By Whitney Barrett, History Center Archivist

From the Spring 2022 edition of Reflections From Central Florida

Although you might not think of Orlando as a popular music destination, many of the great singers of jazz, blues, and gospel music passed through the city during its history. Big names such as Ray Charles, B.B. King, and Ella Fitzgerald, just to name a few, all made stops in Orlando on their way to becoming legendary artists.

Some Black singers, such as Charles, King, and Fitzgerald, got their start and rose to fame during the Jim Crow era – a time when segregation was legal and touched nearly every aspect of life in the United States. The color line was drawn in restaurants, schools, hotels, hospitals, bathrooms, water fountains – the list was endless. It even extended into the world of entertainment.

Black artists were certainly talented enough to perform in the same venues as their white counterparts, but many were not extended that opportunity. However, this did not stop the music. It led instead to the creation of what is now commonly called the Chitlin’ Circuit – a network of Black-owned venues, mostly concentrated in the South, where now-famous Black musicians performed during the Jim Crow era. According to author Preston Lauterbach, it was also called the one-nighter circuit or the theatrical circuit.

Although the origin of the term Chitlin’ Circuit can be debated, one theory links it to the food served at many venues, which included chitlins (cooked pork intestines), along with other traditional soul food dishes. Some artists have recalled that a plate of chitlins would be included as a part of the pay for their performance.

In Orlando, the circuit’s most prominent venue could be found on South Street.

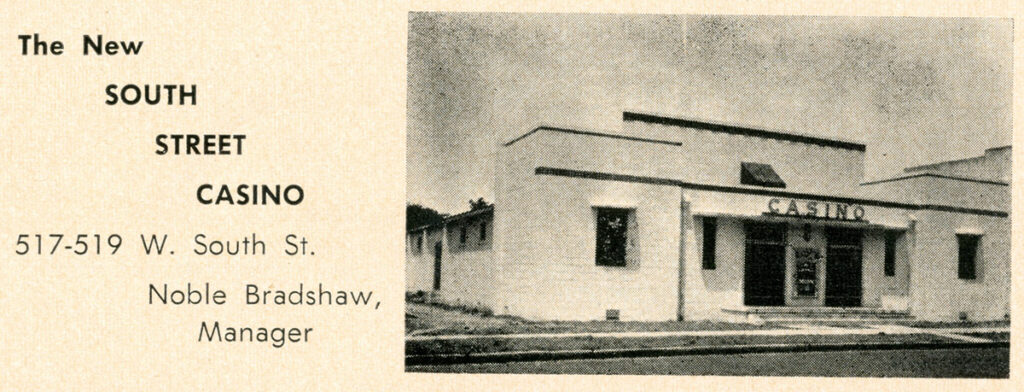

The South Street Casino

During its heyday, from the 1920s through the 1960s, the South Street Casino was a staple in Orlando’s Black community. Located at 519 W. South St., it was owned and operated by Dr. William Monroe Wells, one of the city’s first Black physicians. He also owned the Wellsbilt Hotel next-door to the casino, one of the few places in Orlando where Black visitors could stay. The importance of Dr. Wells’ contributions is significant, as he provided shelter, entertainment, and medical services to Orlando’s Black community. (Note that Dr. Wells’ hotel is now home to the Wells’Built Museum, but its original name was spelled “Wellsbilt.”)

Dr. Wells’ “casino” does not refer to a place for gambling, but a setting for social events. The South Street Casino was a community center that hosted neighborhood dances, meetings, weddings, birthdays, and even boxing matches. At one point, it even had a basketball court and a skating rink. It also became a popular stop for up-and-coming Black musicians touring the music circuit in Central Florida. Although it couldn’t compare with the Apollo Theatre in Harlem or the Royal Peacock in Atlanta, in Orlando the South Street Casino was the place to perform!

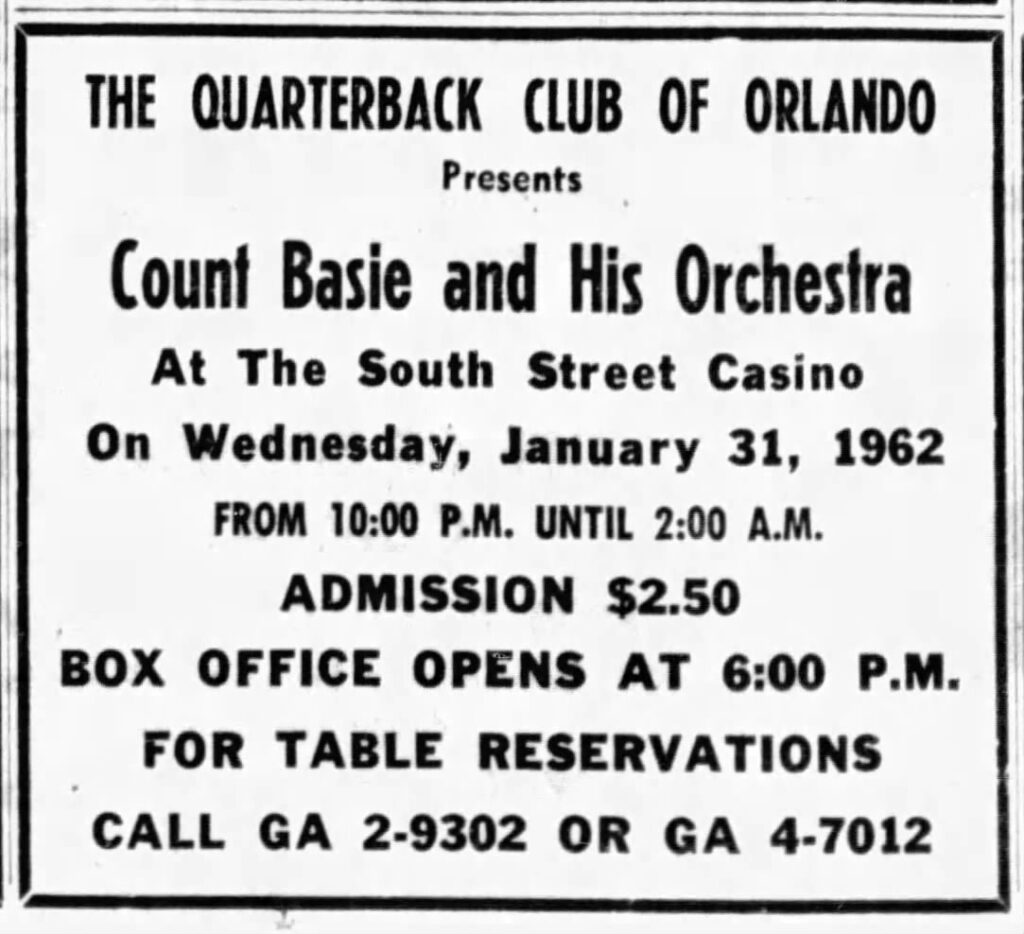

As time went on, things changed, and the Quarterback Club began to operate inside the South Street Casino. This was a private bottle club – meaning members would bring their own alcohol to drink instead of buying beverages from a bartender – that had once met at the Wellsbilt Hotel. However, after Dr. Wells’ passing in 1957, the club began to operate inside the casino.

The Quarterback Club continued to host adult dances and musical performances as part of the Chitlin’ Circuit. One 1962 ad in the Orlando Evening Star reads, “The Quarterback Club of Orlando Presents Count Basie and His Orchestra at the South Street Casino.” As the South Street Casino continued to evolve, so did its name. Eventually, the building was regularly referred to simply as the Quarterback Club. Unfortunately, the building suffered fire damage in the 1980s and was torn down. Even though it is gone, it is still remembered as a once-vital part of Orlando’s Black community.

I’ve Got a Gig to Play, But Where Can I Stay?

When musicians traveled the circuit in the South, securing sleeping accommodations was just as important as booking performances. Being on the road wasn’t always fun and music. Racism was real, and sometimes deadly. Being Black in the South in an unfamiliar area could prove to be a dangerous situation if travelers were not careful.

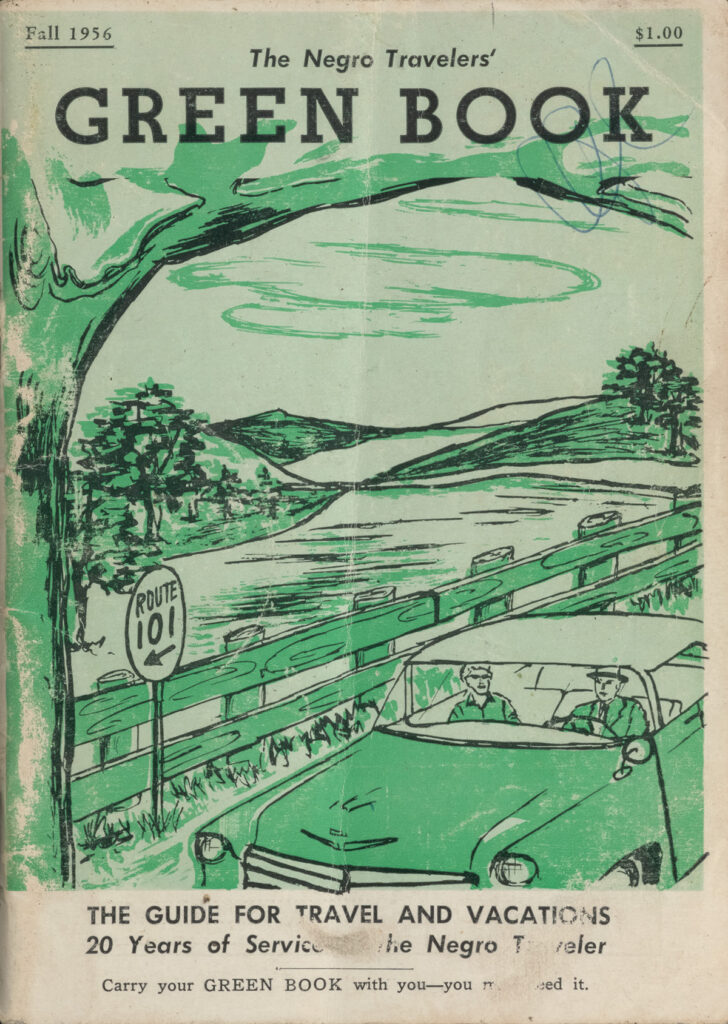

In search of information and safety, many Black travelers turned to The Negro Motorist Green Book – a

guidebook listing hotels and restaurants that would cater to them. Although author Victor H. Green’s first edition, published in 1936, focused on New York City, the Green Book soon expanded to cover other states. The 1956 edition included two listings for Orlando: the “Wells Bilt Hotel” and the “Sun-Glo Motel.”

The Sun-Glo was located at 737 S. Orange Blossom Trail, near Jones High School. It opened around 1955 and added 16 apartment units the following year. Its motto was “A Highway Hotel Catering to the Elite Colored Clientele.” As hotel receipts in the History Center’s collection make clear, many famous performers stayed there. However, unlike Dr. Wells’ hotel, the Sun-Glo was white-owned and operated. Franklin James Manuel, owner of the construction company Manuel Builders Inc., ran the hotel until about 1970. The building still stands and is currently home to the Orange Inn Motel.

The End of an Era

Eventually, Black performers were allowed on stage in other venues in Orlando. Unfortunately, Jim Crow still reigned and the audience remained segregated. In 1957, Louis Armstrong performed at Orlando’s Municipal Auditorium (later transformed into what is now the Bob Carr Theater); an Orlando Sentinel ad noted a “Reserved section for White and Colored.” Two years later, another Sentinel ad from June 1959 for a Mahalia Jackson concert at the auditorium reads, “Seats for White and Colored.”

The passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act ended the segregation of public spaces. This allowed for increased opportunities not only for artists to perform but also for Black people to attend more shows. With public spaces becoming generally more integrated, the need to seek out Black-only hotel and performance spaces waned. Although many of the clubs and venues where Black artists performed are no longer around, the influences of the musical talent who walked through their doors can still be heard today.