The J. Brailey Odham Collection at the Orange County Regional History Center

The J. Brailey Odham Collection at the Orange County Regional History Center

By Cynthia Cardona Meléndez from the Fall 2006 edition of Reflections From Central Florida

The political scene in Florida in the 1940s and 1950s exhibited great transitions and, simultaneously, resistance to these changes. Traditionally Democratic, the state was undergoing “New South” advancements but by no means were “Old South” ideals on the decline. Florida’s economy during the 1940s and 1950s was doing well in part due to the success of agricultural crops such as citrus and improvements in infrastructure, but the state was still plagued with racism and racist politicians who were unwilling to accept the social changes desperately needed in Florida. James Brailey Odham, an idealistic young businessman from Sanford, embraced the challenges associated with progress and change when he decided in 1947 to run for the Florida House of Representatives.

Odham was born in 1919 in Brunswick, Georgia, grew up in Sanford, and attended Louisiana College where he majored in history and business administration. After college, Odham joined the U.S. Navy in 1942 and served as a junior officer on the ammunition ship USS Nitro during World War II. After three years in the military, Odham returned home to Sanford and ran his father’s Gulf Oil Corporation distributorship. In 1947, he burst onto the public scene when he was elected to the Florida House to represent Seminole County.

Upon his entrance into the race for the state legislature, Odham remarked, “I feel our state and county are embarking upon the most eventful era in our history, and now, more than ever before, there is a great need for a government operated cleanly and wisely.” Odham would have to hold true to his pledge to clean up Florida’s government when shortly after his win he claimed he was offered a bribe of $500 by Bernie Papy of Monroe County to vote against a “bookie bill” that would have prohibited telegraph and telephone service from transmitting race results to bookmakers. The allegations against Papy went before a jury trial and he was eventually acquitted, but Odham had succeeded in representing sound government while simultaneously attracting the attention of the media and public.

After two terms in the Legislature, Odham, who was 32 years old at the time, decided to run for governor in 1951, making him the youngest candidate to run for the state’s highest office. Proclaiming that he wanted to curtail the corrupting practices of the entrenched elites in Florida’s political system, Odham also vowed to be tough on gambling racketeers and create equal opportunity for everyone in Florida regardless of race. With his platform in place, Odham implemented a unique campaign strategy that gave him an edge with the media and a unique place in Florida political history.

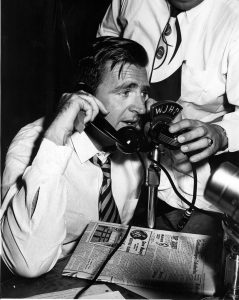

In order to reach a larger number of voters during his campaign, Odham began hosting what became known as talkathons across the state in which he could be heard on the radio for 24-hour marathons. During a typical talkathon, Odham invited civic groups, churches, labor unions, and individual voters to call in and ask him questions, giving his campaign an air of spontaneity. Additionally, talkathons would also attract voters to the host establishment to watch Odham speak, doubling his questions and, more importantly, his exposure. By the end of Odham’s campaign, he had held more than a dozen talkathons, answering more than a thousand questions in just a single session.

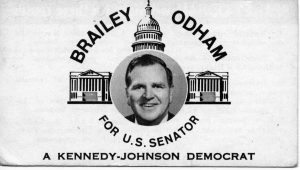

Although his campaign strategy was unique, Odham lost the election to Dan McCarty, who died in office nine months later of a heart attack, giving Odham a second opportunity to run for governor in 1954. In this election, Odham used a scaled-down version of his talkathon strategy consisting of less time on the air, but he again lost the race for governor, this time to LeRoy Collins. Odham went on to serve the public in 1958 as chairman of the Florida Milk Commission, leading the fight to eliminate price-fixing in the dairy industry. In 1960, Odham became a delegate to the Democratic National Convention and served as state finance chairman for the Kennedy-Johnson ticket while simultaneously becoming a home builder in Sanford and opening Florida Care, Inc., at the time, one of Florida’s largest and most advanced nursing homes. Odham decided to run for public office one last time in 1964, running for U.S. Senate as a “Kennedy-Johnson Democrat” by promoting Medicare, minimum wage, and civil rights legislation. This was in direct contrast to his “Old South” opponent, former governor Spessard Holland of Polk County, the Democratic incumbent who had been serving in the Senate since 1946. Odham lost the Democratic primary election to Holland who went on to win the Senate seat. Returning to real estate development in Sanford, Odham also served as the chair of the Orange County Office of Economic Opportunity in 1967 and briefly returned to politics with his support of Edmund Muskie’s 1972 presidential campaign. Odham died in 1996.

In 1997, Odham’s widow, Louise Odham, donated to the Orange County Regional History Center what is now known as the J. Brailey Odham Collection. Within the collection, there are news clippings compiled by the Florida Clipping Service in Tampa, which chronicle Odham’s terms in the Legislature, his bids for governor, and his term as chairman of the Milk Commission. The collection also consists of scrapbooks, letters written to Odham by John and Robert Kennedy, meeting transcripts from various committees that Odham served on, Florida election totals by county for the governor’s races of 1952 and 1954, and certificates and awards awarded to Odham during his years of service. Of particular interest in this collection are the various types of campaign literature created for both of Odham’s gubernatorial races touting him as “The Man Who Can’t Be Bought, Bossed, or Bluffed” and a small group of photographs, some of which provide a comical view of Odham leering at a clock indicating he had only completed nine of his 24 talkathon hours.

The J. Brailey Odham Collection documents Odham’s commitment to the implementation of change in Florida’s political system and his commitment to the continued modernization of the state. By calling for honesty and hard work among his political peers, Odham was able to help push Florida toward a new era of growth, prosperity, and equal treatment under the law for all.