had seven children: Walter, Moses Jr., A.C., Henry, Joseph, Virginia, and Mamie. Many of them became educators and ministers, including Joseph Crooms, who founded the Crooms Academy in Sanford.

Roots in Sanford

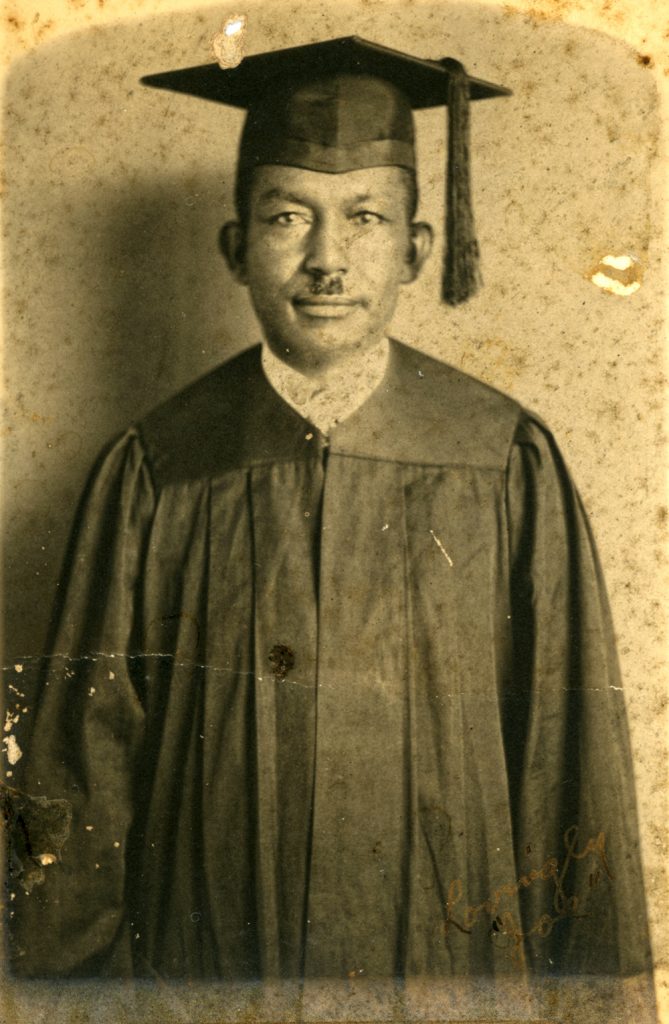

Joseph Nathaniel Crooms was born on June 17, 1880. He went to high school at Johnson Academy, later named Jones High School, in Orlando, and continued on to earn a degree from the Florida Normal College in Tallahassee, the precursor of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University. Crooms also studied at the Hampton Institute in Virginia and the Florida Institute in Live Oak. After teaching in Cocoa and Suwannee County, he settled in the Georgetown neighborhood of Sanford and began working at Sanford’s oldest school for black students, founded in 1885.

Joseph Crooms started at the Georgetown School as principal in 1906 and immediately began making changes. He had five teachers and 240 students under his care at a school that only went up to the eighth-grade level, was in session for a maximum of six months of the year, and was housed in an inadequate structure on Cypress Avenue and Seventh Street.

There is no question that “Colored School No. 11,” as it was listed in the Orange County Public School Ledgers, was not up to Joseph Crooms’ standards. (Sanford was a part of Orange County until Seminole County was formed in 1913.) With the help of the teachers and the community, Joseph built a new two-story wooden building his first year as principal at 1101 S. Pine Ave. and renamed the school Hopper Academy.

The building still stands today and has been used as a library, a church, an after-school center, and a community meeting place since 1968, when it ceased to operate as a school. Crooms also expanded the curriculum to extend to the 10th grade and extended the school year to last seven to eight months. After all this work, his meager starting salary of $50 per month, as compared with the $125 per month paid to the principal at the white high school, was increased to a still meager $65.

On July 6, 1911, Joseph Crooms married Wealthy Richardson, a fellow educator from Winter Park. Wealthy had received degrees from Claflin University in South Carolina as well as South Carolina State College. Before joining the staff of Hopper Academy in 1908, she taught at the Daytona Literary and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls, which would later become Bethune-Cookman University. A year after their marriage, the couple’s only child, Nathalie, was born.

Building the Crooms Academy

Even with all the improvements, Hopper Academy was still a long way from closing the racial divide in education that Joseph and Wealthy Crooms were fighting against. The school still only went up to the 10th grade and focused on trade skills, such as carpentry and agriculture – skills that, at the time, were considered to be the only things necessary for a black student to learn.

The Croomses knew they could do better than this stunted curriculum, and Sanford was fast outgrowing its only black school, so in 1926 they left Hopper Academy and founded a new institution. They acquired 7.5 acres on West 13th Street and erected a 40-by-60-foot school they named the Crooms Academy. With Joseph at the head as principal and Wealthy by his side as vice principal, the school was the first in Seminole County to offer black students a high school education that went all the way to the 12th grade and provided a full range of subjects including music and the humanities. Hopper Academy once again became an elementary and middle school that taught up to the 8th grade and fed into the Crooms Academy. Joseph remained principal at Crooms Academy until his retirement in 1953.

Wide Influence, Living Legacy

Joseph and Wealthy Crooms were well known in Sanford beyond their radical renovations to the school system. Joseph was a talented musician and, in addition to teaching music at the school, he also gave piano lessons from his home. Many sources cite his strict expectations and tendency to rap young pianists across the knuckles for ill attention.

In 1922, the couple moved into a home at 812 S. Sanford Ave. that had been designed by the prominent local black architect Prince Spears. The front steps of the Crooms house became the traditional backdrop for the Crooms Academy’s graduating-class photos. The house was also bustling with hospitality and boarders in need of a place to stay. From school staff to homeless children, the Crooms home became a refuge for all manner of people in need. Even Zora Neal Hurston’s younger brother, Clifford Joel Hurston, lived with the Croomses for quite a while after the Hurstons’ mother died and was listed along with Howard Roberts as foster sons in Joseph’s obituary.

Joseph and Wealthy Crooms’ hard work in education wasn’t limited to Sanford. They had a lasting friendship with Mary McLeod Bethune, and Joseph co-founded the Bethune Beach Corporation, which created the only beach that black people were permitted to use in Volusia County during the first half of the 20th century. Joseph often consulted with Bethune as she grew her budding school in Daytona (now Bethune-Cookman University), and they would swap ideas on institutional education. In 1950, Joseph received an honorary law degree from Edward Waters College in Jacksonville. He died in 1957, only four years after his retirement.

Wealthy Richardson Crooms’ passion for education equaled her husband’s, and before her death in 1982 she had served as superintendent of St. James A.M.E. Church and vice-president of the Advisory Board of Bethune-Cookman College. She was awarded the Mary McLeod Bethune Medallion and received a citation from President Franklin Roosevelt for her services during the World War II years, 1941-1945.

The Crooms’ legacy of education lives on. Distinguished alumni of the Hopper Academy and the Crooms Academy include the author and anthropologist Zora Neal Hurston; U.S. Rep. Alcee L. Hastings; George Allen, the first black graduate of the University of Florida’s law school; Oswald Bronson Sr., fourth president of Bethune-Cookman University; and Bob Thomas, Sanford’s first black city commissioner.

And the legacy also continues to live on at the current Crooms Academy. The original school built by Joseph and Wealthy Crooms burned down in 1973, and the school has seen many years of hard times, but the Crooms Academy of Information Technology in Sanford is now an award-winning magnet school that focuses on the computer and technology fields and is among the top schools of its kind in the nation. Joseph and Wealthy Crooms would be proud to see how far education in their hometown has continued to evolve.