By Lesleyanne Drake, from the Winter 2018 edition of Reflections Magazine

(Warning: some explicit language contained within direct quotations)

It was a warm, spring day in 1982 when backhoe operator Steve Vanderjagt paused to examine a pale rock he had uncovered while working construction near the edge of a pond at Windover Farms in Brevard County, Florida. Turning the object over in his hands, Vanderjagt saw two eye sockets and realized he was holding a human skull. His first thought was, “Oh shit!”

What Vanderjagt did not know at the time was that he had stumbled across a prehistoric cemetery that would prove to be one of the most amazing archaeological discoveries of the 20th century.

Developers Jack Eckerd (son of the famous drugstore founder) and his stepson Jim Swann had planned for Windover Farms to become a housing development serving the growing community of Titusville. To help draw people to the area, Swann built a restaurant called the Roost, with a small lunch counter and offices on the second floor. Swann was working at the Roost when Vanderjagt walked in carrying a bucket of the bone remains. Not knowing whom to contact, Swann walked the remains over to a nearby Florida Highway Patrol station.

“According to Swann,” archaeologist Rachel Wentz later wrote in her book Life and Death at Windover, “they were met with a chilly reception. The troopers took one look at the skeletons and said, ‘We only do car wrecks.’ ”

After an examination by the county coroner showed the bones were not the remains of modern humans and, thus, of little value to law enforcement, Swann had to fight for them to be returned to him. When he did get them back, the remains resided in Swann’s garage, then in the tiny trailer on the Windover Farms construction site, where workers repeatedly stubbed their toes on the large containers. But Swann was intrigued by what else might be hidden beneath the layers of pond muck, and that would have remained a mystery if not for Swann’s next decision – to call in archaeologist Glen Doran.

Doran was a young, up-and-coming professor at Florida State University in Tallahassee, and although he was not the first archaeologist to visit Windover, he was the first to recognize the site’s potential and not be daunted by the challenges it presented.

He was immediately fascinated by the age of the remains – heavy wear on the teeth provided evidence of a prehistoric diet – but he didn’t have the funds to have them radiocarbon dated. Swann volunteered the money, and when the results of the testing came back, both men were astounded. The bones were over 7,000 years old – more than 2,000 years older than the Egyptian pyramids.

Archaeologist Dave Dickel “pedestalling” a burial (working the muck away from a bone until it is entirely exposed in place) before it is mapped, photographed, and removed. Photo courtesy of R. Brunck.

WET-SITE ARCHAEOLOGY

Wet sites have yielded some of the most spectacular archaeological finds in the world. Prior to Windover’s discovery, ancient human remains had been uncovered at four others in Florida: Little Salt Springs (Sarasota County), Warm Mineral Springs (Sarasota County), Republic Groves (Hardee County), and Bay West (Collier County). Known as mortuary ponds, these sites served as cemeteries during the Early and Middle Archaic periods, roughly 10,000 to 5,000 years ago.

These burials were preserved because of the remarkable properties of the substance in which they were sub-merged – peat. Made up of layer upon layer of decomposing organic materials (mainly vegetation), peat provided an oxygen- and acid-free environment that allowed bones and artifacts to survive for thousands of years. However, as soon as the materials are excavated and exposed to the air, they begin decomposing rapidly. This is one of the many factors that make wet-site archaeology especially slow, expensive, and challenging.

Doran recruited an old friend from college, archaeologist Dave Dickel. They designed a demucking system that would remove enough water to excavate, but not too much. It was essential that the peat stay moist to protect the materials buried within. Over the course of three field seasons, in 1984, 1985, and 1986, Doran and Dickel perfected the process. They in-stalled 158 well points around the edge of the pond to capture water from both the top and bottom of the pond and eject it away from the site, creating an excavation area about the size of an Olympic swimming pool.

Digging in peat was not like digging in soil. The peat had a clay-like consistency that had to be sliced using sharpened trowels and shovels. Thin layers were slowly shaved away until the peat changed color, a sign that archaeologists were nearing a burial. Then wooden tools were used to gently scrape the muck away from the remains. Chopsticks that the archaeologists hoarded from nearby Chinese restaurants worked best. However, their most important tool was water. Bones can crack if they dry out too quickly, so archaeologists used spray bottles of water to keep the bones wet and to help remove adhered peat.

Archaeologists adapted their excavation strategy to the unique challenges of digging in dense peat. Photo courtesy of R. Brunck.

Toward the end of the first field season, Doran and Dickel made an astonishing discovery: a mushy, greasy, tan substance inside one of the skulls. Speculating on what the material might be, Doran joked that maybe it was only “snail poop.” But doctors at the University of Florida’s Shands Medical Center soon confirmed that a sample was actually human brain tissue. By the end of that year, several intact brains had been recovered. Though shrunken to a quarter of their original size, they still retained the shape and surface features of a typical human brain. According to Wentz, an editorial in a local paper ran the headline, “Brains finally discovered in Titusville!”

Though these were not the first ancient skulls found with preserved brain matter, this was the first time such a discovery coincided with advances in technology that would allow researchers to analyze the tissue on a molecular level. To ensure the preservation of the brain matter for future study, it was removed from the skulls in the field, sealed in nitrogen-filled containers at minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit and transferred to the lab at the University of Florida, where the containers were frozen at minus 94 degrees. By comparing the DNA in these tissues with the genetic sequences of other populations – particularly mitochondrial DNA (passed down maternally) and Y-chromosome DNA (passed down paternally) – it is possible to trace the history of human migration.

While researchers have determined that DNA did survive in the brain tissue, the samples are still extremely fragile. Instead, an analysis of DNA extracted from the skeletal remains has yielded the most interesting results. Conducted decades after the excavation, the study revealed that the people buried at Windover migrated to North America from Asia but do not seem to be related to any living Native American tribes or to any known prehistoric peoples. This leaves one of two possibilities: either their descendants died out, or their population bottle-necked (was reduced sharply) before the genetic markers we find in modern humans evolved.

WHAT CAN WINDOVER TELL US?

Despite the remarkable discovery of the intact brain matter, Doran and Dickel were initially disappointed by the results of their excavation. The finds uncovered during the first two field seasons in 1984 and 1985 were either too commingled or too isolated to draw many conclusions. But during the third and final field season in 1986, as the team began digging in the northern part of the pond, they suddenly started finding undisturbed burials with distinct, nearly complete skeletons. This, Wentz writes, is when “the graves began to speak.”

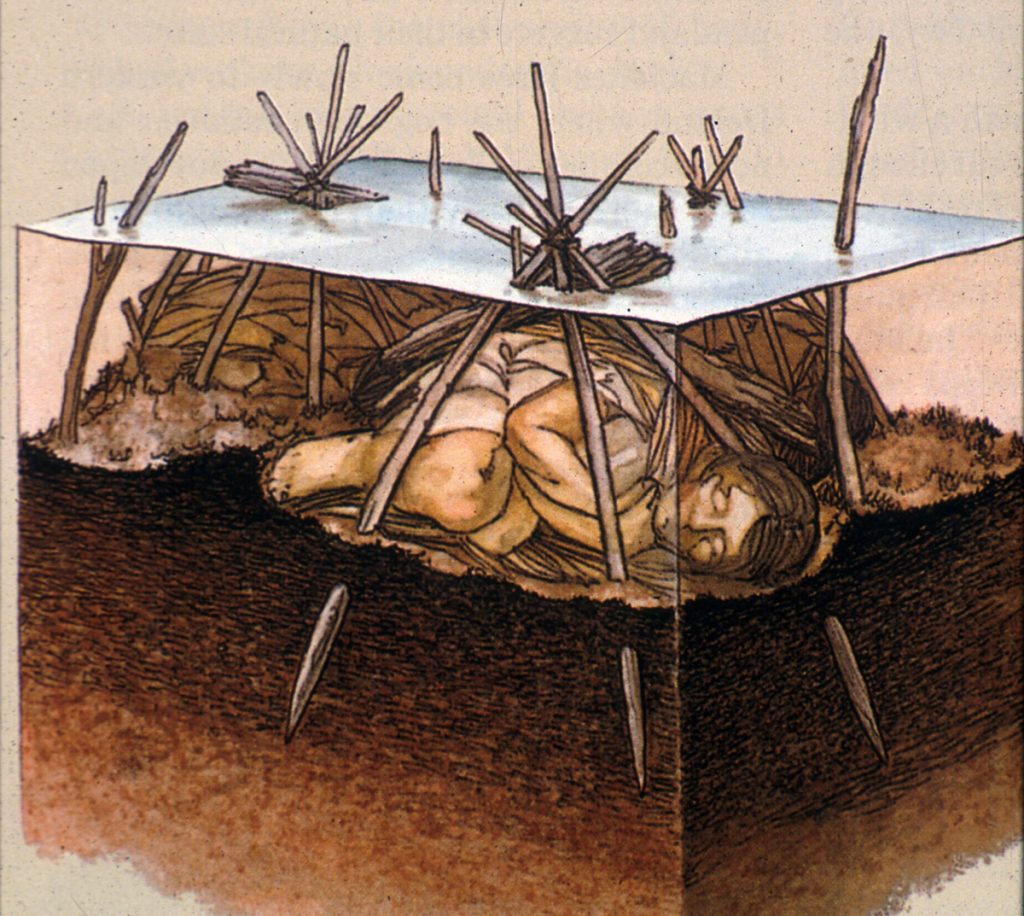

The story they tell begins 9,000 years ago when ancient humans began using Windover as a cemetery. As the indigenous people moved through the area seasonally, they would bury their dead in the pond during late summer and early fall. We do not know where they lived the rest of the year, but we can tell from the level of decomposition that the bodies were interred within 48 hours after death, so they were probably living nearby during the autumn months. The bodies were tucked into a “flexed” position, bundled in fabric along with a variety of grave goods, and submerged beneath the water, typically on their left sides, facing west. Wooden stakes driven through the cloth kept them anchored to the bottom of the pond. Generation after generation returned to the pond to bury their dead in this manner for the next 1,000 years.

Life in prehistoric Florida was not easy. The bones at Windover show signs of numerous ailments, including disease, broken bones, and malnutrition. About half of the individuals died before the age of 18, and many more did not live past their late forties. By that time, the high level of grit in their diet (caused by using stone tools and surfaces to prepare food), combined with the use of their teeth as tools, had worn their teeth down to nubs. Arthritis and abscesses were common. It makes sense, then, that several were found with large quantities of plant seeds known to have pain-relieving properties in their stomach region, potentially representing the first archaeological evidence of the medicinal use of plants.

The people of Windover probably also splinted broken bones, performed amputations, and cared for their sick and elderly. Only one skeleton showed signs of violence: a young man with an antler tine embedded in his hip – and a missing skull.

The artifacts buried with the bodies can tell us just as much as the remains themselves. In addition to a variety of wooden artifacts, archaeologists recovered 119 objects made from animal parts, many of which would have been used as tools to fish, hunt, and butcher meat. Deer antler was used to make projectile points and barbed fishing hooks. Scrapers and other tools were made from the teeth of sharks, opossums, and canids (mammals in the dog family). Containers made of turtle shell, too small for use in cooking food, were possibly used to prepare medicinal plants.

In one burial, archaeologists also found a bottle gourd that may have been used as a container. The oldest-known example of a bottle gourd north of Mexico, this find may support the theory that some of the earliest cultivated plants in the New World were not sources of food, but utilitarian plants that provided light, durable containers, and tools. Though very few stone artifacts were found, the points that were recovered can be traced to quarries in Sumter County, more than 80 miles away.

In addition, awls, perforators, punches, and pins made from animal bones and antler would have been used in the preparation of hides, baskets, cordage, clothing, and other fabrics. Remarkably, 87 fragments of these handwoven, palm-fiber textiles survived. Extremely fragile and nearly indistinguishable from the surrounding peat, the cloth had to be removed with the entire burial in a single, large block and transported back to the laboratory where specialists in preserving ancient fiber worked to carefully extract and conserve them. Although their production and use certainly predate Windover, these woven textiles represent the oldest surviving examples of this type in the New World.

Not all of the grave goods had a utilitarian purpose. Three necklaces adorned the neck of a woman in her early twenties, each made from a different material – fish vertebrae, Sabal palm seeds, and shells. Two more were found draped over a 2-year-old.

An artist’s rendering of a cutaway of Windover pond shows how the burials were originally positioned. Image courtesy of G. Doran.

LEGACY

Garnering international fame, the archaeological finds at Windover were greeted by public demand for information so overwhelming that Doran was forced to hire a full-time communications specialist to respond to media inquiries, organize volunteers, and spearhead educational initiatives such as tours and school programs. The Brevard Artists’ Association even held a contest, challenging artists to produce the best Windover-inspired artwork, with Dickel, much to his dismay, to serve as the judge.

By the end of the third field season, Doran, Dickel, and their team had uncovered a minimum of 168 skeletons, including 91 with preserved brain tissue. It is the largest, most demographically diverse skeletal discovery from this time period in the New World, with ages ranging from newborn to over 65, and both sexes equally present.

Such a broad, well-preserved sample has allowed archaeologists to learn about prehistoric burial practices, lifeways, health, migration, and much more, and the materials will continue to be studied for years to come as new technologies open up fresh avenues for research.

Windover may also be one of the last prehistoric cemeteries ever excavated in the United States because, several years later, federal and state laws were passed that protect indigenous human remains, funerary items, and sacred objects – a response to the long history of stripping Native Americans of their material culture.

Although excavations of wet sites are notoriously challenging, a convergence of timing, technology, funding, and interest made the Windover excavation feasible. As Doran wrote in his 2002 anthology about the site, “Our investigations at Windover were a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. . . . Never in my wildest dreams would I have been so bold as to envision excavations of a site like this. It was phenomenal. Being in the right place at the right time, and not knowing excavation of such sites was considered to be both unproductive and essentially impossible, has certainly made me one of the luckiest archaeologists of all time.”

There are almost certainly other Windovers in Florida, Doran claims. But whether or not another site will ever offer up so many of its secrets still remains to be seen.

Join Dr. Rachel Wentz, author of Life and Death at Windover, as she explores the discovery and excavation of Windover on Sunday, January 24, 2021, at 2 p.m.