By Tana Mosier Porter From the Spring 2024 Edition of Reflections Magazine

Little is known about the four handwritten ledgers that make up the City of Orlando Building Permit Collection held in the Brechner Research Center at the Orange County Regional History Center. A 1986 donation from the city government to the Historical Society included these ledgers containing the names of people who applied for building permits between 1906 and 1947. Permits predating these ledgers remain a mystery.

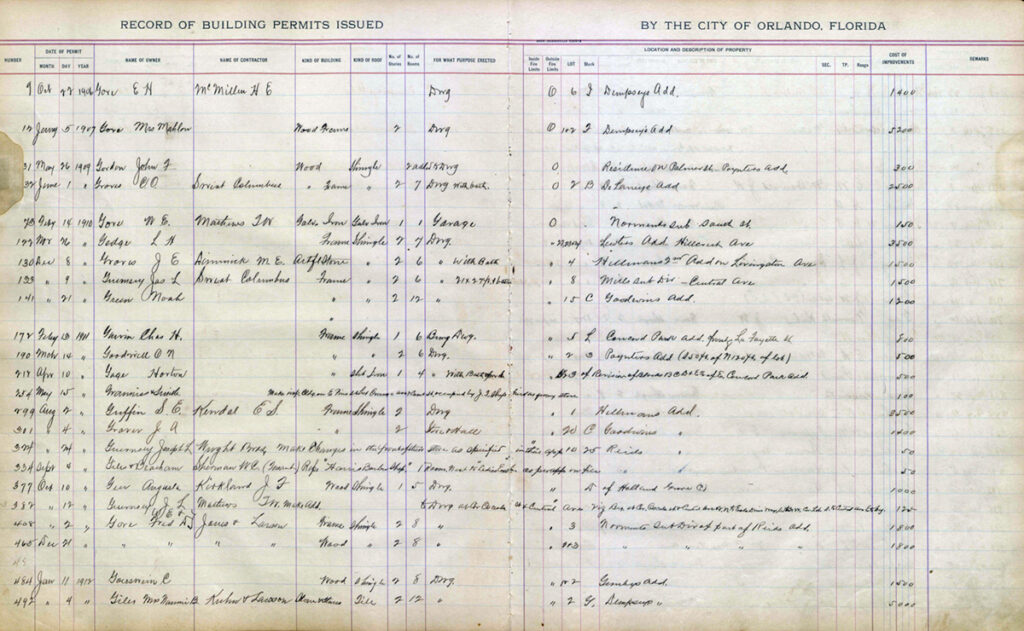

The handwriting reveals that only a few people wrote in the books. The names listed include numerous locally known African Americans, which indicates that Black residents could acquire building permits, but in those days racial segregation kept them from entering the same office or writing in the same book as white residents. Additionally, the organization, in sections by the letters of the alphabet, suggests an attempt to index the information. Within each section, the names, though they begin with the designated letter of the alphabet, are listed by date, not alphabetically.

All this suggests that a city employee sorted each day’s permits alphabetically and numerically and entered them into the ledger. The employees made mistakes and omitted information. The applicant was not there to assist or correct them. Their handwriting, often hurried and frequently nearly illegible, makes reading the entries difficult. They used “ditto marks” copiously, sometimes leaving in question whether they meant “the same as above” or “eleven.” But with all those faults and all that mystery, these recordkeepers left us an informative and fascinating primary resource.

A transcription effort currently underway at the History Center will resolve some of the mysteries and correct some of the errors, while replacing the cursive handwriting in the old ledgers with typewritten entries in a digital resource. The kind of problems encountered in the work appear in the ledger page reproduced above, from the letter G in Book One, which begins with a permit issued to E.H. Gore in 1906. It’s the earliest in the book, which ends with 1920.

The random numbers in the first column could refer to the number of the building permit itself, but that can’t be proven since the actual permits no longer exist; they were presumably lost in a spectacular 1973 fire at the city’s Health Department. The Building Permit Books survived, perhaps because they were saved from the fire or because they were stored elsewhere – allegedly in a shed at Tinker Field, Orlando’s now-gone baseball stadium. Book One has suffered moisture damage consistent with a fire or inappropriate storage.

Reading across, the next group of three columns provides the date of the permit. Most permit research focuses on determining the age of the structure, making this perhaps the most important information.

The third column, also important, contains the name of the property owner who applied for the permit. In this troublesome column, the names are often unclear due to misspelling or difficult handwriting. A search through city directories, though time-consuming, usually clarifies the applicant’s name, and when the directories fail, the Orange County property records sometimes help, but some names remain forever uncertain. In the case of an early Seventh-day Adventist Church, only the 1919 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map in the Brechner Research Center confirmed the name. Bracketed question marks indicate unresolved issues. In the example at left, city directories confirmed the names Augusta Geis on line 377 and C. Goesswein on line 484 as property owners.

The fourth column indicates the name of the builder or contractor on the job. These often-unreadable names, though interesting, are not vital to the record. On line 32 of the page at left, Columbus Sweat was indeed the contractor’s name.

The next five columns – Kind of Building, Kind of Roof, Number of Stories, Number of Rooms, and For What Purpose Erected – are occasionally filled out properly, but they are often skipped entirely and sometimes are filled with material that would seem to belong on the building permit itself. This material, including unfamiliar abbreviations, usually appears written across all of the spaces, as shown by lines 254 and 324 of the ledger page.

The column noting a building’s purpose contains the most interesting information. It normally designates a residence or dwelling, but other interesting structures often appear in this column, including churches, schools, and businesses. Social changes become obvious here. Bungalows appeared about 1911, along with houses built to be rentals. Most listings employed frame construction, with occasional brick or concrete, but roof materials varied. Some houses had only one room, though more commonly two or three. In the mid-teens, people began adding bathrooms to existing houses and then including them in new construction. Sleeping porches became popular additions. About 1919 garages replaced barns as people acquired automobiles.

In the last columns, property descriptions showing the expansion of the city into new territory often present a problem. Bracketed question marks appear here frequently. But the county property records usually verify the name of the development and also whether it is an addition or a subdivision. Many of the earliest cited Reid’s Addition, a downtown platting, and later other builders’ subdivisions of part of Reid’s. And later still, numerous permits named locations in Concord Park, a large development along Colonial Drive. Some applications, especially the earliest, include the surveyor’s description of sections, quarter-sections, and measurements. The descriptions are often difficult to follow and transcribe properly, while separate columns for Section, Township, and Range mostly remain unused.

The final column records the cost, almost universally incorrect according to contemporary sources. Newspaper announcements of coming construction nearly always show much higher costs for the work than what appears in the permit application.

This is Book One, for the years 1906 to 1920. Book Two covers 1921 to 1925 and details construction during the Florida Land Boom. Book Three, 1926 to 1937, documents the Great Depression, and Book Four, 1938 to 1947, includes postwar growth.

Taken together, they provide a valuable resource for understanding the urbanization process during four early decades in Orlando’s history.