By Rick Kilby from the Spring 2024 Edition of Reflections Magazine

Who Was Commodore Rose in Pioneer Florida?” reads a February 1975 headline for Marian Godown’s “Here’s Florida” feature in the Fort Myers News-Press. Godown invited readers to take a quickie quiz: was the Commodore the owner of a steamboat line, an “ex-Yankee” steamer captain, or a Black “steamboat stewardess”?

The last choice was in fact the answer. Commodore Rose’s tale is one of the few known stories of countless formerly enslaved people who found their freedom via the tannin-stained waters of the St. Johns River. Sadly, the histories of people of color have, until recently, been largely ignored, whereas a good deal more has been written about Rose’s former owner, Captain Jacob Brock (sometimes spelled Broch).

While Godown and others have written about “Commodore” or “Admiral” Rose in more contemporary media, just two primary accounts about Rose survive from the period in which she lived – the 19th century. One was written by Harriett Beecher Stowe, the famed author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, who had a winter home in Florida.

“When the magnolia-flowers were beginning to blossom, we were ready, and took passage – a joyous party of eight or ten individuals – on the steamer ‘Darlington,’ commanded by Capt. Broch, and, as is often asserted, by ‘Commodore Rose,’” Stowe writes in Palmetto-Leaves, a collection of articles published in 1873. “This latter [Rose], in this day of woman’s rights, is no mean example of female energy and vigor,” comments Stowe, whose articles were designed to encourage her sympathetic northern readers to visit and perhaps even relocate to the Sunshine State.

The second mention of Rose appears in author Ledyard Bill’s 1869 travel guide, Winter in Florida, in which Bill observed that Captain Brock may have sailed the boat, but “Admiral Rose” was in actual command. “Her every word of command might be heard ringing out sharp and clear above the noise and confusion at every landing,” Bill writes, concluding that Rose’s orders were “instantly executed by every officer below captain.”

A strong supporter of the Union cause, Bill moved from Louisville, Kentucky, to New York at the start of the Civil War. He later relocated to Massachusetts, where in addition to publishing and writing he became active in politics. Both Stowe and Bill were northern abolitionists who had incentive to promote Rose’s larger-than-life persona.

The Cussin’ Captain

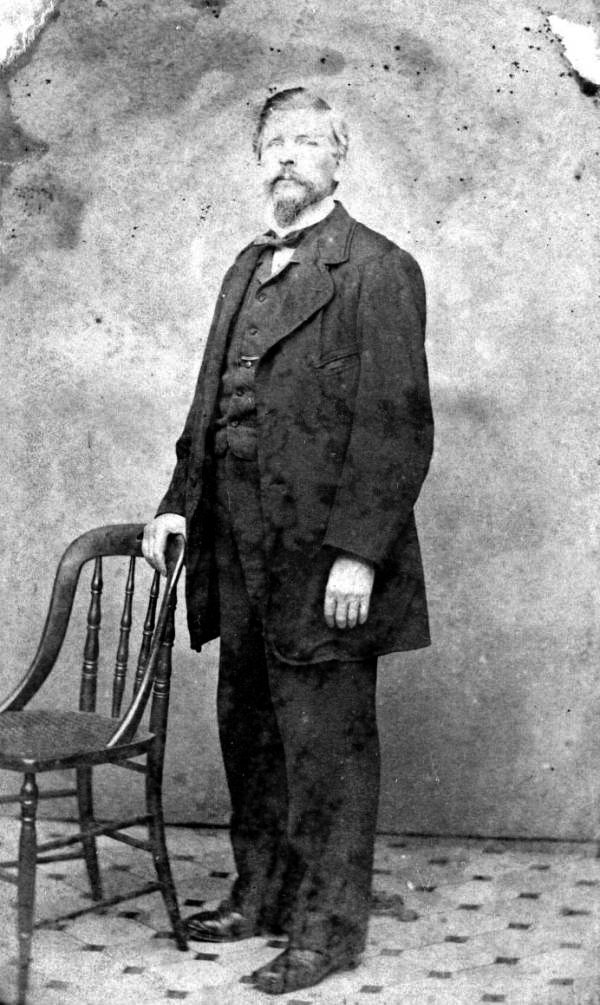

While Rose is only mentioned in these two books, 19th-century descriptions of the Darlington’s captain, Jacob Brock, are common. Today he is often portrayed as one of the founders of the historic Central Florida town of Enterprise and a pioneer in tourism on the St. Johns River. Colorful depictions of Brock often note that he was short in stature and displayed an affinity for foul language. He delighted in startling his passengers with a surprise blast of the ship’s steam whistle while engaging them in story.

Born in Vermont and raised as a “river rat” on the Connecticut River, Brock spent his early adult life in Hartford, Connecticut, where he operated a machine shop, according to Volusia County historian Lani Friend. A critical travelogue called Letters from the Slave States asserts that Brock worked as an “engineer plying the Charleston waters” in South Carolina before “scraping together a few dollars” to purchase a “small, worn-out steamer.” The author of this biased book, published in London four years before the start of the Civil War, notes that Brock had “no qualms on the subject on ‘involuntary servitude’ always providing that it pays.” One of Brock’s passengers left a more forgiving testimonial, noting that he was a “rough spoken man, but a kinder-hearted or more genial man never walked a deck or told a story.”

The Richland Explosion

In her narrative about Rose in Palmetto Leaves, Stowe disclosed that Rose was once a slave owned by Captain Brock who had been emancipated for her “courage, and presence of mind, in saving his life in a steamboat disaster.”

It could have happened when Brock captained the steamer Richland on South Carolina’s Pee Dee River, transporting freight between Charleston and Cheraw, an important hub in the production of cotton. According to newspaper accounts, both of the Richland’s boilers exploded and the boat caught fire, burning to the “surface of the water” on Jan. 14, 1849. Boiler explosions on steamboats were so commonplace in the decade between 1830 and 1840 that after nearly 2,000 deaths, the United States Congress passed an act mandating inspection of steamboat boilers “to provide better security of the lives of the passengers.”

Casualties on the Richland may have risen as high as 15 and included both white passengers and the Black crew. Brock was in the pilothouse when the explosion occurred but survived due to the “exertions” of a stewardess, according to news reports.

A ship’s steward, or in this case stewardess, was a crew member who served the needs of guests and crew as well as ensuring the vessel was clean and orderly. Black workers, both free and enslaved, often served in various roles on riverboats. It is quite possible that Rose was the Richland crew member who pulled Brock to shore after the 1849 explosion in these accounts.

The Steamer Darlington

Brock had a new vessel before the end of that year, and newspaper advertisements pronounced that the captain would transport any light freight up the Pee Dee River aboard the “new light draught steamer DARLINGTON.”

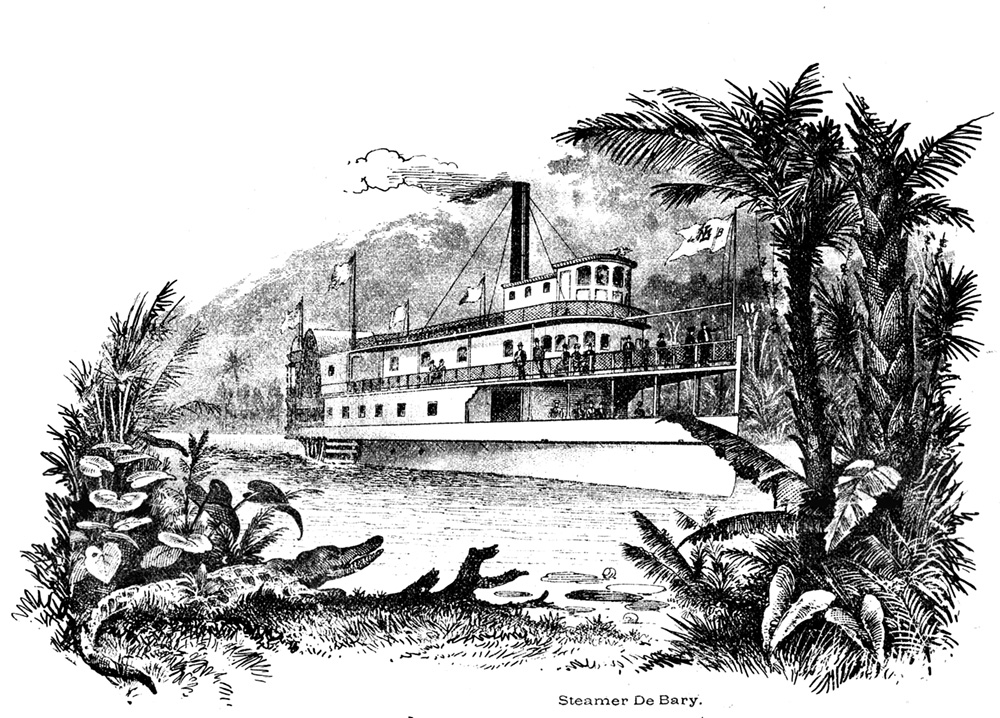

Built in a Charleston shipyard, Brock’s new vessel initially hauled cargo between Charleston and Cheraw. It was a sidewheel steamer made of wood that could hold up to 40 passengers on the upper deck. There were two saloons onboard for passengers, the larger of which doubled as a dining room. By 1853, the Darlington initiated service transporting passengers and goods between Jacksonville and Palatka on the St. Johns River.

An 1854 advertisement in the Charleston Daily Courier announced that Captain Brock was commencing service to Enterprise on the north shore of Lake Monroe and “all the intermediate landings on the St. Johns” from the towns of Palatka and Welaka.

According to Volusia: The West Side, Brock purchased land in Enterprise in 1852 and by 1855 built a substantial steamboat wharf on the north side of Lake Monroe, where he would also build his hotel, the Brock House. “Captain Brock foresaw the possibilities of tourist travel for the little-known lands about Lake Monroe,” write authors James Branch Cabell and A.J. Hanna in their 1943 volume, The St. Johns: A Parade of Diversities, and he built a “neat inn for the entertainment of his steamboat passengers.” The comfortable New England-style hotel opened for guests in the winter of 1856. The wood-frame building was as far south as many Gilded Age visitors would venture into Florida, and Brock’s steamboats were initially the primary transportation to this still untamed part of the state. Brock owned the hotel until 1876.

Over the years the Brock House would be expanded and host presidents (U.S. Grant and Rutherford B. Hayes), Vanderbilts and Rockefellers, and even artist Winslow Homer. Guests were well taken care of by Black porters, maids, and cooks, many of whom lived in nearby Garfield, a Black community composed of formerly enslaved people. The town slowly disappeared after the great freeze at the end of the nineteenth century that wiped out much of the region’s citrus, but the population of freedmen and women was at one time larger than that of Enterprise, according to the Enterprise Museum.

Slavery in East Florida

People fled slavery at South Carolina and Georgia plantations in the 18th and early 19th centuries, knowing that they might live free in La Florida when it was under Spanish rule. Fort Mose, established in 1738 by formerly enslaved people, was the first free Black community in North America. However, during Florida’s two decades of British rule from 1763 to 1783, plantations arose along the St. Johns River that utilized enslaved individuals as labor. Two well-known Central Florida examples include the Beresford plantation, which famed naturalist William Bartram visited in 1766, and the Spring Garden plantation at what is now De Leon Springs State Park.

During the Seminole Wars (1816-1858), Black people who had escaped slavery in Florida joined Seminoles to fight against U.S. military forces and white settlers. These Black and Seminole forces overwhelmed five plantations along the St. Johns River, freeing the enslaved laborers who then also united with the Seminoles. Perhaps as many as 300 enslaved people were liberated from the Spring Garden plantation.

As part of the Public History Research Collective led by Stetson University’s visiting assistant professor of history Andy Eisen, incarcerated researchers from the Tomoka Correctional Institution in Daytona Beach discovered new information on enslavement at Spring Garden. The project unearthed the names of more than 230 people who were enslaved at Spring Garden in the mid-1800s and, in 2021, produced an exhibition, “Slavery and the Struggle for Freedom in East Florida,” that listed those names.

The collective’s work also documented that the plantation’s last owner, Thomas Starke, enlisted Jacob Brock to transport enslaved individuals. Historian Lani Friend’s research revealed that between 1856 and 1858, Brock transported 33 enslaved people between the ages of 6 and 50 between Savannah and Jacksonville. The 1860 Slave Schedule for Volusia County shows that Brock also owned 11 unnamed enslaved individuals, including a 40-year-old woman that could possibly be Rose.

The River Calls to Freedom Seekers

Florida entered the Union in 1845 as a slave state. In her book Slavery and Plantation Growth in Antebellum Florida, 1821–1860, Julia Floyd Smith asserts that enslaved people escaped from Florida by “traveling east along the St. Johns River to Jacksonville, where they boarded a vessel heading for a northern port.” She notes than in 1854 an act was passed “to provide for the regulation of vessels in the St. Johns River area and to insure a more diligent search for runaway slaves.”

When the Civil War began in 1861, Florida was the third state to secede. Its population was about 140,400, of which 44 percent were enslaved. Although Brock was born a northerner, he had made his fortune in the South, and he had a significant financial commitment in Florida. As a result, the captain allowed two of the four steamboats in his fleet, the Darlington and Hattie, to be utilized by the Confederacy.

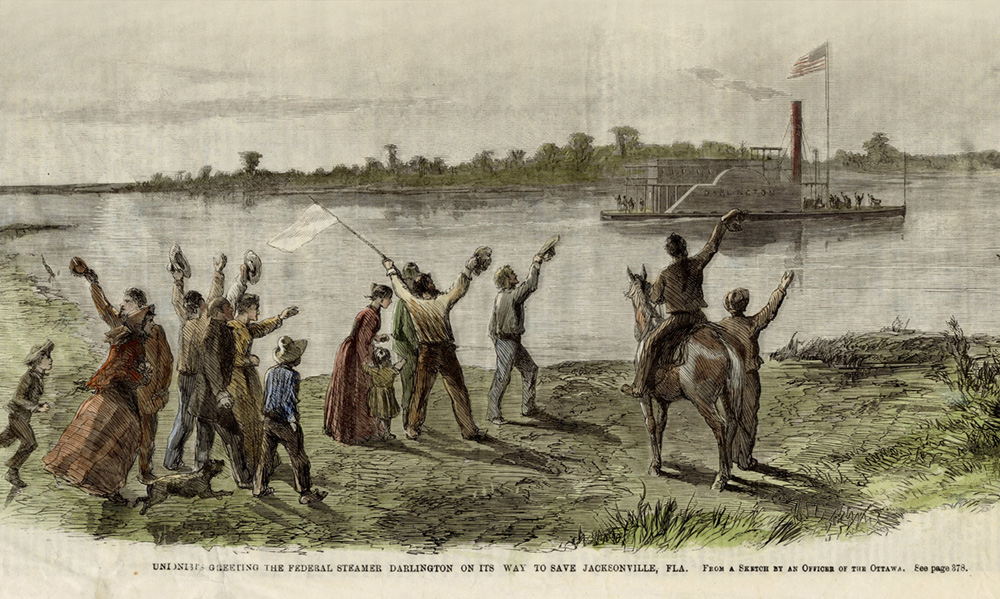

Brock was at the helm of the Darlington, helping to evacuate residents of the north Florida town of Fernandina before Union troops arrived in 1862 when he was caught by Federal forces. “There were passengers, including women and children, aboard the Darlington, and yet the brutal captain suffered her to be fired upon, and refused to hoist the white flag notwithstanding the entreaties of the women,” read the Union officer’s report published in northern papers, “I send the Captain of the steamer home a prisoner,” the officer wrote. Brock spent the remainder of the war in Union prisons.

Transporting Freedmen and Freedwomen

After the war’s conclusion, Brock regained his two captured steamboats and resumed operations on the river. Ironically the decks of the Darlington, once used to transport enslaved people to Florida, were now used to transport the newly emancipated to the Freedmen’s Bureau in Magnolia, just north of Green Cove Springs on the St. Johns River. In 1866 the Freedmen’s Bureau utilized the Magnolia Hotel as a hospital and orphanage but found the roads too primitive for moving patients. Brock, who had a residence in nearby Middleburg, was hired to bring patients and supplies to the facility.

Educator and reformer Chloe Merrick Reed purchased the mansion of Confederate General Joseph Finnegan in Fernandina for just $25 at a tax auction in 1864 to use as an orphanage. She was forced to move the orphans to a new location, however, after Finnegan regained his home two years later. The children were relocated to the Magnolia Freedmen’s Bureau, likely via the Darlington. By 1868 the Magnolia Hotel was returned to its original owner, and the orphans were placed in foster homes.

Land along the St. Johns River was also promised to freedmen as part of General William T. Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15, commonly known as the “40 acres and a mule” policy. This 1865 edict was a settlement to allow emancipated individuals the opportunity to work the land until they had earned enough to pay the government the value of the property. Sadly, the order was rescinded a few months later by President Andrew Johnson after President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination.

Florida’s Golden Age of Steamboats

Florida’s Golden Age of Steamboats

Brock’s hunch about the profitability of steamboat travel up and down the St. Johns River proved prophetic, as northern tourists streamed into Jacksonville after the war and booked passage on steamers from a growing list of competitors. “During the ‘season,’ boats continually run from Jacksonville to Enterprise, and back again; the round trip being made for a moderate sum, and giving, in a very easy and comparatively inexpensive manner, as much of the peculiar scenery as mere tourists care to see,” reported Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Hubbard Hart, like Brock was also born in Vermont, transported passengers (including Stowe) up the Ocklawaha River to Silver Springs on his line of steamers. Frederick deBary, who Brock assisted in setting up his Lake Monroe estate, established his own line of first-class steamboats. But the prosperity of this age was not available to everyone.

Despite the short-term success of all-Black communities such as Garfield, racial issues still persisted in the region. Henry Sanford, whose namesake town absorbed the settlement of Mellonville on the opposite side of Lake Monroe, recruited workers from Sweden to labor in his citrus groves after “armed white vigilantes attacked the camp of Sanford’s workers.” Surviving Black workers fled, never to return, wrote author Mark Derr in Some Kind of Paradise. It is into this environment that the triumphant story of Rose emerges.

Actors from Lani Friend’s 2013 play, “A Grand Tour Upriver with Jacob Brock and Commodore Rose.”

A Portrait Beyond Stereotypes

Orlando Sentinel history columnist Jim Robison wrote that Rose’s last name eludes historians, but the “folklore lives on from the travelers” who saw and heard her speak the “final word in her every tone and gesture” during St. Johns River steamboat journeys. Ledyard Bill gives a thorough account of her physical appearance, noting that she was “a stout-built athlete of two hundred pounds of medium height, a full piercing eye, regular features, and with a particularly commanding voice.”

The positive portrayal of Rose by Stowe and Bill is unusual, in that most travel literature of the period presented Southerners – both Black and white – in pejorative descriptions, using broken dialect that reinforced ugly stereotypes. “What Stowe and Bill did,” suggests historian Joy Wallace Dickinson, “is give dignity to a person who might often be reduced to a caricature.” Lani Friend, who has done extensive research on both Rose and Brock, wrote and produced a play that examines the relationship between these two historical characters that is based on Stowe’s account of her visit to Enterprise.

Brock’s luck would run out, and he would declare bankruptcy in 1877. He died a short time later in Jacksonville. The Brock House hotel was renamed the Epworth Inn early in the 20th century, and the property would become part of the Methodist Children’s Home, an orphanage established in 1908 and still open today. Now the only steamboat operating regularly on the St. Johns is a replica that offers dinner cruises from the Port of Sanford. Brock’s legacy endures, however, in the name of one of the main streets in the unincorporated hamlet of Enterprise: Jacob Brock Avenue.

Of all the enslaved people who found freedom on the St. Johns River, Commodore Rose stands alone as perhaps the best known, yet many details of her life remain obscure. Lani Friend and the staff of the Enterprise Museum continue the search for more information. “According to writers of the time,” Friend writes, Rose was “strong, skilled at her work, [and] resilient, as anyone in her situation in life would have had to be. . . . She might have made a great CEO today, keeping a big company afloat and navigating the shoals of the modern economy. . . . She survived, endured, and transcended all.”