By Chris Madrid French from the Winter 2017 edition of Reflections magazine

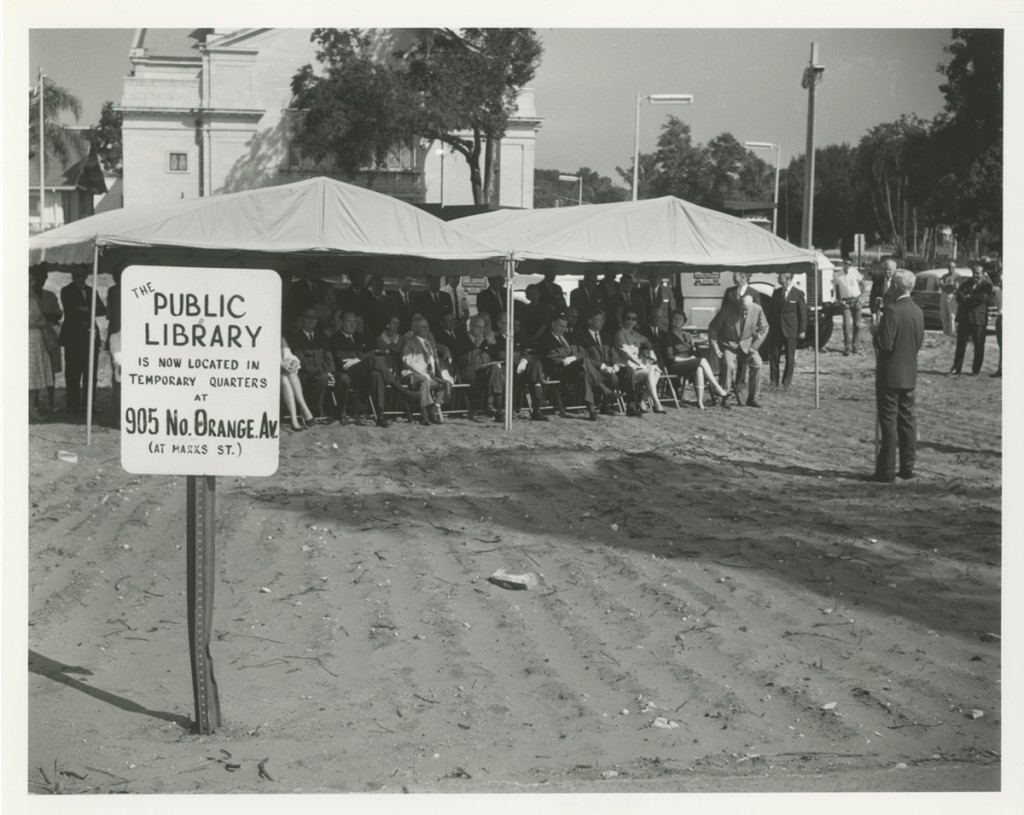

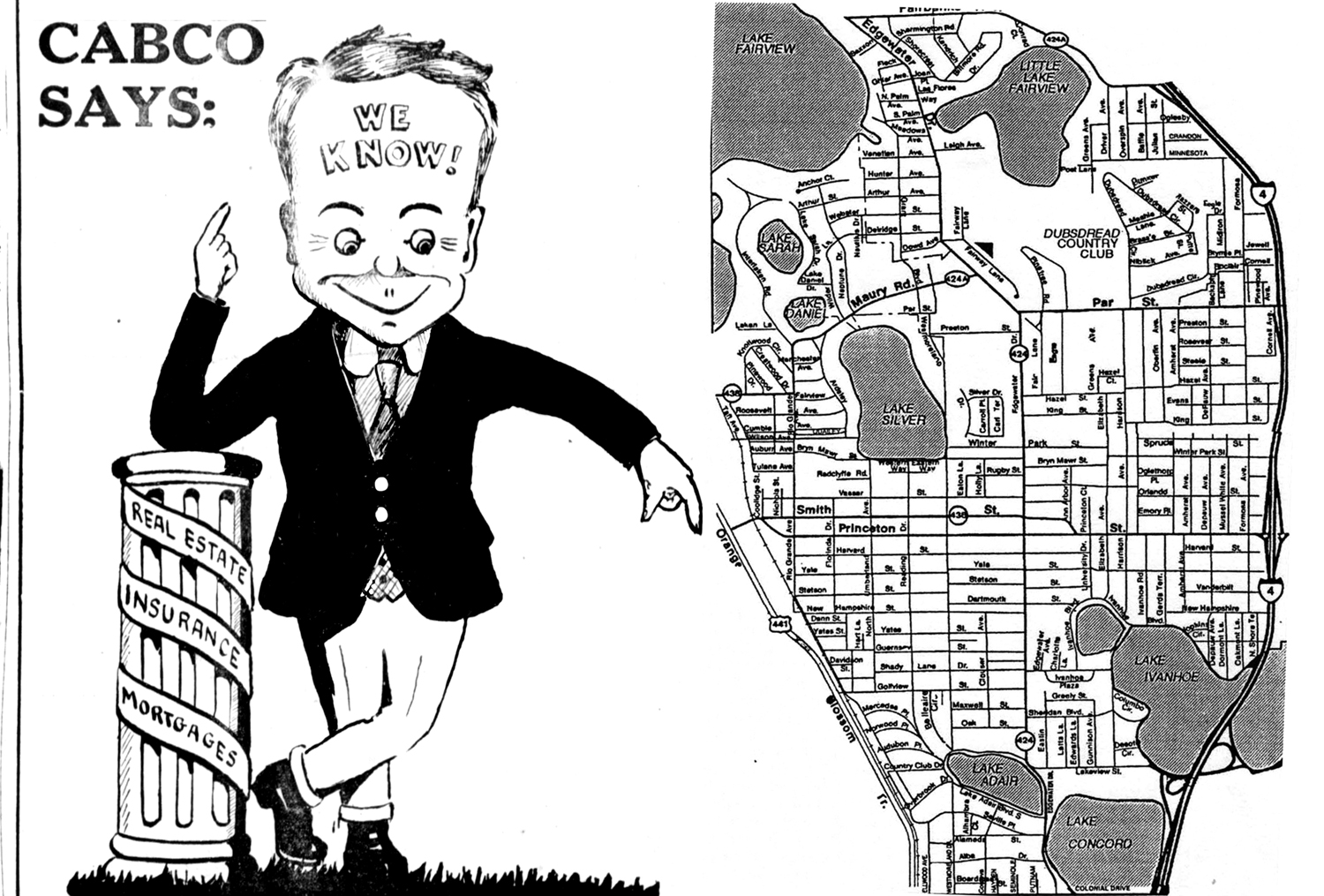

When I first moved to Orlando from San Francisco in 2011, a neighbor mentioned that I should visit the “ugliest building” in town. Despite her warnings, I knew I had found an architectural treasure when I laid my eyes upon the enormous, striated concrete structure she had mentioned. In 1962, the citizens of Orlando passed a Civic Improvements Bond issue that provided a million dollars to replace the Albertson Public Library, a Neoclassical-style structure that opened in 1923. For the new building, at the corner of Rosalind Avenue and Central Boulevard in downtown, the city selected the Connecticut-based architect John Johansen (1916-2012) to create a signature design that represented an expansive new era in Central Florida. Johansen was one of the “Harvard Five,” influential architects who studied with Walter Gropius, himself a pioneer in modernism and the founder of the Bauhaus, a significant design school in 1930s Germany.

A bold architectural concept

Johansen specialized in Brutalism, a bold architectural concept featuring unfinished concrete for interior and exterior surfaces. The name originates from the French term beton brut, in a reference to the “raw” or unpainted nature of the concrete. A Brutalist building is basically constructed in the same way as a sandcastle, using rough wood boards as “formwork” to hold the poured concrete. When the material dries, the wood is removed, leaving patterns, striations, and markings of the organic material on the walls, stairways, and ceilings.

For the Orlando Public Library, Johansen conceived a series of concrete towers and boxes held in position at various heights by strong piers. The building featured rough-hewn cedar patterns embedded in its poured-concrete walls, surrounding an interior open space with a rooftop patio overlooking nearby Lake Eola. Martin Van Buren of North Carolina worked as interior design consultant, while local architect Robert Murphy coordinated the design and construction process with Johansen, who lived in New Canaan, Conn. (Murphy is perhaps best known for his firm’s 1963 concrete “Round Building,” which once stood on the grounds of what’s now the Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts.) At the completion of the new library, director Clara Wendel lauded the building, noting that it “has had an emotional impact on the city unmatched by any structure in its history” (Library Journal, 1966).

Expanding in the 1980s

Johansen’s library was envisioned as the first stage of a main library for Orlando and Orange County; future additions were planned as part of the original design. When the library’s needs outgrew the poured-in-place Johansen structure (finished at a mere 60,000 square feet), voters approved a $22 million bond issue in 1980 that also created the Orange County Library System and provided funds for a 230,000-square-foot addition to the Orlando Public Library, which became the main branch of the system.

The library’s expansion was planned in a style similar to the existing building – all concrete, from the floor to the roof, and in prime Brutalist form. Designed by local firm Schweizer Incorporated, it opened in April 1986 and has since undergone a series of interior renovations, while keeping the original style of both buildings intact. At the grand opening, L. Duane Stark, lead design architect for the project at Schweizer, observed that “the building projects the image of a well-studied piece of life-scale sculpture, and few who see it remain unmoved.” The enormous structure, which now fills an entire city block, is a remarkable representative of a restored, lively Brutalist design that continues to captivate – and sometimes confuse – the public.

“Like a death in the family”

Unfortunately, the expansion and restoration of the Orlando Public Library is the exception and not the rule for historic Brutalist structures. Johansen’s work has been taking a beating for decades. Way back in 1988, not long after the expansion of Orlando’s Johansen-designed library opened with great fanfare, television talk-show host Phil Donahue purchased and demolished Johansen’s one-of-a-kind Labyrinth House in Westport, Conn., calling it an “avant-garde bomb shelter” that collected fast-food wrappers and “lovers and other strangers at midnight.”

Built in 1966 for Dr. Howard Taylor, the 3,100-square-foot concrete house was known for its “juxtaposition of surfaces” and textural contrasts between the interior and the exterior. Willis Mills, then president of the Connecticut Society of Architects, defended the site as “a seminal work by one of America’s most original and creative architects.” When told of Donahue’s architectural misdeed, Johansen replied, “It’s like a death in the family. Mr. Donahue has a right to his taste, but ownership is a responsibility and not a power over everything.”

Johansen, who died in 2012 at the age of 96, never understood the destruction of his buildings. Why would one destroy art? He did provide solace to preservationists with these words, however, inscribed on his website: “The reward is in the doing; I won already for having created it. I offer finally a more forceful reference: forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

Architectural design is cyclic; an entire generation of Americans went to school, read books, attended church, paid their traffic tickets, and served on juries in Brutalist buildings across the country. Saving these buildings is about more than keeping a structure upright; it is also about saving people’s stories and understanding our own contributions to history.