Pinkey in patriotic garb

By Joy Wallace Dickinson

The World War II years meant tough times for Central Florida, as they did across the United States. Residents worried about loved ones in uniform, fighting in Europe or the Pacific, and coped with rationing and food shortages, making do with less. During such times, even small things that make us smile mean a lot, and in Orlando, folks could count on a little fox terrier named Pinkey to bust through the gloom.

She was Orlando’s “Most Stylish Dog,” an Orlando Evening Star headline proclaimed in September 1940, when Pinkey was 13 months old and already sported quite a wardrobe. The pup’s owner, Daisy “Day” Murr of 57 W. Pine St., had outfitted Pinkey with 10 dresses, 5 ballet costumes, 14 hats, and 5 baskets, in colors to match the ensembles. Three years later, in 1943, the petite canine’s collection had ballooned to 40 dresses, 15 ballet costumes, and 30 hats, plus more baskets. By this time, almost two years after the United States entered WWII, Pinkey drew praise for her patriotism. She appeared in her Uncle Sam costume at events around town, doing “more than her share in the selling of war bonds,” a 1943 news story reported.

Pinkey in patriotic garb

“A dancing dervish”

Whether decked out in red, white, and blue or her ballet costumes, Pinkey seemed to be always in motion. In addition to the usual canine tricks such as sitting up, the little terrier could jump rope, leap through hoops, and whirl around on her hind feet “like a dancing dervish,” according to the 1940 article. Daisy Murr had trained the little dog to be quite a dancer. Perhaps Pinkey’s most unusual costume paid tribute to Sally Rand, the burlesque fan-dance queen who had become a household name. Rand had created a sensation at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, where millions watched her twirl to the music of Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” as she swirled huge ostrich-feather fans around her body in a graceful game of peek-a-boo.

The sensational Rand might seem a strange choice as a muse for Pinkey in 1940, rather than, say, Shirley Temple or Scarlett O’Hara. But Murr was a maverick – “probably pioneer Orlando’s most colorful, talked-about, entertaining and likeable” personality, according to Orlando Sentinel columnist Jean Yothers. No doubt she “had shocked some staid pioneer citizens with her comments and life style,” Yothers wrote in 1973. Daisy Murr was “a real pistol in her day.”

A young Daisy Huffstetler Murr

Thanksgiving arrival in 1884

Murr was born Daisy Huffstetler on Jan. 13, 1883, in Henry, Tennessee, and came Orlando in 1884 with her widowed mother, Bell, and her older brother, William I. “Bill” Huffstetler. The family was fond of holidays. Bill was born on the Fourth of July in 1876 – the nation’s centennial year – a patriotic birthday that Murr claimed for Pinkey decades later. Thanksgiving was important to them, too. The Huffstetlers had arrived in Orlando by train on Thanksgiving Day 1884 when Bill was 8 and Daisy was a just year old.

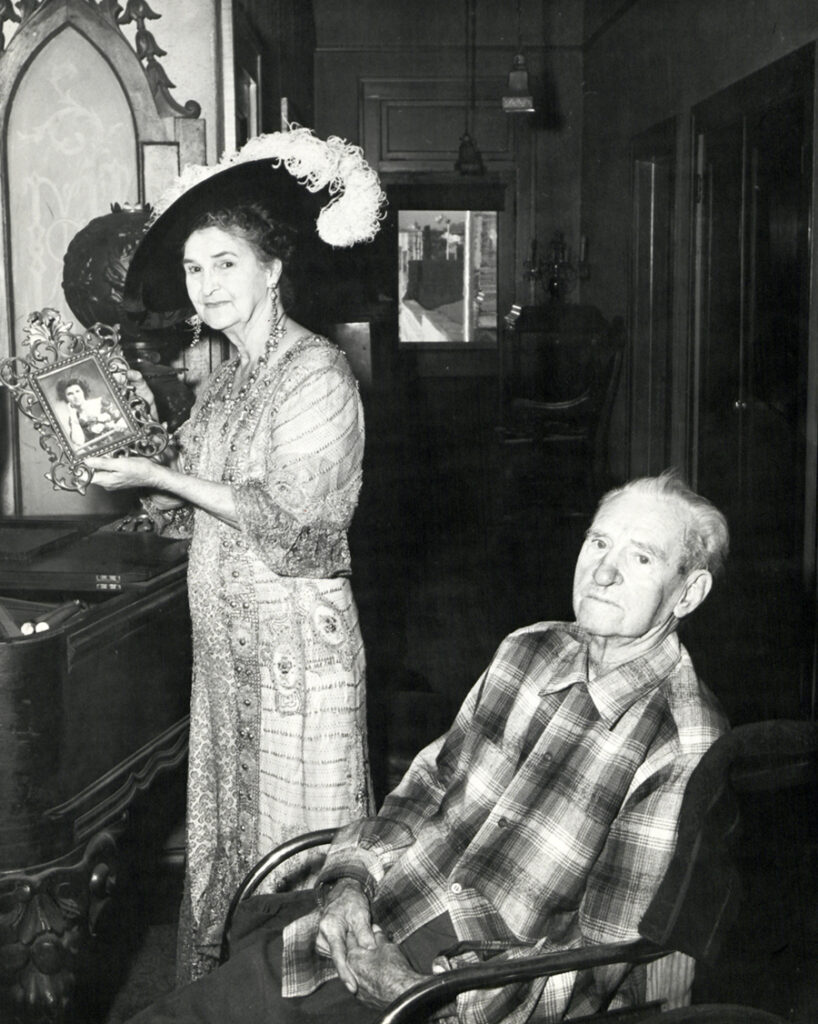

Their mother bought a 16-room house on West Pine Street, and the family operated it as a boardinghouse until 1926. Nothing stood between the house and the railroad tracks except grass, where the Huffstetlers pastured cows. In the late 1890s, young Bill Huffstetler traveled the country as a competitive bicycle racer. He eventually settled in the young city of Miami, where by 1915 he was at the helm of a successful boat yard and rubbed elbows with Astors and Vanderbilts, he later told Sentinel writers. By 1940 he had moved back to Central Florida and by 1954, when he was 78, he was living with his sister at her Pine Street digs, close to the spot where he had grown up – a spot that his sister, Daisy, had never left, as Orlando grew around it.

Daisy Murr dressed for a pioneer-themed celebration

A shocking beauty

By the time she was in her late 50s and training Pinkey, Daisy Murr had cut a memorial figure in Orlando lore. In her youth especially, she had been “a great beauty,” with “raven hair, snapping black eyes and a peaches and cream complexion,” Jean Yothers recalled in her Sentinel column. Longtime residents remembered Daisy riding down Orange Avenue daily in a buggy pulled by high-stepping white horses. By her side sat a little dog – a precursor of Pinkey.

Murr’s contemporaries also recalled a dramatic sense of color and style. One day, Daisy would be dressed all in black and white, with matching black plumes in her hat, and the next day she might be all in green, or pink. As she passed, heads turned. “The men would stop stock still, like Lot’s wife,” recalled Orlando pioneer Roberta Branch Beacham in 1942, in one of her humorous letters to the Sentinel signed “Beulah Backwoods.” If the men stared, the women would stick their noses in the air and pretend they hadn’t seen Daisy at all, Beacham wrote.

The beautiful Daisy Murr “had plenty of money” in those early years of the 20th century, friends told a Sentinel writer decades later, in 1978. At a young age, Murr had taken over her mother’s role of “landlady” at the boardinghouse and later she had an antiques business. After Murr’s death in 1973, she left an estate worth about $145,000 – around a million dollars today. Yothers praised her for her generosity and charitable support of “every worthwhile cause in town.”

Besides her looks and her money, Daisy Murr inspired rumors because she was way ahead of her time, by at least 50 years, according to her friends. She wore plenty of makeup, sported a pretty spicy vocabulary, and smoked in public, which was verboten in her youth for women, especially before the 1920s – not because of it was bad for your health (that news was still years in the future), but because it was considered unladylike.

In June 1902, when Daisy was 19, she had married a fellow named William Edwin Murr, but the marriage didn’t last long. In June 1919, she petitioned the circuit court to be able to control her own property, something that as a married woman she wasn’t automatically able to do at the time. Judge C.O. Andrews granted her petition on October 31 and deemed her a “free dealer” in every respect. By the 1930s, she had an antiques business at her home address, which was upstairs over a commercial space on Pine Street. “A wonderful collection of old glassware and China. Call and look them over,” she advertised in the Sentinel in 1934.

Daisy Murr and Bill Huffstetler, surrounded by antiques at 57 W. Pine St. in Orlando

Pinkey on parade

A few years later, in 1939, Murr brought to her Pine Street apartment the fox terrier pup she named Pinkey – a popular feminine nickname into the 1930s, with varied spellings, that was sometimes used for boys and men, too. Perhaps history’s most famous “Pinkie” was the portrait of a young woman by the English painter Thomas Lawrence, often paired in home décor starting in the 1920s with Thomas Gainsborough’s “The Blue Boy.”

It took Daisy Murr 10 months to train Pinkey, as she gathered costumes and began showing off the dog’s achievements to friends and visitors to her shop in 1940. Pinkey could retrieve a toy on command from a lineup of more than 30, Murr told reporters, and could also run errands – or at least one, to buy cigarettes. Murr would send Pinkey to a nearby store, carrying a basket with a little purse. A store clerk, in on the trick, would put correct change in the purse, place Murr’s cigarettes in the basket, and send Pinkey trotting back home. Murr didn’t “allow Pinkey to do this too often for fear she might be picked up by a passerby,” she told one reporter in 1943.

Plenty of passersby on downtown streets spotted Pinkey during the WWII years, as the terrier accompanied Murr on strolls and to events, including popular pioneer-themed parties at which longtime Orlandoans donned 1890s costumes and regaled reporters with stories of the days when they and the City Beautiful were young. In April 1942, a three-day celebration marked a century since the arrival of the first documented homesteaders in the area in 1842. Roberta Branch Beacham’s “Beulah Backwoods” persona proclaimed herself the “best-lookin’ gal” in the parade – except for Daisy Murr, who was accompanied by Pinkey.

That 1942 parade took place at a time when Orlandoans had to give up many good things that their pioneer forebears never had, a Sentinel editorial writer noted. If Hitler were to prevail, Americans would be taken back to a harder life than even the pioneers knew, but our country would not let Hitler win, the editorial said. As soon as the centennial celebration was over, city leaders would unveil a new drive to sell war bonds – one of Pinkey’s specialties as an inspiration for patriotism.

Sadly, the little pooch didn’t make it see Orlando celebrate victory in World War II in 1945. On June 21, 1944, the Sentinel reported the death of the little dog “who was so well trained she was just about human. In fact, some people even gave her credit for having much more sense than the average human.” The cause of death had been a stomach condition, the story noted, adding that Pinkey would be missed by many Orlandoans who had delighted in seeing her at shows and parades, dressed in a wardrobe that looked “like that of a star.”

Pinkey’s owner, Daisy Murr, knew something about cutting a fine figure. She was 61 when Pinkey died in 1944, and she lived almost another three decades, dying at 90 in 1973, five years after her brother, Bill, who died in 1968. Into the 1960s, when news writers needed a holiday feature around Thanksgiving or July 4, they might visit Daisy and Bill in their antiques-packed home next to the Trade Winds Cafeteria on Pine Street, which stood on the site of the siblings’ old home. Daisy would give the visitors homemade guava jelly, and Bill would regale them tales of arriving in Orlando on Thanksgiving Day in 1884 and landing smack in a patch of sandspurs. The stories the reporters wrote never mentioned a successor to Pinkey, the little dog Daisy Murr trained to bring smiles to Orlando during dark war times. Pinkey was one of a kind, and a real trouper.

Pinkey in one of her ensembles

Note: These photos are from Daisy “Day” Huffstetler Murr’s scrapbook in the History Center’s collection. In her adult life, Murr often used “Day” as her first name, in city directories and ads for her antiques business. Friends seem to have called her either Day or Daisy, which we’ve used in this article.