by Joy Wallace Dickinson

Pioneer Florida was a lot like the Wild West, so perhaps it’s fitting that an icon of the American frontier – a venerable bison named Barney – made his mark in history and rumbled into eternity on the sandy main drag of a Florida city, Orlando, long ago in 1912.

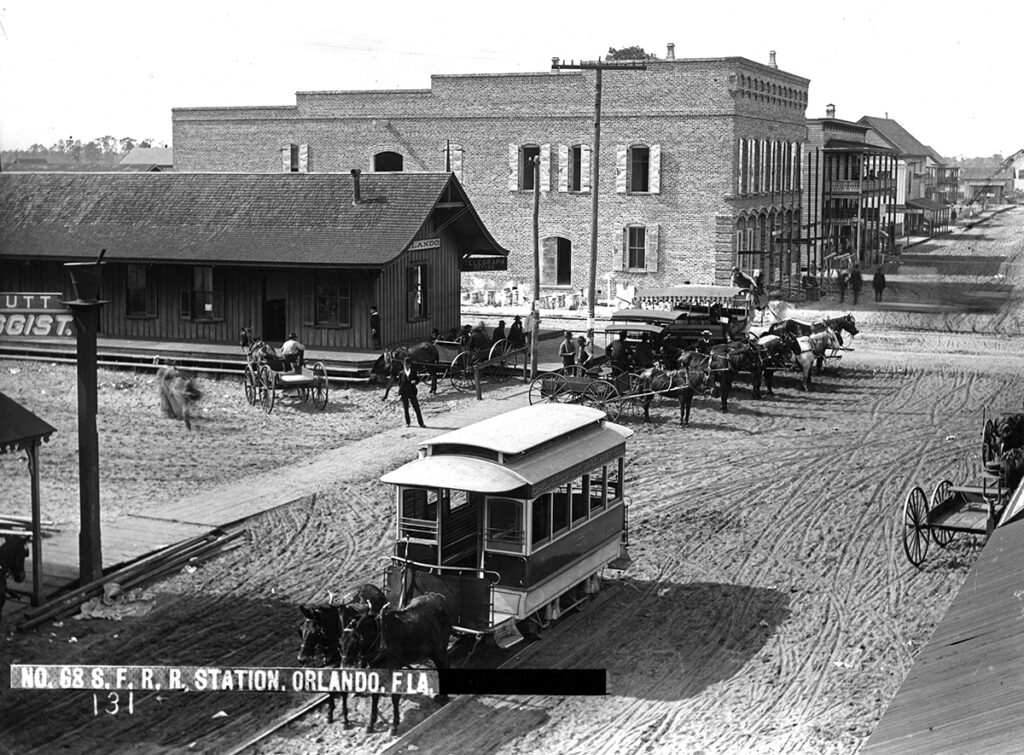

It happened on October 22, after the evening performance of Buffalo Bill Cody’s touring show, then the biggest entertainment ever seen in Orlando. In two performances, Cody’s extravaganza drew a crowd of 10,000, according to Orlando’s Daily Reporter-Star. That’s more than double the city’s population in 1912 of about 4,000 people.

American icons

Barney was one of a breed that in 1912 had nearly vanished – the largest land mammal in North America since the end of the Ice Age. Millions of Plains bison, or American buffalo, once ranged over much of North America. “No other wildlife species has had as much impact on humans and the ecosystems that they occupied than bison,” the National Park Service notes.

By the 1890s, one study estimated that only a few hundred animals remained, and in 1905 the American Bison Society was formed to help bring them back. Today about 20,500 Plains bison roam in conservation herds, with an additional 420,000 in commercial herds, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Commission.

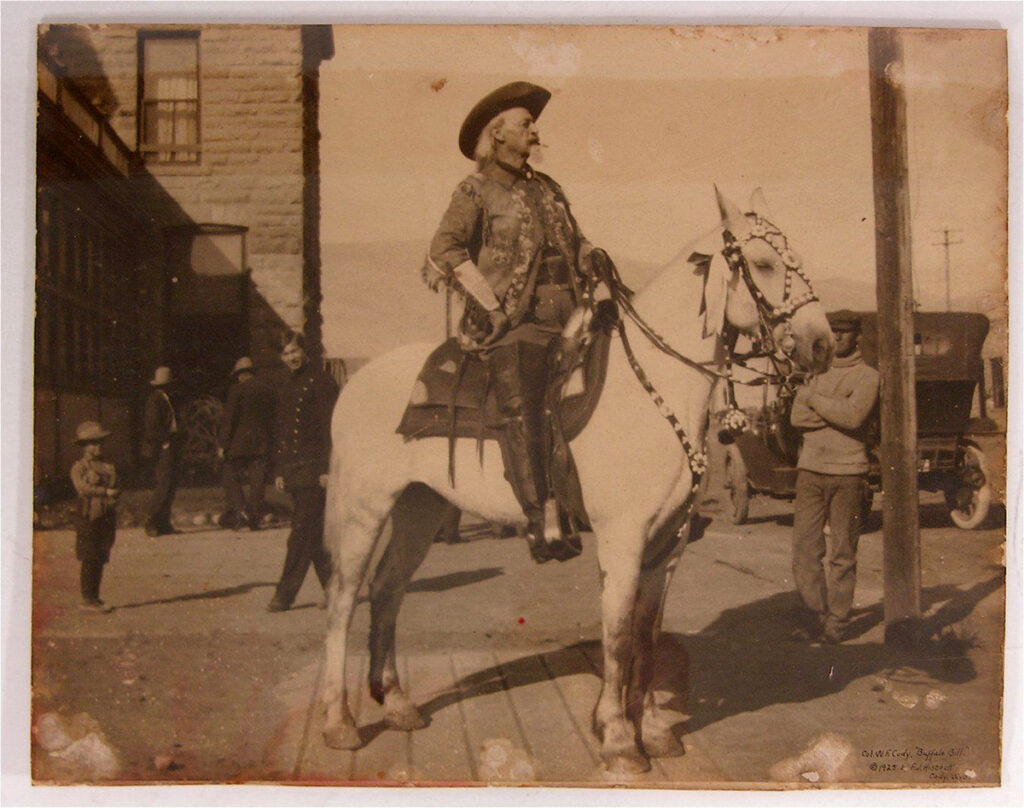

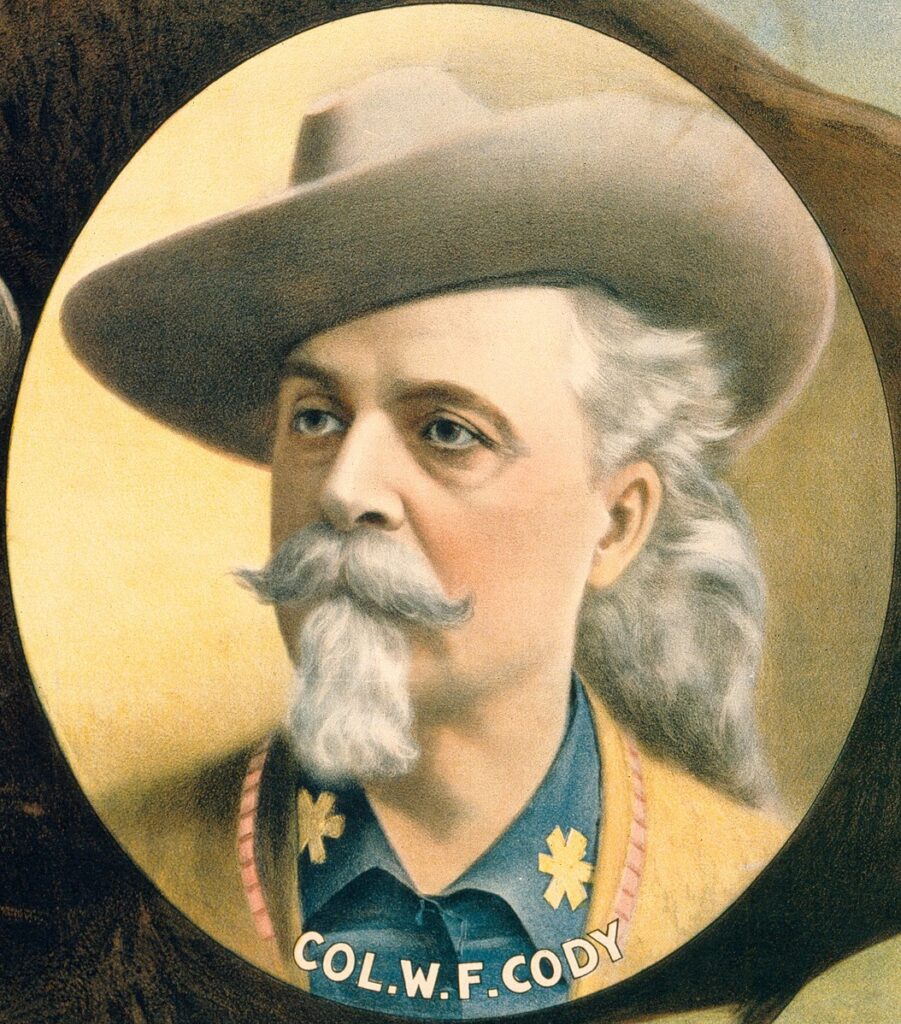

Like the bison, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and his Wild West show were also American icons. The show’s Florida stops in 1912 were advertised as part of a farewell tour by “the grand old man of the West,” although that was probably said with a wink, one Florida news story noted. The show was an extravaganza by 1912 standards – the “greatest aggregation of men and horses ever seen in Florida,” one news account noted, with three trains needed to transport its cast, tents, and animals through Florida, from Tampa to Orlando to Palatka to Jacksonville.

And, although it seems a period piece now, Buffalo Bill’s touring show may well have been the most influential saga in American entertainment, helping shape popular conceptions of the West and the “cowboy” to the present day. The shows have been credited with influencing Walt Disney in his conception for Frontierland at the original Disneyland. At Disneyland Paris, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show” pulled in thousands of spectators before it closed in 2020, decades after the original show first became the toast of the French capital in 1889.

Born in 1846 in the Iowa territory, William F. Cody had experienced many true-life aspects of the American West in his youth. “He herded cattle and worked as a driver on a wagon train, crossing the Great Plains several times,” according to the Buffalo Bill Museum. “He went on to fur trapping and gold mining, then joined the Pony Express in 1860.” After the Civil War, Cody scouted for the U.S. Army and gained the nickname “Buffalo Bill” as a hunter. While he was still in his 20s, popular dime novelist Ned Buntline turned him into a national folk hero, a fictionalized combination of Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone, and Kit Carson, and Cody lived the rest of his life between the worlds of myth and reality, one of America’s entertainment giants.

By the time he came to Orlando, Cody had toured for more than 40 years in combinations of shows that at points featured now legendary figures including “Wild Bill” Hickok, Annie Oakley, and the great Lakota leader Sitting Bull. And if Orlando news reports were right, Barney the buffalo had been with him for more than 30 of those years. Barney might even have been one of the animals Cody took with him during his tours of Europe.

Where a buffalo roamed

It was in Orlando, though, that the great buffalo’s long life ended. It happened about 10:30 p.m., after the show’s second performance at the fairgrounds on West Livingston Street. Show workers were trying to get Barney back to the show’s railroad cars, somewhere near what’s now Church Street Station. Whether it was old age or a fever that got to poor Barney, we’ll never know, but he busted loose and ran amok on Orange Avenue. Barney headed first into Kanner’s store, where a shocked Mr. Kanner was still at work, and then to Duckworth’s, where a gathering crowd worried he would break the expensive plate glass window.

With the ends of their lassos attached to their saddles, four of the show wranglers threw their ropes over him and pulled the old buffalo to “the light at the Guernsey corner” at Orange and Church, according to the Daily Reporter-Star. There, old Barney was breathing his last. The wranglers managed to get him on a cart, but he died on the way to the train, perhaps not far from the historic 1889 train station that still graces Church Street. At Palatka, the show’s next stop, his hide would be made into a rug, maybe worth as much as $300, the Reporter-Star’s unnamed writer noted. “So it happened,” the story concluded, that Orlando had a place in “an incident of the passing of the Old West.”

Church Street in Orlando, 1882, courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

Barney art box

In 2024, the History Center was fortunate to collaborate with the City District on their Art Box Program. The project showcases the talents of local artists who painted traffic boxes throughout the district, turning these everyday structures into works of art that brighten our urban landscape. In our case, that also means providing a history lesson through the talents of artist Kelly Williams-Cramer. On a traffic box located near the intersection of South Street and Orange Avenue, about a block from where he met his fate, Kelly’s art pays homage to dear Barney.